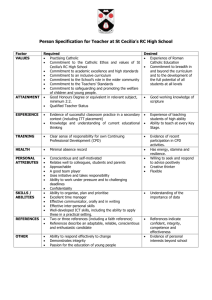

in knowknowing +... - Enseignement Catholique

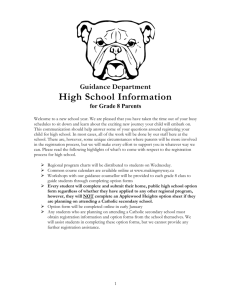

advertisement