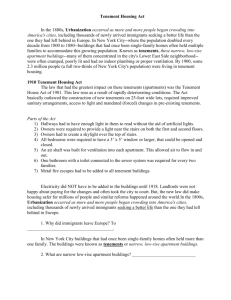

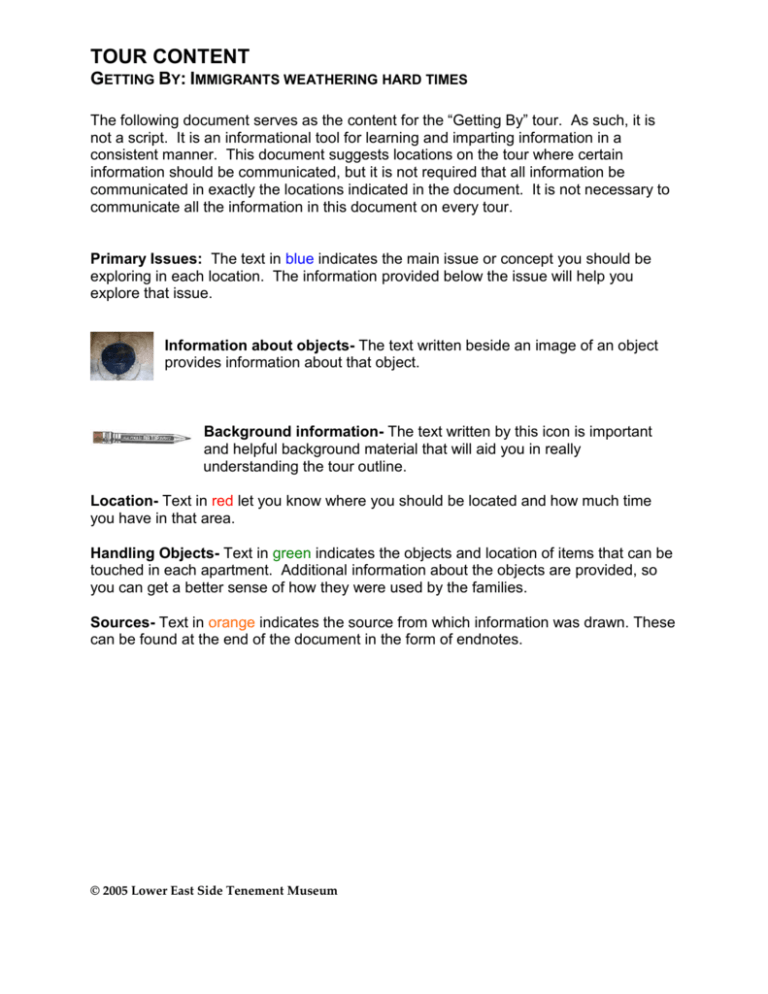

tour outline - Lower East Side Tenement Museum

advertisement