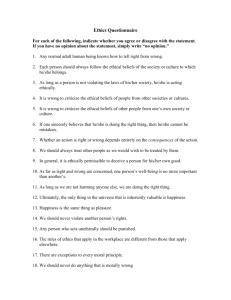

chapter 3 - University of Bath

advertisement