country report - training.itcilo.it

advertisement

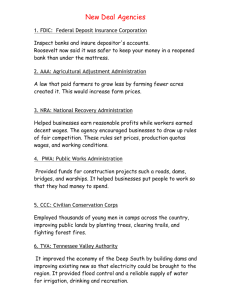

ILO-ACTRAV TRADE UNON TRAINING WORKSHOP ON INFORMATION TECHNOLOGIES WITH A FOCUS ON NETWORKS DEVELOPMENTS 11TH TO 15TH DECEMBER 2006, BANGKOK This paper aims to provide an overview on the changes in economic, industrial and labour policies in Malaysia due to the impact of globalisation and economic liberalisation, to assess the state of Malaysian trade unionism and finally, to examine the use/application of information technology within the labour movement in Malaysia. This paper does not purport to answer all questions but it will offer some views on the contemporary environment in Malaysia. However, these views are fully debatable and are open for discussion and further developments during the course of this program. Introducing Globalisation Let us start by saying that “Globalisation” is quite a complex and difficult subject to study because;1) There is no unique definition of the term – the meaning of globalisation varies according to one approaches the subject and even how one feels about it. 2) Globalisation is multidimensional – it involves many dimensions of reality, such as technology, the economic, politics, the society, culture and the environment 3) Globalisation is dynamic – it is still an ongoing process of economic internationalization 4) Globalization is a subject of ideological judgement – due to the complexity of the concept and its “openness” of its definition, this word is often misused. There are those who see globalisation as the source of any modern evil and those who think it to be the solution to any problem Each of us will define it according to our personal experience and local background. Nevertheless, globalisation is often described as, for example: Trade liberation (or Free Trade) Modernization Universalization Neo-Colonialism Race-to-the-bottom and etc. Where does the word “globalisation” come from? During the 1980s, the word “globalisation” appeared in the literature of America management schools in relation to the idea of the appearance of standardized system of production and thus of a homogenized market on a world scale. In 1991, the Oxford Dictionary of New Words recorded it officially for the first time as a word of common use to designate the interdependency between environmental problems and human activities. 1 When did globalisation begin? Under historical perspective, some see globalisation as a long-term process that goes in parallel with the history of mankind itself. According to this view, periods of geographical discoveries and intensification of international trade were the “ups” where the wars were the “downs” (period). Others authors argue that globalisation is peculiar to the 2nd World War aftermath and marks a world of dramatic transformation in international relations and technologies. They describe it as a world dominated by corporations and technologies, where governments have no real power. Some authors have termed 1990s as “Globalisation Thrust”. The pace of globalisation has accelerated over the past decade and a half because of development of new technology and reduced cost and speed of transportation. What are the main factors causing globalisation? The main point here is to identify which dimension (such as technology, economic, politics, the society, culture or the environment) plays the role of main globalizer. Some authors say that the most important role in triggering globalization was played by the rapid progress in the information and communication technologies which 1 offered new huge opportunities for economic profit and contacts with people (via email, stock exchange, online transfer and fast transportation). Others say that the main factor of globalisation was economy supremacy, especially to new productive strategies based on firms’ relocation processes on world scale pioneered by multinational enterprise (MNEs). Another view says that the main actor in the progress of the globalisation process in recent political decision-making. Accordingly to this view, globalisation is deliberately started by a large number of political subjects (governments, international organizations and MNEs) who took significant initiatives towards liberalisation, deregulation and privatization both at a national, regional and international level. In short, political decisions can start it, change it, slow it or even stop it. The current process of globalisation is often associated with a series of phenomena which are closely linked: A constantly growing interdependence and integration of the national markets Increased international trade and international exchanges of good and services Deregulation and opening up of the markets and economies, due to neoliberal government policies An accelerated development of the information technologies, expansion of 2 networks, and more generally speaking, the rapid development of new technologies due to microelectronics The creation of regional markets such as the EU, NAFTA, MERCOSUR. Regionalisation seems to be other aspect of globalisation The emergence of many economic poles which at the same time production centres – the US, Japan, Europe which on the one hand, attract direct investments and on the other hand, invest in foreign countries A new logic in connection with the spawning of multinational corporations, which is reinforced by the market integration, processes themselves. Changes in economic, industrial and labour policies in Malaysia In order to face the influence of rapid technological change, globalisation of products and markets, coupled with increased competition from other low cost Asian countries in the late 1980s; the Malaysian government introduced several economic policies, namely the “Look East” policy (1982) and the 2nd Export Oriented Industrialisation (EOI) strategy. The 1st EOI was launched in the 1970s to replace the “Import Substitution Industrialisation” (ISI) strategy, which started in the 1950s. These strategies were implemented to attract investors, namely foreign multinationals and firms and to gear towards exporting higher value-added electronics and electrical goods, as well as textiles and small manufactured goods. Many forms of incentives (financial, fiscal, regulatory and infrastructural) were introduced to attract foreign investors, particularly in the electronics and electrical goods sectors. Malaysia’s pursuit of open trade policies and its attractiveness to Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) have led to impressive economy growth and continued economic transformation. To continue wooing FDI’s; the government has reviewed its current policies on FDI’s in 2002 by way of introducing several incentives such as Investment Tax Allowance, Incentives for High Technologies Companies, Incentives for Strategic projects, Incentives for Small & Medium Size Industries, Investment Allowance and etc. Also as part of the liberalisation strategy, the Malaysian government has, since 1998, reemphasized its commitment to the deregulation and liberalisation of the financial sector. Prior to this, the Malaysia government prohibits the establishment of new banks and the expansion of foreign bank branches. Another aspect of globalisation is the changing position of women. The benefits and costs of globalisation and trade liberalisation are differentiated between women and men, as well as among different groups of women. Trade policies are viewed often discriminates against women. In the wake of the 1998 Asian economy crisis, coupled with the slowing inflow of FDIs into Malaysia over the past few years, the Government and employers are actively questioning the suitability of the current industrial regulatory arrangements. 3 Employers seeking for greater flexibility and less protection for labour, while the Government is questioning the appropriateness of the current labour laws for the achievement of its economic development goals and want a more liberal industrial relations regulatory system. There seems a serious lack of urgency to look into the welfare of workers in Malaysia in facing the problems arising from the accelerated pace of globalisation and economic liberalisation policies. According to Prof. V.Anantaraman (1997), in Malaysia, trade union and workers rights are seen as subordinate elements to the greater goal of economic development of the country. The government’s policy towards labour, therefore, is geared to controls workers organizations rather than to enlist their cooperation in the effort of the nation becoming a fully industrialized country in 2020. The 1959 Trade Union Act (TUA) is the government’s principal means of controls over the activities of trade unions. It is done by laying down rules and regulations which unions are required to follow. Another employment-related legislation is the 1967 Industrial Relations Act (IRA). Its primary aim is to create a comprehensive statutory framework for the orderly conduct of Labour Management relations. It deals in detail with the right of workers and employers and their organizations, recognition to trade unions by employers, collective bargaining, the settlement of labour disputes as well as strikes and lockouts. These legislations have been amended a number of times, mostly at the expenses of trade union development, on the ground that industrial growth would eventually lead to diminishing social tensions arising out of exploitation of labour. The Director-General of Trade Union (DGTU) and the Minister of Human Resources, both government officials, have enormous discretionary powers to regulate trade union affairs. Thus, there are extensive debate on the possible misuse and abuse of these powers vested in the Director-General. The main challenges confronting the Malaysian labour movement include declining trade union density, outsourcing/sub-contracting, unfavorable national labour laws, import of cheap labour, on-going process of restructuring, mergers and acquisition and constant down-sizing which have led to deteriorating employment, working and living conditions. Declining Trade Union Density Malaysia has a low trade union density. In 1983, about 15% of the employees in the country were unionized. However, the position of organized labour further deteriorated to approximately 9% in 2003. There is little evidence to suggest that the situation has changed as evinced by the total number of unionized workers in the country as at 2004, which were only 783,108 or 7.91% of the total workforce of 9.9 million. 4 Union organizer’s efforts to increase union memberships have been restricted by Section 9 (1) of the Industrial Act 1967 which does not allow employee working in managerial, executive, confidential staff and security capacities to join Unions. Meanwhile, employers often interpret the managerial and executive category to include supervisors, assistant supervisors, section leaders and lower level supervisory personnel. There has also been tendency to consider all workers in information technology as being in the “confidential” category, which effectively prevents them from joining trade union. Unfavorable National Labour Laws Workers in Malaysia continue to be denied their rights to join a trade union of their choice, and to freely organise and bargain collectively because of government policy, restrictive legislation and bureaucratic practices. A decision by the ILO Committee on Freedom of Association (CFA) in 2004 found many provisions of the 1959 Trade Union Act violate the principles of freedom of association. MTUC (2004) highlighted that in the last 4 years, many employers have denied workers the right to join a union and collectively bargain for better terms and conditions. MTUC cited that after 47 years of Merdeka, workers are not given the freedom to join a union of their choice as guaranteed under Article 10 of the Federal Constitution. The national congress further reiterated that in the last 3 years the HR Ministry has denied freedom of association to more than 8,000 workers in manufacturing companies. There are many restrictions and obstacles on union formation while the procedure for obtaining union recognition is lengthy and cumbersome. The DGTU has discretionary power to refuse to register a trade union and to withdraw registration, without giving any reason for such decisions. The Ministry of Human Resources may also suspend a trade union up to 6 months in the interest of national security or public order. In the year 2000 – 2003, a total of 53 unions were deregistered. Half of these were deregistered because they failed to meet their obligations under the Trade Union Act. The most publicized example of a union being deregistered for unlawful activities is the Airlines Employees Union (AEU) for organizing illegal strike in 1979. Trade unions whose registration has been denied or withdrawn are considered as illegal association. The 30-year ban on the formation of an independent (national) industrial union in the electronics industry remained in force. According to Prof V Anantaraman, the fear that unionization of electronic workers may disrupt Government industrialisation strategy prompted the Government to prevent it at any cost. As the result, some 160,000 workers employed by multinational companies have been denied the right to form and join a national union in the electronics industry. They can only form inhouse unions. 5 The prospects of unionization of electronics workers is in fact bleak unless the electronics workers, mostly women in each of the electronic establishment take upon themselves the formidable task of forming in-house unions in the face of intimidation and threats of dire consequences by the employer, mostly large multinational corporations. Migrant workers In the name of globalisation, an ever-increasing number of employers, including large multinational corporations, are turning to foreign and contract workers. MTUC (2004) cited that contract workers have no security of tenure or social protection (via EPF and SOCSO). In Malaysia, foreign workers are barred from trade union membership, although the law merely says that only Malaysian can hold union office. One of the conditions imposed on work permits issued to foreign workers by the authorities have effectively prohibited them from joining unions. In many companies, foreign workers constitute as much as 30 to 40 per cent of the workforce. MTUC (2004) cited that foreign workers are often paid less and unscrupulous employers unfairly terminate many foreign workers prior to expiry of their contract. Most foreign workers work long hours, for very low pay and are often subject to verbal and physical abuse. MTUC highlighted a case of 90 Vietnamese who were abandoned and forced to eat cats and dogs. They were subsequently sent back at Government’s expenses. Discriminatory practices against women Despite having provisions to ensure equality for women, many companies including large multinational corporations discriminated female workers to low wages, marginalization and poor working conditions. Women are frequently the main targets of anti-union hostility, notably in the electronics industry. In the Malaysia Airlines System (MAS) female members of the cabin crew are required to retire in attaining the age of 40 years and for senior staff at 45 years whereas male counterparts are allowed to work until 55 years. While there are more women joining unions, they are under-represented in membership levels and in particular in decision-making structure. Women are also almost invisible among the higher ranks of union officials. Others Challenges MTUC received many complaints from affiliates regarding employment of foreign workers and also discriminatory practices against Malaysians workers. In the wake of the Asian economic crisis in 1998, thousands of jobs were loss resulting from company closure, factory relocation and mergers of banks. 6 The Government policy on recruitment of foreign workers has created a great deal of anxiety amongst Malaysians. The situation is worsening as employers have also resorted to other threats such as outsourcing, voluntary separation scheme (VSS), special separation packages (SSP), job-sharing, contracting and employing part-time workers. Part 2 State of the Trade Unions – Extent of unionization, number of national centres, structure and organization of trade unions, main challenges facing the trade union movement in the field of – organizing, trade union education, communication, campaigns, etc. There are two (2) national labour organizations in Malaysia. The MTUC is a society of trade unions in both the private and government sectors and is registered under the Society Act. The other national organization is the Congress of Unions of Employees in the Public and Civil Service (CUEPACS), a federation of public employee unions registered under the Trade Union Act. Congress of Unions of Employees in the Public and Civil Service (CUEPACS) CUEPACS is a federation of trade unions of government workers. It was registered in 1959. Membership is open to all registered trade unions in the public and civil services in West Malaysia. The administration of CUEPACS is carried out by a council elected at a convention held once in three (3) years. Malaysia Trades Union Congress (MTUC) MTUC is the oldest National Centre representing the Malaysian workers. It came into existence at a time when the First Emergency was declared against insurgent communist activities in 1948. Owing to the ban on forming general confederations of trade union, the MTUC was registered under the Registration of Societies Act, not under Trade Unions Act of 1959 (i.e. because of dissimilarities of its affiliates). Therefore, the MTUC does not have the rights to conclude collective bargaining agreement, nor to undertake industrial actions, but to provide advisory and technical supports to its affiliates. Members of the MTUC are individual trade unions from all major industries and sectors with approximately 500,000 members. MTUC represent about 250 unions, most of which were unions from private sectors. 7 Although the key positions of the MTUC in representing workers’ interest have never been denied, it has never had the total support of all employees’ unions. At various times, some of the strongest affiliates left the MTUC because of dissatisfaction with its leadership, policies or its weak financial position in representing workers’ and unions’ interests. Nevertheless, the MTUC continued to be recognised by the Government as the representative of workers in Malaysia and is consulted by Government on major changes in labour laws through the National Joint Labour Advisory Council (NJLAC). MTUC also represent labour at the International Labour Organization (ILO) conferences and meetings According to the annual report of the Ministry of Human Resources for the year 2004, there are a total of 611 registered trade unions for workers in Malaysia. Of these, 380 unions represent 418,381 privates’ sector workers, 130 unions represent 296,139 public sector workers while 101 unions represent 68,588 statutory and local government workers. The total number of unionized workers in the country was 783,108 or 7.91 per cent of the total workforce of 9.9 million. Organizing Organizing the unorganized is one of the most important issues to the trade union movement in Malaysia as only about 9% of workers are organized. It means that a significant segment of the working population was not organized, including foreign workers. Therefore, it is important for the unorganized secure union recognition. Under Section 9 of the Industrial Relations Act, union recognition claims should be settled within 21 days but in reality, this takes much longer if a dispute occurs, as it gets taken to the Director General of Industrial Relations (DGIR), the DGTU, then to the Minister of Human Resources, who has the final say, unless that is challenged in the High Court. The High Court is fairly limited, in practice, in its ability to overturn a previous decision. It is not uncommon for recognition claims to take between 18 to 36 months to settle, particularly if an employer is using unfair tactics to prevent them getting recognition. It must be emphasized that the government fails to implement the power its already has to speed up union recognition. If an employer fails to grant recognition o a union within 14 days of notification by the DGIR, the Minister of Human Resources has the power to make a final decision to order the employer to recognize the union, but reluctant to do so. At the end of 2005, MTUC has recorded 25 cases in which the DGTU had arbitrary refused union recognition. In some cases, the Minister also failed to issue a recognition order. Some companies are proactive in their attempts to prevent their workers joining trade unions, by taking numerous steps to reduce or eliminate the need for their workers to form and join unions. Meanwhile, in general the government’s policy is to encourage the formation and growth of in-house unions. 8 Amendments to the Trade Union Act 1959 allowed for the formation of in-house unions, regardless of whether a registered national union already existed. The national trade union movement has strongly opposed the establishment of in-house unions because “more unions mean more fragmentation and weaker unionism. Government policy prohibited the formation of national unions in the electronics sector, the country largest industry. According to MTUC, 160,000 electronic workers were unable to organize, and only 8 in-house unions were formed in the electronics industry. The question of which type of union, in-house or national, can get better benefits for its members is still unanswerable as there is no data on this debate. Trade union education Trade unions in Malaysia are generally constrained by the lack of funds to carry out all their intended programmes. Therefore, education tends to be neglected by individual unions. Therefore, other than carrying out research on matters of trade union interest, the MTUC also provide trade union education programmes. It runs training programmes to help union leaders from its affiliates to understand their roles and responsibilities. Leadership In Malaysia, younger group do not take much interest in trade union. Trade unions no longer attract youngsters as there is no career and not professionally attractive to them due to the following reasons:-. (a) Leadership is confined to working employees, in similar trade (b) Union leadership held for short tenure by working employees as their have their own career in the Enterprise (c) Trade unions do not pay salaries for their leaders and attract talents 9 Part 3 Description of the use/application of information technology within their trade union and within the labour movement in their country, including ‘needs’ identification in the context of IT. It is interesting to note that there is about 2,700 trade union websites now exist worldwide. However, the use of information technologies by trade unions in Malaysia is still very limited. According to the MTUC, less than 50 of its affiliates have website. Overall, trade unions in Malaysia are slow to react to the potential of the Internet as a medium to organise, campaign and communicate with members and others who are interested in the Union’s information and views. What are the obstacles and challenges faced by the local unions to re-invent themselves as e-organisations? Some of the main ones will be the following : Language i.e. English vs. own national language (Bahasa Malaysia) Many individual members do not have access to an Internet terminal. Investments in ICT are too expensive Low commitment from the leadership for IT strategy How ICT can be used to benefit trade unions, based on some specific examples of relevant activity by my own union the Association of Maybank Class One Officers (AMCO – www.amco.org.my)) and the MTUC ICT improved internal communications and transactions. My union now issues agendas, paper and minutes of Executive meetings in electronic form. ICT improved external communications and transactions. My union website enables me to communicate directly with individual members. The next stage of improvement is to make my Union website more personalized and interactive. By personalized, I mean that a member will be welcomed by name while by interactive, I mean that to host discussion group or M2U (member-to-union) to discuss on issues of current interest or controversy in the union. 10 Membership activities – organizing, recruiting and servicing individual members. As a staring point, my Union website only enable one to register an interest to join. The next stage of improvement will be to enable electronic registration for membership. To make greater use of the electronic organizing to communicate with the potential members (i.e. the unorganized) if we can obtain their email addresses. For my union, I wish to take my Union website to the next level; namely ; On line ballots [with password to protect ballot paper] Conduct surveys E-campaigning Registration for courses organized by my Union should be electronic and confirmation of registration should also be electronic. Conclusion Overall, trade unions cannot afford to ignore ICT, as it will profoundly influence union activities. Unions need to become more flexible, more inventive and more modern to respond effectively to the threats and opportunities that it faces with the growing influence of MNCs and the growing numbers of bilateral trade agreements. References Anantaraman, A (1997) Malaysian Industrial Relations: Law & Practice, Universiti Putra Malaysia Press Serdand, Malaysiaa Ramasamy, Nagiah (8th -10th June 2004), Shaping The Future of Trade Unions In A Rapidly Changing Working Environment, presented at Sheraton Hotel, Kuala Lumpur in 2004 for MTUC/ILO/ACTRAV Malaysian Trade Union Congress (MTUC), www.mtuc.org.my/policy_mtuc.htm Aminuddin, Maimunah (5th Edition, 2006), Malaysian Industrial Relations and Employment Law, Mc Graw Hill Education, Malaysia Actrav – Globalisation (Module) From MTUC 11