título del proyecto - La Colina's English Department

advertisement

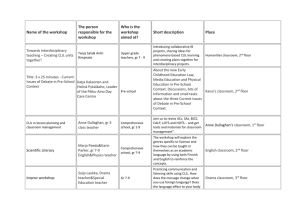

TÍTULO DEL PROYECTO: Introducción al diseño curricular de 4to año: Inglés

FORMATO DE CAPACITACIÓN: Curso

DESTINATARIOS: Docentes de Inglés de Educación Secundaria

LOCALIZACIÓN: Provincia de Buenos Aires

MODALIDAD: Presencial

RESPONSABLES: Dirección de Capacitación

AREA: Lengua Extranjera (Inglés)

Unit 1:

REFLECTION TASK: We are going to analyse two activities that we would

normally find in 4º ES.

Consider the following two examples. See if you can fill in the gaps.

What differences can you find between them in terms of format, focus,

language, audience?

1. In the UK some twenty per cent of the population is of pensionable age. It

is a proportion that is increasing. The map, (Figure C) shows that the life

expectancy at birth is over 70 years in the developed world, __________ in

the developing world it is much lower.

2. In the UK there............ (be) a lot of pensioners because elderly people

............ (live) 70 years or more now.

Anchor Point: Language teaching flaws

We said ... that language teaching seems to have problems related to its content. The

basic flaw seems to reside in the fact that its conceptual content – topics, themes,

stories – all of which can occur in a wide range of media, are subordinated to the

underlying linguistic objective. The content that gives life to language, that illustrates it,

that advertises it, that nurtures it – is all too often sacrificed on the altar of language

practice. And of course, how can it be any different? If our objective is to assess

language items and structures, then it is those aspects that we must teach.

Anchor Point: Subject teaching flaws

But what about the other world of subject teaching? If we say, for now, that a major

flaw in language teaching is one of content, we might be further tempted to suggest

that language teachers, on the whole, are accustomed to dealing with content from a

linguistic perspective, and not so much from a conceptual perspective. This is surely

true. Language teachers are trained to use thematic content in a certain way (so that it

becomes a vehicle for the illustration of language use), and we are arguing that the

conceptual aspects (non-'linguistic') of that content are too often

'disposable'. Remember? Who cares about the Amazon rainforests as long as I can

use the 2nd Conditional? Because that's what the teacher's going to test me on!

Anchor Point: Subjects and their language

Subject teachers, on the other hand, are trained to do exactly the opposite. For them,

no part of their syllabus content is either throwaway or disposable. A teacher of

Biology will teach the concept of photosynthesis using all the content and procedure

that is required to make that concept understood. What this teacher might not have

considered are the language elements.

1

How can we talk of 'subject related skills' unless we also mention language? Surely,

language is in itself 'content', and should be an explicit part of all subject-teaching?

Scientific discourse is different from the discourse of social science. Talking about art is

very different from talking about mathematics. The differences exist on both a lexical

and a structural basis, and even in primary school children are expected, to some

extent, to understand, master and manipulate this language. This language is often

referred to as text-type, and it is the crucial building-block in the conceptual

architecture of any academic discipline.

Anchor Point: Lexis and grammar

You will have noticed, if you filled in the gaps successfully, that the examples use

words that occur in many topical contexts. But the grammar of those examples shows

how these words are used in the specific discourse style of the subjects, in these cases

Science and Geography. In example 1, the gap could be filled by various verbs (write,

put…) but the word 'record' is a more accurate reflection of the academic function

required, in the context of a (basic) scientific experiment. To 'record' is not the same as

to 'write'. In example 2, 'but' might be acceptable as the missing word, but the less

common word 'whereas' is the better, more text-appropriate answer.

Students do not simply 'pick up' this type of language, to then use it immediately and

correctly. By reading and working with the examples, they are being inducted into the

world of subject-specific discourse, but the question of whether they learn to

understand and then to use this type of language depends on many factors. Subject

teachers need to be trained in order to make this language salient, to make it stand out

and to help it do its conceptual work.

Ball´s ideas relate to what Mohan and Slater (2005: 155-156) say about the

relationship between content and language:

What is content? A traditional view of language does not offer a way to theorize content

or meaning in text or to engage with the relations of language and content. A traditional

view of language, as Derewianka (2001) described, is concerned with the form and

structure of language. It operates at the level of the sentence and below and does not

recognize context as significant. It sees language as a set of rules which allow us to

make judgments of correctness, and it sees language learning as the acquisition of

correct forms. Consistent with this view, a focus-on-form perspective would look at a

content classroom and ask whether the students are engaged in tasks and topics that

highlight certain features of the grammar which may be considered problematic for

students (Long & Robinson, 1998) and offer opportunities for students to practice these

difficult constructions. Similarly, Pica (2002) proposed that content-based language

teaching should include more opportunities to focus on intervention strategies which

would assist in the noticing and correction of grammatical errors.

Derewianka noted that, in contrast to the traditional view of language, a functional view

is based on the functions that language serves within our lives. It emphasizes the text

or discourse as a whole in relation to its context, and recognizes that lexis and

grammar vary with text and context. It sees language as a resource for making

meaning and provides tools to investigate and critique how language is involved in the

construction of meaning. It sees learning language as extending one's potential to

make meaning in a broadening range of contexts, including academic discourse in

schooling. Consistent with this view, we will examine how a teacher helps young ESL

learners to understand and talk about a simple theory or model of magnetism in an

2

appropriate scientific register and to apply the theory to reinterpret their practical

contexts of experience. In particular, we use a functional perspective to examine the

role of scientific theory and practice in teaching and learning language and science.

A functional view of language offers a way to characterize content and language.

Broadly speaking, content is the meaning of a discourse and language is the wording

of a discourse. Consider the following text, an ESL child's explanation of magnetism:

“North and north doesn’t go together because it's the same. If north and south go

together, because it's not the same, they will attract” (Slater, 2004, p. 169). Reading

this explanation for content, a science teacher might see this as a causal explanation of

magnetism. Reading it for language, a language teacher might note the “if” and

“because,” and the technical terms “north,” “south,” “attract.” Bringing the two together,

a functional view of language could say that the meaning of this discourse is a causal

explanation of a science topic, and this meaning is expressed in the wording (e.g.,

causality is expressed by “if” and “because,” and technical terms of magnetism are

used). If we look beyond the text or discourse to a larger unit of meaning, the social

practice of doing science, the relation between content and language can again be

seen as a link between meaning and wording.

How can content and language be integrated in an English class through

teaching practices? How are meaning and wording linked in our teaching

practices in ES 4º?

ANALYSIS TASK:

PART A:

Sabrina is planning her classes for 4º ES. She is teaching in a school in La Plata

that is oriented to social and natural studies. She has chosen a number of texts

to work with during her lessons with the social studies group.

Analyse Sabrina´s choices.

In what ways are these examples of language-content integration?

a. What challenges are posed to the teacher in order to teach the language

using this text?

b. Use the curriculum design. Draw the content that you think will be taught

during the lessons (from a linguistic perspective). What language are

students expected to have already?

c. What content from social studies is being developed here?

PART B:

Now Sabrina is starting to plan her classes. She has decided to develop a first

unit on social geography called “Population and development”. This unit will

take her approximately 14 classes plus test.

Sabrina is considering the following directives from the curriculum design:

Se sugieren los siguientes pasos teniendo en cuenta los tres elementos a trabajar en

el enfoque AICLE:

Procesamiento del texto:

3

El docente guiará a los alumnos para que analicen la ilustración, los títulos y

subtítulos y lleguen a la comprensión global del tema del artículo. (Estrategias

de aprendizaje)

Identificación y organización del contenido: Los alumnos discutirán el contenido

del artículo teniendo en cuenta los conocimientos que ellos tienen del tema

estudiado en biología. (Contenido)

Explotación de la lengua extranjera: El docente se concentrará en los

contenidos gramaticales presentes en el artículo (E.j. Uso de Present Perfect

para expresar acciones que continúan hasta el presente, will para expresar

predicciones, etc.) y la explotación de los contenidos léxicos y fonológicos.

(Lengua extranjera)

Tareas a realizar por los alumnos:

Los alumnos realizarán tareas que les permitan seguir profundizando el contenido y

practicando la lengua extranjera (Ej. realizar un mapa conceptual resumiendo el

artículo, debate sobre el contenido del mismo, etc.)

How is Sabrina going to organize the first classes using pages 8 and 9 from “The

New Wider World” Manual? Plan the first 2/3 lessons in groups of 4 using the

directives above.

Principle 2: The Primacy of task

Methodological frames: the primacy of 'task'

If you study history in a foreign language, for example, then you are immediately faced

with a large amount of text. The text has often been designed for L1 consumption. In

this example, for Spanish sixteen-year-old students, the activity attempts to

differentiate between Socialism, Communism and Marxism. Here is an extract from the

text:

The German philosopher, Karl Marx, went further than socialism.

He thought that Liberalism was 'false liberty' and thought that the

famous 'Declaration of the Rights of Man' of 1789 was focused too

much on the individual. The individual had liberty, but to do what?

Marx wanted society to be communal and controlled, not

individualised. He thought that eventually the proletariat would

come to dominate the bourgeoisie and then control the means of

production.…

The above is an intimidating text for a native speaker, let alone a CLIL student. But the

reigning philosophy of CLIL would appear to be that there is no such thing as a difficult

text.

This is easily illustrated. Look at the possible questions that could follow (or precede)

the above (partial) text on Marxists, Socialists and Anarchists. Which of the four

questions do you think is the 'easiest' to do, and why?

Q1. Read the text on Socialism, Marxism and Anarchism. Compare and contrast the

three ideologies.

4

Q2. Define the three movements in terms of their principal ideological bases.

Q3. Read the text on the three movements and answer the questions that follow.

Q4. Do not read the text yet. Below you will see various opposites to the philosophies

of socialism and communism.

Now read the text, extracting the word or phrase that opposes the idea expressed

below. The first one is done for you.

Opposite idea

Socialist or communist idea

Working alone, to improve your life.

Working together

Individuality

Solidarity

Privileges

Class-based society

Wealth for the minority

A society of individuals

A 'free' society

The bourgeoisie control the proletariat

The bourgeoisie control production

If you chose Q4 as being the most accessible, then you will have thought about various

reasons for your choice. But whatever you thought, it should be very clear that it is not

the text itself that is the problem, but rather the relative complexity of the tasks. It is

simply untrue to say that you could not ask a 9 year-old child to work on the text above.

It simply depends on what you ask the child to do. If you asked a 9 year-old child the

following questions about the previous text on Marx et al:

a) What was Marx's other name?

b) Which country did he come from?

c) When was the Declaration of Rights written?

…then the child would have a decent chance of getting the questions right. The tasks

are rather 'light', but it might depend on our didactic objective. Similarly, we might say

that Q1 above is, if not exactly 'light', then maybe unnecessarily complex - and what is

our objective? Q4 is much better because it provides 'scaffolding'. Scaffolding breaks

down the ideas into digestible chunks. Q4 provides a conceptual framework whereby

the contrasts become the reason for doing the task. The instruction even tells the

student not to read the text beforehand. The text is read as part of the task.

Language focus

Q4 is also much more linguistic in its scope because it is asking the students to focus

on the language that enables them to find the contrast. So 'privileges' can now be

contrasted as 'Lack of privileges' - employing a useful formal item (lack). Class-based

society will be 'Classless society', enabling the teacher to show how this word is formed

by using the suffix 'less' (where other words in social science may later behave in a

similar fashion). The term 'minority' will now become 'majority', the society of individuals

will require the word 'collective' or 'communal' to form its contrast, etc. The activity is

5

powerful, on both a cognitive and linguistic level. Once it has been done, the student

might then be asked (more reasonably) to attempt questions 1 & 2. The

complexity/simplicity of the text is not an issue. There is no such thing as a difficult text

in an educational/scholastic context. But there are such things as difficult and easy

tasks.

Activity types

If we look at the practice of teaching within this new equation, we need to be able to

limit the approaches that reflect the combination of communication and skills. By

limiting, we clarify the boundaries of practice that can achieve this goal.

In CLIL, there appear to be four basic types of activity that can help students to

prosper, despite their relative lack of linguistic resources. These types are applicable to

both primary, secondary and post-compulsory education.

1. Activities to enhance peer communication

(assimilate conceptual content + communicative competence)

2. Activities to help develop reading strategies

(where texts, often authentic, are conceptually and linguistically dense)

3. Activities to guide student production (oral and written)

(focus on the planning of production - 'minimum guarantees')

4. Activities to engage higher cognitive skills

(make students think - offer more opportunities for employing a range of operations)

Number 1. Here, the activities are designed to enhance the assimilation of the

conceptual content at the same time as developing communicative strategies. We've

already seen two examples of this - the 'Running Dictation' about the planets from

Article Two ('How do you know if you're practising CLIL?') and the Information-Gap

Crossword about 'The Accumulation of capital' in Article 3 ('Language, concepts and

procedures. Why CLIL does them better!'). In order to breach the 'gap' in both cases,

the students had to write definitions, and then communicate them. The activities revise

concepts already learned in a unit, but not necessarily assimilated.

The students:

o Write

o Speak

o Listen

o Interpret

o Engage in contextualised grammar

…whilst assimilating the economic concepts that form the conceptual objective of the

lesson. How many birds would you like to kill with one stone?

Number 2 is well illustrated by the Marx example from this article. The activity type

recognises the probability that if the students engage in real content, they are more

likely to confront a greater amount of text, often authentic. The students are therefore

guided in their reading. Instead of reading the text in order to then perform a deductive

task (so often the case in standard language and subject teaching), the task involves

the reading itself and leads the students to the key content. The key content will relate

to the conceptual objective.

6

In Number 3, the activity type acknowledges the fact that in order to speak (or write)

students need to have something to say! So instead of the instruction so beloved of

language-learning textbooks:

Turn to your partner and ask him/her if she plays any musical instruments.

…an exchange that can logically culminate in the dialogue 'No' (Or, 'No I don't' if the

author's intention were more linguistically ambitious!) In CLIL it is possible to do rather

more. The students simply work on more complex content, with activities which involve

stages of preparation for subsequent production. The preparation provides a 'minimum

guarantee', after which students (depending on their ability or interest) can improvise

further.

Number 4 acknowledges the power of meaningful engagement. According to

psycholinguists, the more higher operations are involved in a task, the greater the

probability of linguistic retention. The higher the level of thinking involved, the more

likely the assimilation of the vehicular language.

And finally...

To sum up, whether or not the acronym CLIL will exist in ten year's time is probably

irrelevant. The educational approach that it seems to encapsulate is in the here and

now. David Graddol's important book 'English Next' (3) has made this very clear. The

future is about 'competences', not about discussing the differences between the Past

Simple and the Present Perfect. This is not to imply that CLIL does not work on, or that

it is uninterested in, accuracy. What it does imply is that the development of

competences is much more likely to occur within an approach that prioritises thinking

skills and communication.

ANALYSIS TASK:

Sabrina prepared a handout (Appendix 1) with tasks to carry out with the text.

Analyse it and decide if any changes could be done to the tasks to make them

more appropriate for her teaching context.

Appendix 1

7

Principle 3: The development of cognitive strategies as a support for language

use in the class.

Anchor Point: BICS & CALP

They sound like diseases, but don't worry; they're not. In 1979 a Canadian linguist

called Jim Cummins introduced two very important acronyms of the world of education

– BICS and CALP. By BICS he meant Basic Interpersonal Communicative Skills, which

children pick up in the playground and at home and which is more related to what we

might call 'conversational' survival. By CALP he meant Cognitive Academic Language

8

Proficiency, which is the kind of language that you NEVER hear in the playground, and

quite rightly so! The word 'whereas', in example 2 above, is at the weak end of the

CALP scale because you could get away with the word 'but'. However, when you get to

a scary word like 'photosynthesis' it's a whole different ball game.

Anchor Point: Language as the key element in learning

By fusing the worlds of language and subject teaching, CLIL is helping everyone to

focus on the importance of language as the key not just to academic success but as

the key to normal educational practice. CLIL has not discovered this, of course. The

Language Across the Curriculum movement in the 1980s in both the UK and the USA

recognised the importance of language in the subject world, but again, in a CLIL

context that works, this approach occurs almost by default. When you are not teaching

native speakers, you tend to focus more on how you are going to get the concepts

across, which brings us back to procedures.

Anchor Point: 'Skill' rhymes with 'CLIL'

We are constantly being told that the future of education resides in a new emphasis on

skills and competences. The European Commission has published a list of 'key

competences' for what it calls 'lifelong learning', and curriculum planners are now

expected to incorporate these ideas across subject areas. This is good news for CLIL,

because it is already functioning along these lines. There is no separation, in CLIL, of

the worlds of concepts, procedures and language.

Consider the difference between these two lessons – (1) from a standard social

science native-speaker syllabus, and the other (2) from a CLIL-based programme

using the same content.

Ask yourself these questions:

a.

b.

c.

d.

Which activity is cognitively more challenging?

Which activity is the most appropriate for building knowledge?

Which activity offers the most opportunities for language use?

When and for what would you use each activity?

ACTIVITIES

ACTIVITY 1

We have looked at some terms and concepts related to finances and to the

accumulation of capital. Before we continue, try to match these definitions to their

terms.

Definition

People who supply us with materials

Part-owner of a company

Amount of money charged for the use of a loan

To set aside an amount of money recovered from investments in a given year

Portion of profits distributed to shareholders in proportion to their shareholdings

Portion of profits retained to finance expansion

Pay to employees in exchange for their labour

9

Money received by the company for the sale of goods or services

Portion of money received that remains after paying for materials, wages, investments

Term

Interest

Write off

Company capital

Suppliers

Earnings

Profits

Shareholder

Dividends

Wages

ACTIVITY 2

Define these terms in pairs, as in the example given. Then find a partner from Group 'B'

who has the other part of the crossword. Take it in turns to read out the definitions. The

listener must try to supply the correct term.

(Group A)

Across:

1. When you borrow money, you normally

have to pay this every month to the bank.

Down:

Anchor Point: Procedures and cognition

In answer to a) – (which activity is more cognitively challenging?), we might answer,

who cares? Both activities end up at the same conceptual point. But the crucial

difference between the L1 activity and the CLIL equivalent is that the latter does not

present the concepts all tied up in a perfect package. In Example 2, the students must

go back over their materials and find out for themselves (in case they've forgotten)

what the terms mean, and then they are obliged to frame them within a linguistic model

that is provided, but only partially so. The example sentence (defining 'Interest') cannot

10

be simply copied for the other terms. The concept will determine the exact language

frames required. It's not easy, but it's possible. Nevertheless, it is procedurally rich.

In example 1, on the other hand, the language is provided, and although it is complex

and requires a certain level of language to understand it, it still 'spoonfeeds' the

students. All they have to do is to match. It is procedurally quite poor.

In answer to question 2 (Which activity builds knowledge the best?) the answer is

obvious. Both activities have the same surface objective (to learn and understand the

terms), but the differing processes suggest that the Crossword will be a more

significant learning experience - even if it might lead to more mistakes and language

errors along the way. A student is more likely to remember the lesson, and to

remember the effort he or she made in fulfilling the procedural

demands. Psycholinguists have been telling us for years that significant learning is

more deeply processed and assimilated. So why not do it?

In answer to question 3 (Which activity offers the most opportunities for language use?)

it hardly needs explanation. The activity is an information-gap type activity imported

from the world of language teaching – it's not the kind of lesson you'd expect to see in

a social science book – but consider the range of skills it works on. Writing (defining),

reading (when you look at the gaps during the game phase), speaking and

listening. Moreover, the listening required is intensive. The listener needs to

understand, and therefore the speaker needs to be clear and grammatical! The

students also need to work together cooperatively both in the preparation phase and in

the game phase. In the matching activity, the teacher could feasibly say 'Do this for

homework', which is kind of sad... Competences? Game over!

In answer to question 4, (When and for what would you use each activity?), you could

argue that Activity 1 is better for just revising the concepts and moving on, and you'd

probably be right. But the objective smacks of teacher convenience, as opposed to

student benefit. With Activity 2, the teacher is bringing a whole lorry-load of educational

objectives to the lesson, and pouring them onto the classroom floor. Who cares if it

takes two lessons, and the other activity takes ten minutes? We're talking about

educational pay-off here, and when CLIL is done well, that's what you get.

Brewster´s article:

Introduction

In CLIL lessons the cognitive challenges of language learning are great; much of the

content lies outside children's direct experience and is often more abstract. For

example, in science lessons learners may struggle to describe and compare the

properties of materials, may find it impossible to hypothesise about why particular

materials are used for particular purposes. They may be able to write up the procedural

part of a report after testing materials but not how to write conclusions. By being taught

specific thinking skills and the associated language, learners are better equipped to

deal with the complex academic and cognitive demands of learning school subjects in

a foreign language.

Basic Interpersonal Communicative Skills (BICS) and Cognitive Academic

Language Proficiency (CALP)

In 1979 the Canadian educator, Jim Cummins, made a useful distinction between

BICS, the skills of listening, speaking, reading and writing for so-called social or

11

conversational purposes and CALP, linked to more academic, cognitively challenging

tasks in subject lessons. The work of Biber (1986) and Corson (1995) provided

evidence of the linguistic reality in the distinction between BICS and CALP. This

original distinction, refined over time in response to some criticisms, has continued to

provide useful insights for many CLIL teachers.

Typical language and thinking in tasks

If learners are experimenting with different colour combinations in an art class, trying

out magnets in the science class or investigating the lines of symmetry of 2D shapes in

maths lessons, what kinds of skill, aside from basic language skills, will they need to

draw on or develop? Learners may be encouraged

·

to predict what will happen,

·

to carry out simple investigations or experiments,

·

to describe and record what they observe,

·

to find patterns, notice similarities and differences,

·

to compare results, to draw conclusions and so on.

If we take the example of predicting, learners may know the use of will/ going to for an

easy, everyday situation. However, with little knowledge of the concept of magnetism,

for example, learners may not be able to think very clearly about their intended

meaning and may not know the subject-specific words of attract or repel. Some

children find it difficult enough to draw on these more academic kinds of interaction in

their first language, never mind a foreign language. As John Clegg wrote in an earlier

article: The truth is that schools don't often teach these skills explicitly. Instead,

teachers hope that their learners will pick them up.

The first section of this article will refer briefly to the renewed interest in teaching

thinking skills, often based on modern re-conceptions of the traditional taxonomy of

thinking skills published by Benjamin Bloom in 1956. This categorization and ordering

of thinking skills involves a discussion of how the so-called lower-order thinking skills

should ideally lead onto the teaching of higher order thinking skills. The next section on

process skills outlines those skills typically required in different stages of concept

development in subject lessons. Finally, there will be a brief example of how the use of

graphic organizers to record and interpret information links thinking skills to process

skills and language skills.

Teaching thinking skills

Today there is international recognition that education is more than just learning

knowledge and thinking, it also involves learners' feelings, beliefs and the cultural

environment of the classroom. Nevertheless, the importance of teaching thinking and

creativity is an important element in modern education. Benjamin Bloom was the first to

develop a highly popularised hierarchy of six thinking skills placed on a continuum from

lower to higher order skills: knowledge, comprehension, application, analysis, synthesis

and evaluation. According to this system, lower order skills included recalling

knowledge to identify, label, name or describe things. Higher order skills called on the

application, analysis or synthesis of knowledge, needed when learners use new

information or a concept in a new situation, break information or concepts into parts to

12

understand it more fully, or put ideas together to form something new. Bloom's

structure was a useful starting point and triggered many applications to school activities

and curricula.

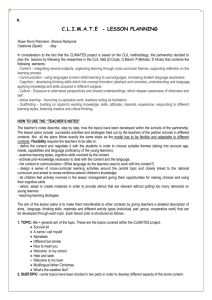

Bloom's revised taxonomy of thinking skills

In 2001 a former student of Bloom, Lorin Anderson, published a revised classification

of thinking skills which is actually rather similar to the original but focuses more on

verbs than nouns and renames some of the levels.

Fig. 1 Bloom's Revised Taxonomy

Higher Order Thinking Skills

Creating

making , designing, constructing,

planning, producing, inventing,

Evaluating

checking, hypothesising,

experimenting judging, testing,

monitoring,

Analysing

comparing, organising, outlining,

finding, structuring, integrating

Applying

implementing, carrying out, using

Understanding

comparing, explaining, classifying,

exemplifying, summarising

Remembering

recognising, listing, describing,

identifying, retrieving, naming, finding,

defining

Lower Order Thinking Skills

We can see that these levels have an intuitive appeal to many teachers; however it can

also be difficult to implement some of these ideas. For example, comparing falls both

under analysing and understanding, which is confusing. Here analysing the level of

comparison depends on context, for example: how complex is the concept or

knowledge being compared?

Linking thinking and language

The figure below is an example of how publications on thinking skills began to start

linking some common thinking and process skills with the typical language required.

For reasons of space, only three levels are exemplified.

Fig. 3 Typical thinking and language skills

Thinking skill

Remembering/ Recall

recognising, listing, describing,

identifying, retrieving, naming, finding,

Possible Language

Questions using who, what, where, when,

which how, how much?

Tasks using describe, choose, define, find,

13

defining

label, colour, match, underline key

vocabulary in different colours (e.g. parts of a

system and functions)

Language:

That's a …(because it has …and … )

This is a … and this is what it does.

This has…

This is a kind of …. which/that …

A … is a kind of… which/that …

This goes with this.

Understanding/ Interpreting

comparing, explaining, exemplifying,

classifying, understanding cause and

effect, generalizing, summarising,

Questions using is this the same as…?

What's the difference between…? Which part

doesn't fit or match the others? Why?

Tasks using classify, explain, show what

would happen if… give an example, show in

a graph or table, use a Venn diagram or

chart to show…

Language:

This is ..( a kind of…) but that one isn't

(because…)

This has ( a type of…)but that one

doesn't/hasn't (because…).

These are all types of …because

This belongs/ goes here because…

If we do this then…

This leads to..

This causes …

Applying to new situations

Planning, implementing, carrying out,

drawing conclusions, reporting back

Questions using what would happen if..?

What would result in …? How much change

is there if you …?

Tasks using Explain what would happen if…,

Show the results of…,

Using investigations and experimental inquiry

e.g. surveys, web quests etc. choosing how

to record and represent information

Language:

A variety of language functions for planning,

hypothesising, asking questions, reporting,

drawing conclusions e.g.

What shall we try/ do first?

if we try this then ...that could be…

First we thought about… then we…This must

be .. because…

It can't be …because…

14

Marzano's taxonomy of skills in education

In 2000 Marzano published a different way of looking at skills. His classification is

based on the Knowledge Domain and three systems - the Cognitive, the Self and the

Metacognitive. The self system involves a learner's attitudes, beliefs, and feelings that

determine his/her motivation. The metacognitive system relates to learning to learn: it

helps the learner to set goals, make decisions about and monitor which information is

necessary and which cognitive processes are the best fit for the task in hand.

Fig. 2 Marzano's New Educational Taxonomy

KNOWLEDGE DOMAIN

Information

Mental Procedures

Physical Procedures

COGNITIVE SYSTEM

Knowledge

retrieval

Comprehension

Analysis

Knowledge Use

Recall: Recalling Synthesis: identifying Matching, classifying, Decision-making,

information,

what is important to

error analysis,

problem-solving,

facts, sequences

remember.

generalizing and

experimental

and processes.

specifying: by

inquiry,

engaging in these

investigations.

Representation:

cognitive processes

These are also

putting this

learners use what

especially useful in

information into

they learn to create

project-type work.

categories.

insights and invent

ways of using

Graphic organisers

learned information in

encourage this

new situations.

process.

The knowledge domain, consists of three categories of knowledge: information, mental

procedures and physical procedures. A child at primary level may learn about

quadrilaterals and the key vocabulary and characteristics to describe them. This is the

what of knowledge. She will also learn how to draw different kinds of quadrilateral

(physical procedures) and how to compare or classify them (mental procedures). The

cognitive system is made up of four components:

·

·

·

·

knowledge retrieval,

comprehension,

analysis, and

knowledge use.

Marzano's cognitive system is similar to the six levels of Bloom and Anderson. In

knowledge retrieval (cf. Remembering and Understanding) the child needs to be able

to identify and put a name to new information; for example, the topic might be

mammals and the names of different types of big cat, such as tiger, lion, cheetah and

so on. Facts about mammals will involve statements and generalizations using the

simple present tense, such as:

15

·

·

·

·

·

·

mammals have a covering of fur, hair, or skin,

mammals give birth to live young,

mammals are warm -blooded,

mammals feed their young with milk from the mother,

tigers have stripes but cheetahs and leopards have spots, etc.

tigers can swim

These language functions can be linked to all four basic language skills using activities

based on oracy (speaking and listening) and literacy tasks (reading and writing). For

example, learners can listen to descriptions of animals and choose the correct picture,

use a tick chart to listen to comparisons of big cats and then use this as a speaking

frame to produce simple sentences. Learners might read simple descriptions of big

cats and transfer key information onto a chart, then use this chart to write simple

sentences. This basic knowledge can be extended to compare and classify types of big

cat in different ways according to features such as habitat, characteristics, appearance

etc.

Under comprehension the learners sort out which information is important or relevant

for a task and ignore other information. Graphic organizers such as charts, grids, Venn

diagrams and flow charts are especially important here for learners as they organize

information in a way that reduces the language load. Thus they help the learner to

focus on the key language and thinking required.

In analysis the learners need to draw on more complex thinking processes - matching,

classifying, generalising and specifying - in order to create and invent new insights or

new ways of using learned information. These skills are likely to be highlighted when

carrying out investigations. Knowledge use is the highest form of thinking process

under Marzano's system and is used particularly in the creation of investigations,

projects and web quests, where application and the creation of new ideas are

particularly useful.

Conclusion

These attempts to analyze and classify thinking processes move from a foundation of

simpler, lower order skills to more complex higher order skills. However, there is still no

consensus about the exact number of skills or levels, the interaction between them nor

is it easy to analyse the level of difficulty of a particular task or the precise thinking

skills required. All we can do for now is draw on insights that have been made and see

which ones seem to fit in with our views. The next article focuses on process skills and

data-handling, referring particularly to the use of graphic organizers to record and

interpret data. The importance and benefits of graphic organizers for both learners and

teachers will be described and how teachers can plan for them. Different types of

organizer will be outlined and one type called glyphs will be illustrated in some detail.

ANALYSIS TASK: From this description, analyse the activities developed by

Sabrina and spot what cognitive strategies are involved in each task.

TASK :

How were these characteristic/ core features seen in Sabrina´s work? Assess her

work. Do you think if follows the core features that Marsh, Mehisto and Frigols

point out for CLIL?

Core features of CLIL as a synthesis (From Marsh, Mehisto and Frigols)

16

Multiple focus

• supporting language learning in content classes

• supporting content learning in language classes

• integrating several subjects

• organizing learning through cross-curricular themes and projects

• supporting reflection on the learning process

Safe and enriching learning environment

• using routine activities and discourse

• displaying language and content throughout the classroom

• building student confidence to experiment with language and content

• using classroom learning centres

• guiding access to authentic learning materials and environments

• increasing student language awareness

Authenticity

• letting the students ask for the language help they need

• maximizing the accommodation of student interests

• making a regular connection between learning and the students' lives

• connecting with other speakers of the CLIL language

• using current materials from the media and other sources

Active learning

• students communicating more than the teacher

• students help set content, language and learning skills outcomes

• students evaluate progress in achieving learning outcomes

• favouring peer co-operative work

• negotiating the meaning of language and content with students

• teachers acting as facilitators

Scaffolding

• building on a student's existing knowledge, skills, attitudes, interests and experience

• repackaging information in user-friendly ways

• responding to different learning styles

• fostering creative and critical thinking

• challenging students to take another step forward and not just coast in comfort

CO-operation

• planning courses/lessons/themes in co-operation with CLIL and non-CLlL teachers

• involving parents in learning about CLIL and how to support students

|

• involving the local community, authorities and employers

As a synthesis we can refer to what Mehisto, Marsh and Frigols (2008) say about the

three CLIL related goals.

CLIL foundation pieces

The CLIL strategy, above all, involves using a language that is not a student's native

language as a medium of instruction and learning for primary, secondary and/or

vocational-level subjects such as maths, science, art or business. However, CLIL also

calls on content teachers to teach some language. In particular, content teachers need

to support the learning of those parts of language knowledge that students are missing

and that may be preventing them mastering the content.

17

Language teachers in CLIL programmes play

a unique role. In addition to teaching the

standard curriculum, they work to support

content teachers by helping students to gain

the language needed to manipulate content

from other subjects. In so doing they also help

to reinforce the acquisition of content.

Thus, CLIL is a tool for the teaching and

learning of content and language. The

essence of CLlL is integration. This integration

has a dual focus:

1) Language learning is included in content classes (e.g., maths, history, geography,

computer programming, science, civics, etc).This means repackaging information in

a manner that facilitates understanding. Charts, diagrams, drawings, hands-on

experiments and the drawing out of key concepts and terminology are all common

CLIL strategies.

2) Content from subjects is used in language-learning classes. The language teacher,

working together with teachers of other subjects, incorporates the vocabulary,

terminology and texts from those other subjects into his or her classes. Students

learn the language and discourse patterns they need to understand and use the

content.

lt is a student’s desire to understand and use the content that motivates him or her to

learn the language. Even in language classes, students are likely to learn more if íhey

are not simply learning language for language's sake, but using language to

accomplish concrete tasks and learn new content. The language teacher takes more

time to help students improve the quality of their language than the content teacher.

However, finding ways in the CLIL context to inject content into language classes will

also help improve language learning. Thus, in CLIL, content goals are supported by

language goals.

In addition to a focus on content and language, there is a third element that comes into

play. The development of learning skills supports the achievement of content language

goals. Learning skills goals constitute the third driver in the CLIL triad.

The three goals of content, language and learning skills need to fit into a larger context.

Parents are most interested in having their children learn the CLIL language, continue

to develop their first language and learn as much of the content as children who are not

in CLIL programmes. Therefore, the ultimate goal of CLIL initiatives is to create

conditions that support the achievement of the following: _,

• grade-appropriate levels of academic achievement in subjects taught through

• the CLIL language;

• grade-appropriate functional proficiency in listening, speaking, reading and writing in

the CLIL language;

• age-appropriate levels of first-language competence in listening, speaking, reading

and writing;

• an understanding and appreciation of the cultures associated with the CLIL language

and the student's first language;

• the cognitive and social skills and habits required for success in an ever-changing

world.

The CLIL method can give young people the skills required to continue to study or work

in the CLIL language. However, language maintenance and learning is a lifelong

process requiring continued use and ongoing investment.

18