Forthcoming: Writing Research and Pedagogy in the MENA Region

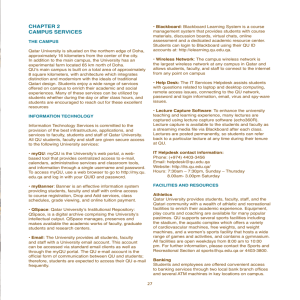

advertisement

Institutional Background The six American branch campuses in Education City, the multi-varsity project in Doha, Qatar, have a variety of approaches to building academic writing skills in their international student body. This discussion will offer two case studies, one from Virginia Commonwealth University in Qatar (VCUQatar) and Northwestern University in Qatar (NU-Q), to examine how trends in American pedagogy of writing are being modified, translated and adapted for use with a diverse student population. VCUQatar carries over the curricular requirements for writing from the main campus in Richmond, Virginia. Students across the fashion, graphic, and interior design majors, are required to take a two part sequence for first year writing. This is followed by a writing and research workshop, devoted to examination of research principles. The faculty in Qatar are required to use the core syllabus of assignments, objectives, citation style, and outcomes as the faculty on the main campus. The readings and individual assignments are determined by the instructor of record. This approach ensures curricular congruency and leaves the individual faculty with the task of modifying course content for the needs of his/her students. The First Year Writing program at NU-Q arose out of a concerted focus on the types of writing experiences students were having at the onset of their university experience and was developed by faculty in Qatar. The two part course sequence was developed to introduce students to the process of research and writing by breaking down the various steps incrementally. In the syllabus for the first semester of the course, the pedagogical framework is set out: “The writing process is intensely personal and will be treated as such in this course. To that end, multiple phases of the writing process will be carried out in class, such as workshop time and one-on-one conferences with the instructor.” Such a focus allows students to gain confidence in the development of their personal voice. This process based, personal approach is based on the strategies of Peter Elbow, along with the idea of scaffolding with assignments. Building on an established skill set occurs both within the individual assignments as well across the two semesters. The second part of the course is themed around research writing: “course to meet students where they currently are with respect to their academic writing and communication skills and to give them tools and support which they can continue to develop as they conduct research in coursework throughout their undergraduate study.” The NU-Q approach to first year writing is still being tried and tested, but after one semester, the strongest student writing has been in response to the Memoir assignment. The course has helped students in generating content, and creating meaningful messages in adherence with the conventions of academic writing. Comparing student responses to a New Student Orientation prompt with writing at the end of the semester provides evidence of this skill development. Elbow, P. (1994). Will the virtues of portfolios blind us to their potential dangers? In L. Black, D. Daiker, J. Somners, and G. Stygall (Eds.), New Directions in Portfolio Assessment: Reflective Practice, Critical Theory, and Large Scale Scoring (40-55). Portsmouth, NH: Heineman/Boynton-Cook. Rajakumar, Mohanalakshmi. 2014. Liberal Arts, Northwestern University in Qatar, Doha, Qatar. Microsoft Word file. Rajakumar, Mohanalakshmi. 2015. Liberal Arts, Northwestern University in Qatar, Doha, Qatar. Microsoft Word file. From “Good Design is Good Writing” By Mohanalakshmi Rajakumar Forthcoming: Writing Research and Pedagogy in the MENA Region VCUQatar, the oldest campus at Education City, recently celebrated its fifteen-year anniversary. The university offers majors in graphic, interior and fashion design, to students from the Middle East and South Asia. The VCUQatar focus on the liberal arts, inherited from VCU degree requirements, is indicative of standard North American training practices for art programs. The humanities and social science courses present foundational concepts key to the American higher educational experience (Salmon & Gritzer, 1990, p.60). These core curriculum requirements accompany the expectation that students will demonstrate a certain standard of academic writing. What most campuses don’t know, however, is how to support the development of writing without the benefit of the full-scale version of their home institutions. The broad variety of the students’ secondary experiences means that their first year at university is a calibrating opportunity; students from scientific schools, government schools, and international schools, with varying levels of English language and knowledge of critical thinking skills, find themselves in a classroom together. The curriculum of VCU main campus offers many instances in which students may focus on their academic skills and writing is one such common focus. The Focused Inquiry sequence, a two-part course taken in the first year, is a requirement in the common core curriculum across the majors. Students often resist this course and others like it, wondering why they have to take writing courses or read literature; both skills are required in the Focused Inquiry sequence as well as the other six writing intensive courses, which are part of their liberal arts requirements. VCUQatar students are not alone in this “lack of interest” as art students in the liberal arts as Salmon and Gritzer (1990) note in their survey of art students. An ongoing conversation among art educators is how to ensure that both art courses and the social sciences are “meaningfully integrated into the undergraduate education of design students” (Salmon & Grizer, 1992, p.78). In other words, faculty need to strategically think about how to make liberal arts courses these spaces in which students can understand view their education as a complete system rather than vocational preparation. One of the most interesting aspects of an integrated liberal arts and studies (LAS) core curriculum is the students’ reactions to the presentation of writing and textual material. “I don’t think as designers we need to read a novel,” a student wrote in a course evaluation for Focused Inquiry II after reading a novel as part of the fiction unit. “All of the assignments in this course were valid except for the case study,” noted another in response to the Writing in the Workplace unit on case studies. Students’ reactions to the intensive writing and reading requirements in these core classes demonstrates their lack of familiarity with the premise of a broad-based liberal arts approach to learning, which is systemic at American universities. Many strategies to overcome the liberal arts bias consider how the humanities methodology might be worked into design curriculum (Salmon & Gritzer, 1992, p. 78); the case of study of the first year writing courses at VCUQatar work the discussion the opposite way. How can design pedagogy and writing research work together to create more holistic writers and thinkers? From “Designers Have to Take Writing Classes” By Mohanalakshmi Rajakumar Published in Going Global: Transnational Perspectives on Globalization, Language, and Education Cambridge Scholars Publishing. October 2014. Pgs 154-168. Of particular interest to EFL research and pedagogy is how the second language context affects students in classrooms where more than half the learners are studying in their second language. Indeed, many students have three or more languages, with English among them. The insistence and contractual obligation of the universities to offer the same degree, and presumably the same pedagogical approaches, leave the individual faculty member to grapple with the variances in language abilities among their students. Some faculty members mimic the attitudes of American-based colleagues who feel that language ability is the responsibility of the English courses. Others make accommodation for students’ abilities, or encourage students to utilize resources on campus, such as writing centers. Educators are choosing strategies that are unique to the parameters of the Education City project, which provide new angles to the existing landscape of EFL teaching. While there are many nationalities enrolled in the various disciplines, classrooms are filled with a majority of students from across the Middle East. Nationality in the Arabian Gulf context is simultaneously multi-layered and yet flat as nationality is passed on from the father to the child, no matter the place of the birth. Therefore, an Indian student who has lived in Qatar all her life will remain Indian, rather than become Qatari. There is no naturalization process for anyone without a Qatari father. The social structures of the various nationalities living in the country can be preserved within one’s ethnic identity; parents can send children to schools with the curriculum from their home country, attend functions organized by their embassy or cultural group, shop at stores carrying their products, and in the case of the various Christian denominations, worship in structures dedicated to their faith. Despite this holistic approach to identity, there are exceptions, and one of these is primary and secondary schooling. (Another is privatized health care.) Many Arab, even Qatari, families send their children to international primary and secondary schools instead of the independent or government schools overseen by the Supreme Education Council. These students are educated by expatriate teachers with an expatriate curriculum that is often more similar to the expectations/materials of the universities in Education City. That they are in classrooms with students who have attended an ethnically identified school, such as the Modern Indian School, or Middle East Technical School, further diversifies the university setting. Perhaps more than in most cases, a students’ secondary school preparation can affect their university success, at least in the first year. Faculty comment that while students may enter the branch campus at different levels, after four years, each cohort leaves with the skills expected of graduates from a North American environment. The varied level of the secondary experience is a cause of academic intervention by the various institutions. Weill Cornell Medical College, for example, has instituted an intensive two-year pre-medical program with a considerable liberal arts requirement in an effort to standardize student abilities prior to beginning the medical program. Some argue this disadvantages the students as they are completing four years of a standard North American bachelors program in two; on the other hand, these students can transfer after two years to another university, as do Biology majors at Carnegie Mellon University in Qatar, and have been well prepared with solid academic credentials. The addition of Biology at Carnegie Mellon University in Qatar is an example of the ongoing curricular negotiation and adaptation happening across Education City as the entire project continues to mature and develop. The secondary school backgrounds, academic abilities, and language capacities of students in Education City vary widely across the various branch campuses. The model is very much a vocational training approach to higher education where students enroll in a specific degree with a specific type of major: when applying they make a conscious choice toward either engineering or design, international studies or business administration.