The Fiscal Basis of Social, Worker and Corporate

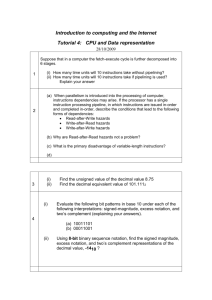

advertisement