Notes on the Program by DR

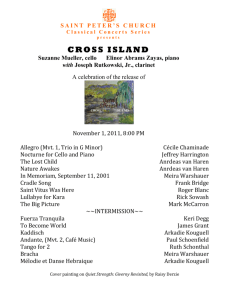

advertisement

Notes on the Program Trio in A major for Piano, Violin, and Cello, Hob. XV:18 Franz Joseph Haydn Born March 31, 1732 in Rohrau, Lower Austria. Died May 31, 1809 in Vienna. Composed in 1794. Duration: 15 minutes The Trio in A major (XV:18 in Hoboken’s catalog; H.C. Robbins Landon places it as No. 32 in his chronological listing of the trios) was composed during Haydn’s second London visit in 1794. The piece was one of three such works (Nos. 32-34; H. XV:18-20) written for publication by the local firm of Longman and Broderip; the set was registered at Stationers Hall on November 17, 1794. The works were dedicated to Princess Marie Hermenegild Esterházy, the wife of Prince Nikolaus II and one of the more recent additions to the family that employed Haydn for nearly a half century. Between 1796 and 1802, Haydn wrote six superb Masses for the annual celebrations at the Bergkirche in Eisenstadt of the Princess’ nameday. She seems to have been fond of the family’s old music master, and did what she could to make his last years in Vienna comfortable. As was typical of the 18th-century genre, Haydn’s A major Piano Trio entrusts most of the musical argument to the keyboard, with the strings often relegated to augmenting and doubling roles. Though the piece was written for the growing market of British and Continental musical amateurs, the music exhibits a mastery of form and style and a breadth of expression reminiscent of the peerless symphonies that Haydn devised for his London concerts. The work opens with a genial sonata-form movement that is built almost entirely from the angular but smoothly flowing motive given in imitation at the outset by the piano. The Andante juxtaposes melancholy and contented strains in a three-part form (A–B–A). The movement ends on an inconclusive harmony to lead directly to the finale, a jokey rondo of Gypsy persuasion. Trio for Violin, Viola, and Cello Jean Françaix Born May 23, 1912 in Le Mans. Died September 25, 1997 in Paris. Composed in 1933. Duration: 13 minutes Jean Françaix, the French composer, pianist and advocate of Debussy’s artistic philosophy of “faire plaisir” (“giving pleasure”), was born into a musical family in Le Mans in May 1912 — his father was a pianist and composer and director of the Le Mans Conservatory; his mother taught voice and founded a local chorus. Jean received his earliest training from his parents but he showed such precocious talent that he was regularly commuting to Paris for private lessons at the Conservatoire by age nine. He was much upset by news of the death of Camille Saint-Saëns in that year (1921), and vowed to his father that he would “take his place” as a musicien français; Françaix’s earliest published work, a suite for piano, appeared the next year. He settled in Paris a few years later for regular study at the Conservatoire, where his tutelage was entrusted to Isidor Philipp for piano and Nadia Boulanger for composition. Françaix won the Conservatoire’s first prize in piano when he was just eighteen, and two years later he gained recognition as a composer with a symphony that was premiered in Paris by Pierre Monteux in November 1932. He played the first performance of his Concertino for Piano and Orchestra with much success in 1934, and came to international prominence when he presented the work at a festival of contemporary music in Baden-Baden two years later. He subsequently made numerous tours throughout Europe and the United States as composer and pianist. The 1933 ballet Scuola di ballo, choreographed by Léonide Massine for the Ballets Russes de Monte Carlo, marked Françaix’s entry into the genres of musical theater, for which he produced five operas, sixteen ballets, and many film scores before his death in Paris on September 25, 1997. His large output also includes some four-dozen orchestral pieces (many calling for one or more solo instruments), numerous chamber works (for which he favored wind instruments), songs, an oratorio (L’apocalypse de St. Jean), and a considerable amount of music for accompanied chorus. American musicologist David Ewen wrote of the idiom that characterized Françaix’s works throughout his life: “In his music, Françaix is as Gallic as his name. Lightness of touch, effervescence of spirit, irony that sometimes approaches malice, briskness of movement — the vein so many French composers adopt with such skill — are found in all of Françaix’s major works. He was greatly influenced by the neo-classical manner of Stravinsky, to a point where slender form, conciseness, brevity, simplicity, and clarity of writing become almost a fetish. But there is enough acidity in the harmony and robustness in the rhythm to give his music contemporary spice.” Françaix’s Trio for Strings, from 1933, opens with an agile movement based on a brittle theme that returns frequently enough to suggest the form of a rondo. The sparkling Scherzo is witty and insouciant; the central trio is delightfully oafish with its missed entrances and dropped beats. The slow, plaintive song of the third movement serves as an expressive foil for the energy of the surrounding music. A zesty rondo built on a fanfare motive closes the Trio. Quartet in E-flat major for Piano, Violin, Viola, and Cello, Op. 87 Antonín Dvořák Born September 8, 1841 in Nelahozeves, Bohemia. Died May 1, 1904 in Prague. Composed in 1889. Premiered on November 23, 1890 in Prague by Hanus Trnecek (piano), Ferdinand Lachner (violin), Petr Mares (viola), and Hanus Wihan (cello). Duration: 35 minutes By the time that Dvořák undertook his Piano Quartet in E-flat major in 1889, when he was nearing the age of 50, he had risen from his humble and nearly impoverished beginnings to become one of the most respected musicians in his native Bohemia and throughout Europe and America. He was invited to become Professor of Composition at the Prague Conservatory at the beginning of the year, but refused the offer after much careful thought in order to continue devoting himself to creative work and touring as a conductor of his music. In February, his opera The Jacobin enjoyed a great success at its premiere in Prague, and the following month his orchestral concert in Dresden received splendid acclaim. In May, the Emperor Franz Josef awarded him the distinguished Austrian Iron Cross, and a few months later, he received an honorary doctorate from Cambridge University. Dvořák composed his Second Piano Quartet at his country home in Vysoká during the summer of 1889, the time between receiving these last two honors, in response to repeated requests from his publisher in Berlin, Fritz Simrock, who had been badgering him for at least four years to provide a successor to the Piano Quartet, Op. 23 of 1875. The new composition was begun on July 10th, and completed quickly within five weeks, evidence of the composer’s testimony to his friend Alois Göbl that his head was so full of ideas during that time that he regretted he could not write them down fast enough; he completed his boundlessly lyrical Symphony No. 8 just two months later. Simrock published the score of the Quartet early in 1890, and the premiere was given in Prague by Hanus Trnecek (piano), Ferdinand Lachner (violin), Petr Mares (viola), and Hanus Wihan (cello) in November of that year. The Quartet’s first movement follows a freely conceived sonata form. To launch the work, the unison strings present the bold main theme, which immediately elicits a capricious response from the piano. Following a grand restatement of the opening theme by the assembled forces and a transition based on a jaunty rhythmic motive, the viola introduces the arching subsidiary subject. The intricately worked development section is announced by a recall of the theme that began the movement. A varied recapitulation of the earlier materials rounds out the movement. “The Lento,” wrote Otakar Sourek in his study of the composer’s chamber works, “is among the loveliest slow movements in thought-content and the most deeply moving in mood that Dvořák created.” This movement is unusual in its structure, consisting of a large musical chapter comprising five distinct thematic entities played twice. The cello presents the first melody, a lyrical phrase that Sourek believed was “an expression of deep, undisturbed peace.” The delicate second motive, given in a leisurely, unruffled manner by the violin, is even more beatific in mood. A sense of agitation is injected into the music by the animated third theme, entrusted to the piano, and rises to a peak of intensity with the stormy fourth strain, which is argued by the entire ensemble. Calm is restored by the piano’s closing melody. This thematic succession is repeated with only minor changes before the movement is brought to a quiet and touching end. The third movement, the Quartet’s scherzo, contrasts waltz-like outer sections with a central trio reminiscent of a fiery Middle Eastern dance. The finale, like the opening Allegro, follows a fully realized sonata form in which an energetic main theme (which stubbornly maintains its unsettled minor tonality for much of the movement) is contrasted with a lyrically inspired second subject, first allotted to the cello. A rousing coda of almost symphonic breadth closes this handsome work of Dvořák’s maturity. ©2011 Dr. Richard E. Rodda