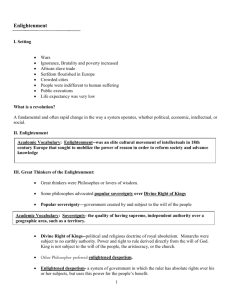

Enlightenment

advertisement

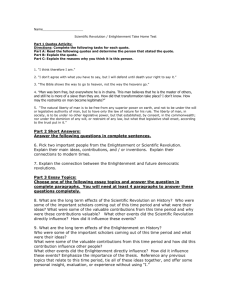

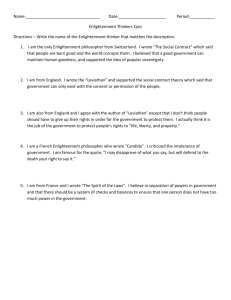

Enlightenment. Britain and the Creation of the Modern World Roy Porter (London, Penguin, 2000) Outline notes to Introduction and Chapter 1 Introduction Preliminaries Terms ‘early/first Enlightenment”: pre-1750 ‘late/second Enlightenment: post-1750 ‘long 18th c.”: entire span from Restoration to Regency [Restoration of monarchy under Charles II in 1660; Restoration period = c. 1660-1700] [Regency Act of 1811 named prince of Wales ‘prince regent’, after onset of illness of George III] ‘Georgian’: usually refers to period of George III’s reign (1738-1820) ‘Hanoverian’: period begins with reign of George I (1714) and ends in 1901 with the death of Victoria ‘The Enlightenment’/ ‘Enlightenment’/ ‘enlightenment’/ ‘enlightenments’ ‘Men’: (gendered language) ‘men of letters’, ‘man of mode’, ‘the common man’, ‘mankind’, etc “…the people they actually envisaged as doing the teaching and preaching, writing and enlightening, were male. They did not think much of women in such public contexts, and when they did, they singled them out specifically. This silently gendered language reflected a man’s world as defined by dominant male-élites…” (p. xviii) Act of Unions (1707): united parliaments of England and Scotland, creating Great Britain Second Act of Union (1801): incorporated Ireland into the United Kingdom Author’s stance (“a word on where I stand”, p. xx) Progressives: praise the philosophes (for Rights of Man); trace lineage from them to American Republic (“Europe dreamed the Enlightenment and America made that dream come true”, p. xx) Right-wing scholars: blame Enlightenment for handing the Terror its ideological ammunition; blame Rousseau’s doctrine of general will for ‘totalitarian democracy’, sanctioning fascism, Nazism and Stalinism. “After the Second World War, ‘totalitarian’ became the epithet for an Enlightenment whose managerial rationality was alleged to have imposed an ‘administered life’ which inexorably reduced society to ‘a universal concentration camp’, p. xx) Postmodern views: for Foucault: “despite its rhetoric, the true logic of the Enlightenment was to control and dominate rather than to emancipate”, p. xx) for Terry Castle: “The ‘new’ eighteenth c. to be found in postmodernist scholarship is not so much an age of reason, but one of paranoia, repression, and incipient madness.” (p. xxi) 1 for Eric Hobsbawm (1997): These days, the Enlightenment can be dismissed as anything from superficial and intellectually naïve to a conspiracy of dead white men in periwigs to provide the intellectual foundation for Western imperialism. (p. xxi) Porter’s stance: considers Foucauldian and postmodern readings lopsided 1. because there was never a monolithic ‘Enlightenment project’ 2. thus: a. his study is neither advocacy nor apology b. he sees Enlightenment as neither good nor bad c. he rejects heroes-and-villains judgementalism 3. he sees enlightened thinkers as broad-minded, pluralistic; their tone ironic rather than dogmatic 4. he quotes Mark Goldie: “The Enlightenment was not a crusade but a tone of voice, a sensibility.” (p. xxi) 5. tolerance: a key word 6. suggests we view E. as ‘a cluster of overlapping and interacting élites who shared a mission to modernize’ (p. xxii) 7. quotes Locke’s dictum that we must understand a thinker’s terms “in the sense he uses them, and not as they are appropriated, by each man’s particular philosophy, to conceptions that never entered the mind’ of the author” (p. xxii) a. considers this v. imp. because “the world they were making is the one we have inherited, that secular value system to which most of us subscribe today which upholds the unity of mankind and basic personal freedoms, and the worth of tolerance, knowledge, education and opportunity.” (p. xxii) b. contradiction in this undertaking: while we can approve many of their causes, we reject others (i.e. ‘free men’/slaves; against criminalization of homosexuality/proposed castrating rapists and tattooing convicts c. Porter will explore the complexities, convolutions and contradictions 2 Chapter 1. A Blind Spot According to Kant (1784): Europe not enlightened, but becoming enlightened (not Enlightened Age but Age of Enlightenment) Yet, in many parts of Europe, incl. England, saper aude (dare to know) had been a guiding philosophy since early decades of the century Elitist male population believed they enjoyed a philosophical liberty in a free and progressive country So, why have historians tended to ignore the role of English thinkers in European Enlightenment? Traditional attitude towards ‘Age of Reason’: arid, pretentious interlude More recently: seen as movement decisive in making modernity New thinking among the reading public at large: stimulated via newspapers, novels, prints, even pornography Enlightenment: a revolution in mood, shock of the new, new ways of seeing, new protagonists (male and female), of various nationalities, discrete status, professional and interest groups Revisionist history of Enlightenment neglects British thinkers (for ex.,Godwin, Wollstronecraft, Adam Smith, Addison, Steele) Cassirer, transl. 1951 , The Philosophy of the Enlightenment: re. English thinkers “there is no thinker of real depth and of truly original stamp” Cassirer influential; his neglect of England passed on by his successors Term ‘Enlightenment’ did not come into English in mid-Victorian period See def. of E. in OED (p. 5) No books entitled “British Enlightenment; no widespread debate on English E. like that about scientific and industrial revolutions.; some studies exist on the political superstructure (Monarchy and Church) but they are partial in that they do not consider ‘society at large Question: why have critics neglected the English Enlightenment? The philosophs saw England as the ‘birthplace of the modern The French, the Italians, the Holy Roman Empire were great anglophiles. They celebrated England for: Constitutional monarchy Freedom under the law Open society Prosperity Religious toleration Voltaire’s Lettres philosophiques ou Lettres anglaises (1733) – considered the first attack on the ancien régime – quote p 6 England seen as the cradle of liberty, tolerance, sense Francis Bacon, the prophet of modern science Isaac Newton, revealed the laws of the universe John Locke, demolished Descartes and rebuilt philosophy on the bedrock of experience Diderot: quote p 7 Edward Gibbon commenting on Parisian’s view of the English p 7 3 British fiction popular on the Continent: Robinson Crusoe : up to 40 sequels in Germany by 1760 Ossian ‘The Scottish Homer’” Richardson (quote Diderot p 9) quote French critic 1768, p. 9 In spite of all this contemporary evidence suggesting “it was an English sun which lit up many of the Continental children of light” (p. 9), for many modern critics, the Enlightenment is normally thought of as a French phenomenon, Francophone, with metaphysical apotheosis among German philosophers. One explanation: modern critics are heirs (or prisoners) of an 18th view (held by Edmund Burke and Abbé Barruel) that the Enlightenment’s climax – or nadir – lay in ‘democratic revolution’ (ref. to American French revolutions); England had no comparable revolution. Who were England’s modernizers? (Quote p. 11) Recent scholarship (Quote p. 11) Need for better mappings (quote p. 12) Transformations in Britain during the long 18th c. Overthrow of absolutism Accelerating population growth Urbanization Commercial revolution marking rising disposable income Origins of industrialization “Shifts in consciousness helped to bring these changes about, to make sense of and level criticism at them, and to direct public attention to modernity, its delights and its discontents.: (p. 12) Changes in ‘high culture’ ( see pgs. 12-13) New sciences of man and society Hobbes, Locke, and their successors anatomized the mind and emotions Recognizable precursors of today’s social and human sciences too shape: Psychology Economics Anthropology Sociology Etc. In Britain, the Enlightenment was “primarily the expression of new mental and moral values, new canons of taste, styles of sociability and views of human nature. These found expression in: Urban renewal Establishment of: Hospitals Schools Factories Prisons Acceleration of communications Spread of: newspapers commercial outlets 4 consumer behaviors marketing of: new merchandise cultural services All such developments opened new social prospects and created new agendas of personal fulfillment Experiments in free-thinking, free-living, self-enrichment, pursuit of pleasure Bacon’s maxim “faber suae quisque fortunae” (‘each man [is] the maker is his own fortune’) Enlightened England’s pragmatism admired by foreigners British on Grand Tour shocked by the misery they met on continental Europe English pragmatism: not just worldliness, but also deriving from a philosophy of expediency, a dedication to the art, science and duty of living well in the here and now (p. 15) Belief that a cosmic benevolism blessed the pursuit of happiness (displacement of Calvinism) Britons set about exploiting a commercial society pregnant with opportunities, and the practical skills needed to drive it. (“‘great scramble’ of a market society”) (p. 16) Quotes, Priestley and Butler, p. 16 ‘Affective individualism’: “It has… been argued that it was enlightened England which brought, at least amongst genteel and professional people, the first flowering of ‘affective individualism’ within the conjugal family: greater exercise of choice as regards marriage partner, some degree of female emancipation from stern patriarchy, and for children from the parental rod.” (p. 16) “emancipation of the ego’ from tradition and judgementalism of elders, family, and peers; rejection of ancestral ‘moral economy’” (p. 16) “human nature was not flawed by the Fall; desire was desirable, society improvable, knowledge progressive and good would emerge from…man’s ‘endless cravings’.” (p. 17) “England’s free market economy, itself fanned by enlightened individualism, depended on consumerism permeating down through the social strata. With the renaissance of provincial towns, the growth of communications and service industries and the commercialization of news, information and leisure, an expanding public hankered to participate in pleasures traditionally exclusive to the élite.” (p. 18) quote Madame Roland (p. 18) “Reason was an attribute enjoyed by the whole nation, including women and the plebs.” (pgs. 1819) England was a society “dismissive of predestination and doubtful about ancestral pedigree per se, [and therefore] few aspirant males were automatically debarred by birth or blood.” (p 19) Strategies for achieving social inclusiveness (enlightened largesse giving the bien pensants the satisfaction of a superior sensibility): Philanthropy ‘Paternalism’ Charitable outlets (schools, hospitals, dispensaries, asylums, reformatories) 5 Another assimilation strategy lay in displays of social openness (mingling of people of different sex, age, rank, condition) at sporting events, spas, pleasure gardens, urban parades, etc.); also stagecoaches, coffee-houses (see quote, Prévost, p. 20) Belief that “commerce would unite those whom creeds set asunder: (p. 21, see quote, Voltaire, same page.) “The Enlightenment… thus translated the ultimate question: ‘How can I be happy?’” (p. 22) Solitude, “ ‘one of the greatest obstacles to pleasure and improvement’, bred hypochondria (the most fashionable illness among intellectuals) Social structures that promoted fellowship and good feelings: Coffeehouses, Masonic lodges, taverns, friendly societies, clubs “Human nature was malleable, people must cheerfully accommodate each other; good breeding, conversation and discreet charm were the lubricants which would overcome social friction, contributing ‘as much as possible to the East and Happiness of Mankind.” (p. 22) stress on ‘rational arts’ of: ease, good humor, sympathy, restraint and moderation See last paragraph of chapter, p. 23 6