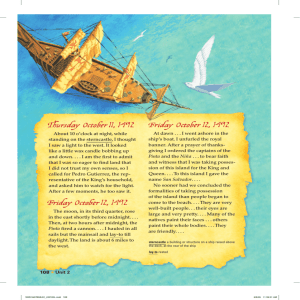

Leon's Antarctic Journal

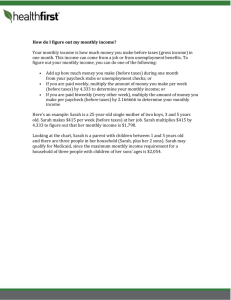

advertisement