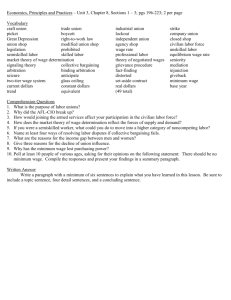

Word Doc.

advertisement

Raise the Minimum Wage. Farrell, Chris, Business Week Online, 10/19/2006, p. 5 Database: Academic Search Premier Abstract: The article focuses on the minimum wage in the U.S. Several economists, including Kenneth Arrow, Clive Granger, Lawrence Klein, Robert Solow, and Joseph Stiglitz, called for in a petition to raise the minimum wage, put together by the Economic Policy Institute in Washington. The economists are requesting the U.S. Congress for wage floor raise because the minimum wage was still $5.15 an hour since 1997. Raise the Minimum Wage SOUND MONEY It's the least that can -- and should -- be done for low-income workers. But it still won't be enough to restore purchasing power Congress, raise the minimum wage. That's what 664 economists -- including Nobel laureates Kenneth Arrow, Clive Granger, Lawrence Klein, Robert Solow, and Joseph Stiglitz -- called for in a petition put together by the Economic Policy Institute, a liberal think tank based in Washington. And they're right. After all, the current wage floor is $5.15 an hour -- and that's where it has been since 1997. And inflation has eroded the purchasing power of the minimum by some 20%. The economists want the wage floor raised a relatively modest amount over several years -- to $7.25 an hour. The economists are also suggesting that the minimum wage be indexed to inflation. The traditional rejoinder to any suggestion for a higher minimum wage has been that it kills off low-income jobs. Indeed. economists have long held that the minimum wage is a classic case of good intentions and bad outcome. A 1990 survey of 1,000 economists found that some 63% agreed with the statement that minimum wages increase unemployment among young and unskilled workers. On his Cafe Hayek blog, George Mason University economist Richard Russell expresses disgust with hundreds of his petitionsigning peers. In a post titled "Hall of Shame" Russell asks, "How can you sign your name to something like that and call yourself an economist?" SHIFTING OPINION The truth is, economists are increasingly divided about the employment impact of a wage floor. For instance, in a 2000 follow-up to the 1990 survey, Weber State University economists Dan Fuller and Doris Geide-Stevenson learned that only 45% of those surveyed agreed that there was a nefarious trade-off between the minimum wage and jobs. That's a big shift in professional opinion in a mere decade. The turning point came with a 1994 paper by economists David Card and Alan Krueger, "Minimum Wages and Employment: A Case Study of the Fast-Food Industry in New Jersey and Pennsylvania." The economists found that employment actually rose in the New Jersey fastfood restaurants they surveyed after the state hiked its higher minimum wage; fast-food employment declined somewhat in Pennsylvania, which kept its minimum wage unchanged. Over the years a cottage industry of empirical and theoretical literature has emerged, some challenging and others reinforcing the employment perspective of the Card-Krueger results. That's all to the good. Economic progress comes from empirical studies like these. Now, although I'm no expert, my sense from the economic literature and commentary is that the job impact from a modest increase in the minimum wage is negligible to minor -- even among teens, the most vulnerable group. LONG-RUNNING DEBATE To be sure, an increase from $5.15 to $7.25 is a 40% jump. But I don't see much, if any, fallout with the increase phased in over the next three years [assuming that's the plan Congress finally backs. Certainly, it's the one on the table]. And even at that higher $7.25 rate, the minimum wage would be still well below its 1968 peak of $9.31 [in 2006 dollars]. Basically, the increase restores the buying power of low-income employees. Brad Delong, economist at the University of California at Berkeley, has thoughtfully emphasized that the key idea when thinking about the effect of the minimum wage is balance. The $7.25 goal meets that standard. The federal government has been debating the concept of raising the minimum wage for years, and in a Republican-dominated Congress it hasn't gotten many votes. [A three-year, phased-in increase in the minimum wage to $7.25 was attached in the late summer to a bill that eliminated the estate tax. It went nowhere.] Meanwhile, 22 states and the District of Columbia haven't waited on Congress and the Administration: They've already raised their minimums. And on Nov. 7, Election Day, voters in Arizona, Colorado, Missouri, Montana, Nevada, and Ohio will vote on whether to hike their state's minimum wage, according to the Economic Policy Institute. Still, the real complaint about the minimum wage is that it won't do much to improve the earnings of low-wage workers. That's why raising the minimum wage a modest amount should be coupled with improving the earned-income tax credit [EITC], the nation's most successful and largest anti-poverty program for working families. For instance, the EITC is credited with increasing the labor force participation rate of single mothers with children following welfare reform. And it lifts more children out of poverty than any other government program, according to research by economists Nada Eissa of Georgetown University and Hilary Hoynes of the University of California at Davis. LEFT BEHIND President Ronald Reagan got it right when he hailed the EITC -- now a 31year-old program -- the "best anti-poverty, the best pro-family, the best jobcreation measure to come out of Congress." But the EITC can be streamlined and made better. For instance, it's a complicated credit, with numerous and often confusing eligibility requirements. It also could be made somewhat more generous. That said, the traditional bipartisan support of the EITC has been sadly eroded, with Congressional Republicans more concerned about fraud and abuse in the EITC than with making it an even better anti-poverty program. Look, low-income workers have been left behind during the past several years. That's why an increase in the minimum wage gets a sympathetic hearing in many parts of the country, and not just in union-dominated cities or counties. Polls show that a majority of Americans favor raising it. Even in many so-called Red States there is a sense that the bottom of the income spectrum deserves improved rewards to work after all these years. And it's difficult to get policymakers to put aside their partisan differences to work toward a new, enhanced EITC. This is one of those times when what is realistically possible has to take precedence over what might be more desirable. Put it this way: One wage increase in almost nine years isn't too much to ask, is it?