Word - Department of Computer Science and Engineering

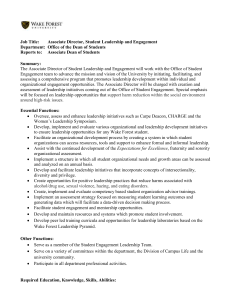

advertisement