Helpful Hints – Lesson 14

advertisement

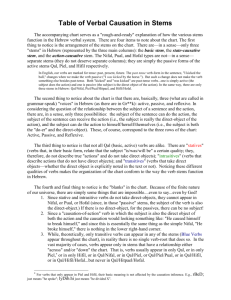

Helpful Hints – Lesson 14 This lesson is divided into three sections: 1) A discussion of the meanings of the 7 verbal "stems", 2) A list of the formation of the 7 verbal stems, and 3) A short discussion of how to do the "striptease" with Perfect verbal forms (i.e., how to recognize the stem forms, as well as the pronoun suffixes, as well as the three-consonant root....and put those three bits of information together to translate the meaning of the verb form) I won't spend any time on this in this "Helpful Hint". Paragraph 36: The meaning of the stems In the middle of page 108, Kelley gives a list of the 7 stems, both in English and in Hebrew. The best thing you can do initially is to just know the names of the 7 stems in the order he lists them here: Qal, Nifal, Piel, Pual, Hitpael, Hifil, and Hofal. (Notice that when I usually write the names, I leave out the ` [ayin] sign. It's no big deal.) So go ahead and know the names of these different formations in this order. After you have memorized the names of the stems in the right order, we can proceed..... The relationship between Qal and Nifal: The stems generally correspond to different types of "causation" in Hebrew. The two "base forms", Qal and Nifal, have no explicit causation; the subject of the verb either does the action (Qal) or is affected by the verb (Nifal). Whenever a verb appears in both Qal and Nifal—I can tell you—the verb in Qal will be a transitive verb. A transitive verb is a verb that can take a direct object. For example, the verbs "to create", "to make", "to write", "to give", and "to take" are all transitive...they all generally (but not always) have direct objects whenever they are used. (When I say, "God created", the natural question that usually is asked is "God created what?" When I say, "I gave" you naturally want to know what I gave. Transitive verbs most often have direct objects when they are used.) And verbs that are transitive will almost always appear in both Qal and Nifal. The verbs "to stand", "to be", "to live", "to lie down" are all intransitive ... they cannot take direct objects. (E.g., I can say "I took the book"....but, in English, if I say "I stood the book", people look at you funny.) So, in English, all transitive verbs can be both active (Qal, in Hebrew) or passive (Nifal, in Hebrew). We can say, "I created" and also "I was created". We can say "You made" and also "You were made". We can say "it wrote" and also "it was written". In the first cases, the subject is doing the action; in the second cases, the subject is affected by (or receiving) the action. That's the relationship between Qal and Nifal. The active/passive relationship is pretty standard in most languages....including our own English. The relationship between Qal and Hifil: Whereas Qal has no causation hinted in its form, Hifil implies a causation of an action: Someone is causing someone or something to do something. And (unlike with the Qal/Nifal relationship) it doesn't matter if the base verb is transitive or intransitive. For example, the sentence "I gave the book back" makes fine sense; likewise, the sentence "I made Noah give the book back" makes sense. Furthermore, the sentence "I stood" makes sense, as well as "I made Noah stand." Verbs that appear in both Qal and Hifil will, very often, be intransitive in their basic, Qal sense, but will be transitive (i.e., take a direct object) in their Hifil sense. For example, the verb "to burn"—in its base meaning—is intransitive: "Savonarolla, the martyr, burned at the stake"...meaning that he, himself, provided the fuel for a fire....there is no direct object. Notice that, in English, the verb is exactly the same in the sentence: "The Roman Catholic authorities burned Savonarolla." But in this last sentence, Savonarolla is the direct object of the verb. If we were to be totally explicit, we might rephrase this last sentence as, "The Roman Catholic authorities caused Savonarolla to burn." Here, in Hebrew, a Hifil verb form would be used. The relationship between Qal and Piel: Unlike Hifil (in which someone or something is being caused to do something), in Piel someone or something is being caused to be something. This relationship is usually the toughest for native English speakers to understand....usually because if we literally translate sentences governed by Piel verbs they sound incredibly awkward or just plain stupid in English. Very, very often when a verb appears in both Qal and Piel, we will choose another English verb to translate the sense (note the examples at the bottom of page 109). For example, I can say "I am big". If I put that simple statement in a Piel formation (along with a direct object), I would say "I caused Annie to be big"....which sounds really, really stupid. In English, to get the sense, I would more probably say something like "I reared Annie" or "I raised Annie", or "I brought Annie up". Likewise, I can say, "The car shines". In a Piel formation, I can also say, "I caused the car to be shiny"....or more probably "I polished the car". In translating Piel verbs, very often you will have to think about what the ultimate meaning of the verb is and then choose some other word (other than the base, Qal, vocabulary word translation) to translate it. Think for a moment about the simple act of driving a car down a street. In Hebrew, such a simple action can be thought of in all 7 stems: "I drive down the street." (Qal) "The car is driven down the street." (Nifal) "I cause the car to be moving," or, rather, "I drive the car." (Piel—the idea here is that the car is in a state of movement and that I'm causing it to be in such a state.) "The car is made to be moving," or, rather, "The car is driven" (Pual—the idea here is different than the Nifal, however. Here the moving state of the car is emphasized.) "I drive myself to the store." (Hitpael) "I cause the car to go," or, rather, "I drive the car." (Hifil—the idea here is different than the Piel, however. Here the action of movement is emphasized.) "The car is caused to go," or, rather, "The car is driven" (Hofal—the idea here is different than the Pual, however. Here the action is emphasized.) Pretty mind-bending stuff, huh? Making these semantic "pigeonholes" in your brain takes awhile...and seems terribly awkward and just plain irrelevant at first. I can tell you that the majority (not the vast majority...but the majority) of verbs you come across when you read will be the simple Qal forms. But being able to recognize when the Nifal, Hifil, and Piel forms are there....and doing so easily...will make translating much smoother and more interesting than simply relying on the NRSV, which mostly covers over the meanings of the stems so thoroughly that it is difficult to see any connection between the HB and the translation. OK...let's go over Kelley's discussion of these things.... The most important paragraphs on page 109 are those listed as (3) both at the top and at the bottom. In Nifal, Piel, and Hifil (on page 112), there will be some verbs that will not appear in Qal at all....they will only appear in Nifal....or in Piel/Pual....or in Hifil/Hofal. When verbs only appear in certain, non-Qal stems, Mr. Kelley will mark those verbs by putting them in brackets in his vocabulary list. On your cards, the stem will be noted in the translation on the back. In these cases, the way you memorize them will be the way you translate them; no mind-bending is necessary. For example, in the vocabulary list on page 126: ldB [ ] does not appear in Qal. It appears (almost exclusively) in Hifil and Hofal. You will memorize this word as "he separated, divided (something)". When you come across the word in the text of the Bible, don't screw up your mind trying to make it "causative of action" (i.e., don't translate it as "God caused the waters to divide something else". No, the way you memorize it is the way you will translate it: "God separated the waters.") vqB [ ] appears almost exclusively in Piel and Pual. So when you come across it in a reading, don't try to make it have a "causation of state". Saul does not "cause his fathers donkeys to be in a state of searching" (it even hurts my head to think about what that would look like!!). Saul, simply, "sought his fathers donkeys." rbD] appears, as Mr. Kelley tells you, only in Piel (therefore, it usually looks like: rBeDI). This word, along with rm;a' is one of the most common verbs of speaking in the [ HB. But don't be fooled into trying to make it a causation of state....it just means "he (or you, or I, or they, or y'all) spoke". One more note: starting with paragraph 36.5, Mr. Kelley throws out a lot of weak verbs. Don't freak out if you go through his explanation and the forms don't look the "way they are supposed to". I'll just note some of these characteristics of some of the verbs on Wednesday...but don't worry your head about them now. OK...let's talk a little about how these things are formed...paragraph 37: To get the entire perfect paradigm down (which, I can tell you, you will have to do for the final exam), you'll have to do three different things: 1) Know the Qal perfect paradigm....oh, you already know that! Excellent! 2) Know the 3ms form of each of the 7 stems, and 3) Know the prefix and (for Piel, Pual, and Hitpael) internal changes for the 7 stems. The 3ms forms of the 6 remaining stems are, relatively, easy to remember if you know the names of the stems: Qal: ¤¤;¤' ¤¤;¤.nI Nifal: _______________________________ Piel: Pual: ¤¤e¤i – with a dagesh in the middle "square"/letter ¤¤;¤u – with a dagesh in the middle "square"/letter ¤¤e¤;t.hi – with a dagesh in the middle "square"/letter Hitpael: ________________________________ Hifil: Hofal: ¤y¤i¤.hi ¤¤;¤.h' – that's a qamets-hatuf ("short U") under the prefix Notice that the name of the stem gives a good indication of the vowel pointing under the letters. Notice also that, with the exception of Qal (which you already know) all the "A class vowels" are short.....are patachs. Furthermore, all the "I class vowels" that occur in the last syllable (i.e., in Piel, Hitpael, and Hifil) are long (either sere or hireq-yod). OK...that's the 3ms form of the 7 stems. Once you know the 3ms form of the stems and the Qal perfect paradigm you can easily write the paradigm of most of the remaining stems (Warning: Hifil will be slightly different in 3 of the forms...but we'll deal with that later.) For all the stems, after you write the 3ms form, you will simply reproduce the rest of the Qal perfect paradigm, remove the qamets under the initial consonant and replace it with one of the following prefixes: ¤¤¤.nI Nifal: _______________________________ Piel: Pual: ¤¤¤i – with a dagesh in the middle "square"/letter ¤¤¤u – with a dagesh in the middle "square"/letter ¤¤¤;t.hi – with a dagesh in the middle "square"/letter Hitpael: ________________________________ Hifil: Hofal: ¤¤¤.hi – Also with a hireq-yod in the second syllable in 3fs and 3cpl (p.116) ¤¤¤.h' – that's a qamets-hatuf ("short U") under the prefix Notice some things about the way this is set up: There are three stems that don't have any prefixes: Qal, Piel, and Pual: rm;v'), Piel has an "I class" vowel under the first letter of the verb (rMevi), and Pual has a "U class" vowel under the first letter of the verb (rM;vu). 1) Qal has an "A class" vowel under the first letter of the verb ( 2) 3) Among those stems that have prefixes in the perfect forms: nI prefix Hitpael has a t.hi prefix (silent sheva) Hifil has a hi prefix, and Hofal has a h' prefix (qamets-hatuf). 1) Nifal has a 2) 3) 4) Although you may complain about the complexity of the meanings ("causation of state"/"causation of action"), you really can't complain about the complexity of the forms. They really are fairly self-evident, if you know their names. I hope this helps a bit. We will obviously be talking more about these things throughout the coming months.....