A. Serious Games

advertisement

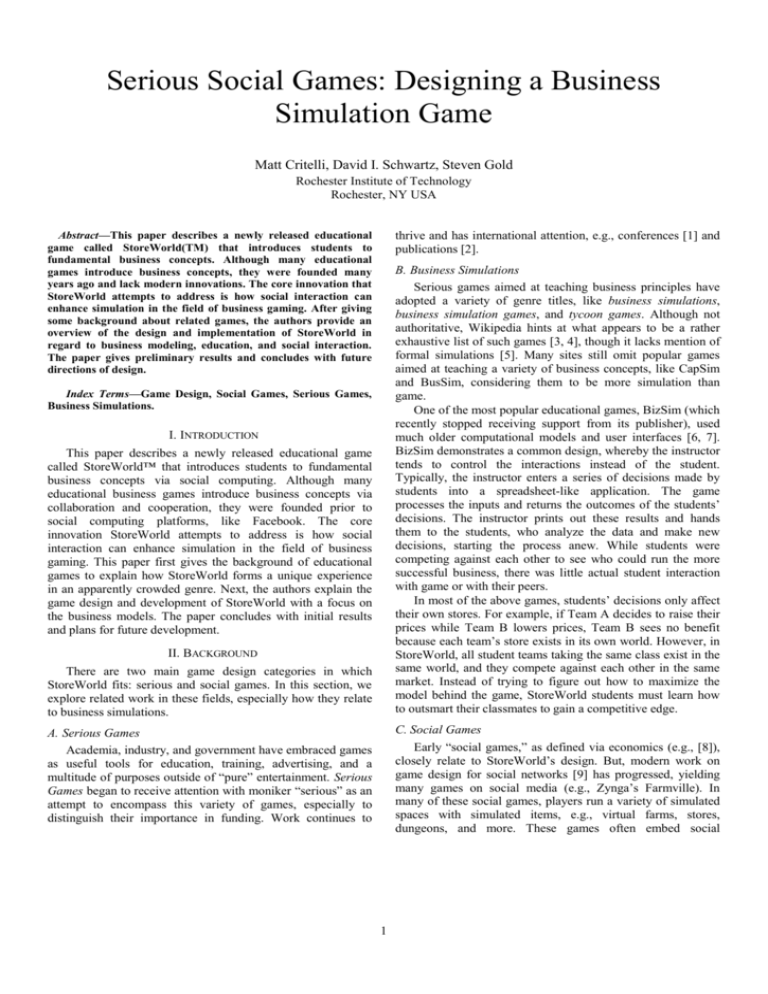

Serious Social Games: Designing a Business Simulation Game Matt Critelli, David I. Schwartz, Steven Gold Rochester Institute of Technology Rochester, NY USA thrive and has international attention, e.g., conferences [1] and publications [2]. Abstract—This paper describes a newly released educational game called StoreWorld(TM) that introduces students to fundamental business concepts. Although many educational games introduce business concepts, they were founded many years ago and lack modern innovations. The core innovation that StoreWorld attempts to address is how social interaction can enhance simulation in the field of business gaming. After giving some background about related games, the authors provide an overview of the design and implementation of StoreWorld in regard to business modeling, education, and social interaction. The paper gives preliminary results and concludes with future directions of design. B. Business Simulations Serious games aimed at teaching business principles have adopted a variety of genre titles, like business simulations, business simulation games, and tycoon games. Although not authoritative, Wikipedia hints at what appears to be a rather exhaustive list of such games [3, 4], though it lacks mention of formal simulations [5]. Many sites still omit popular games aimed at teaching a variety of business concepts, like CapSim and BusSim, considering them to be more simulation than game. One of the most popular educational games, BizSim (which recently stopped receiving support from its publisher), used much older computational models and user interfaces [6, 7]. BizSim demonstrates a common design, whereby the instructor tends to control the interactions instead of the student. Typically, the instructor enters a series of decisions made by students into a spreadsheet-like application. The game processes the inputs and returns the outcomes of the students’ decisions. The instructor prints out these results and hands them to the students, who analyze the data and make new decisions, starting the process anew. While students were competing against each other to see who could run the more successful business, there was little actual student interaction with game or with their peers. In most of the above games, students’ decisions only affect their own stores. For example, if Team A decides to raise their prices while Team B lowers prices, Team B sees no benefit because each team’s store exists in its own world. However, in StoreWorld, all student teams taking the same class exist in the same world, and they compete against each other in the same market. Instead of trying to figure out how to maximize the model behind the game, StoreWorld students must learn how to outsmart their classmates to gain a competitive edge. Index Terms—Game Design, Social Games, Serious Games, Business Simulations. I. INTRODUCTION This paper describes a newly released educational game called StoreWorld™ that introduces students to fundamental business concepts via social computing. Although many educational business games introduce business concepts via collaboration and cooperation, they were founded prior to social computing platforms, like Facebook. The core innovation StoreWorld attempts to address is how social interaction can enhance simulation in the field of business gaming. This paper first gives the background of educational games to explain how StoreWorld forms a unique experience in an apparently crowded genre. Next, the authors explain the game design and development of StoreWorld with a focus on the business models. The paper concludes with initial results and plans for future development. II. BACKGROUND There are two main game design categories in which StoreWorld fits: serious and social games. In this section, we explore related work in these fields, especially how they relate to business simulations. C. Social Games Early “social games,” as defined via economics (e.g., [8]), closely relate to StoreWorld’s design. But, modern work on game design for social networks [9] has progressed, yielding many games on social media (e.g., Zynga’s Farmville). In many of these social games, players run a variety of simulated spaces with simulated items, e.g., virtual farms, stores, dungeons, and more. These games often embed social A. Serious Games Academia, industry, and government have embraced games as useful tools for education, training, advertising, and a multitude of purposes outside of “pure” entertainment. Serious Games began to receive attention with moniker “serious” as an attempt to encompass this variety of games, especially to distinguish their importance in funding. Work continues to 1 interactions by having other players help manage these virtual spaces, purchase items, and communicate. m=p*a*q*b (1) where the variables are defined as follows: D. Serious Social Games Early “social games” studied the Prisoners Dilemma for competition of resources [8]. Related work attempts to bridge game theory with game design theory [10]. Whereas many social games provide basic concepts of business (e.g., Farmville), most of the educational business simulations were developed prior to the social computing revolution. StoreWorld (Fig. 1) combines social computing to facilitate recent explorations of social and serious games. III. DESIGN Investigating Farmville, Roller Coaster Tycoon, and many other business simulations, the StoreWorld design team initially wondered how to modify a common virtual store concept with actual business models. But, unlike more established games developers prior to social computing, StoreWorld would work via a social computing platform. Thus, the team could make a social, serious game that teaches introductory business concepts in an environment that already facilitates the multiplayer aspects of an online community. The process involved a large degree of iteration, especially given the need to define levels of abstractions of business decisions. The social aspects of StoreWorld are indeed common aspects of social game design: players build virtual stores, sell virtual clothes, and hopefully make sufficient profit to continue to stay in business. However, the rules guiding the business decisions use real business models, as discussed below. m: demand for the specified item in the given store. p: price rating compared to other stores selling this same item. a: attraction of the given store’s customers to this item, e.g., if the store’s customers want punk-style clothing, they will not be interested in a sports t-shirt. q: store’s quality as determined by the store’s decor, quality management, and number of employees. b: store’s level of advertising. The software calculates each variable with Eq. 1, which results in a logistic curve to simulate diminishing returns: 1 (2) -8(x-0.4) 1 2.7182 where x is a value between 0 and 1. Equation 2 generates the values multiplied together in Eq. 1, which results in the market demand for the given store. This demand is then taken and compared to the demand for the same item in all of the other stores in a class, resulting in a final per-item market share. The market share describes the maximum number of sales per-item that a store could make. The game uses this number to determine how many AI shoppers to spawn and enter a player’s store. From here, specialized searching routines make the shoppers walk around the player’s store in a realistic manner while they search for items they want to buy (Fig 1.). Each shopper is created with certain likes and dislikes, as well as a certain income level modeled after real-world income brackets to ensure proper distribution of money among shoppers. These factors determine the items shoppers want to buy and how many total items they can purchase before they must leave the store. Thus, students must not only manage their store’s pricing, advertising and quality well, but they must also design their store’s layout so that items are easy to find. Our model also keeps track of lost sales and market saturation. Lost sales happen when a store fails to meet its demand, usually by running out of inventory. This overflow pools on a per-item basis and then redistributes to the other stores in the class, allowing competing stores to “steal” sales from their unprepared competitors. The game also tracks the total sales of an item. In about one year of in-game time, the market saturates. Thus, players must to keep track of what their competitors sell if they want to avoid fighting over an already saturated market. Figures 2-5 show a variety of financial statements and reports the teams use to run their stores. For products other than clothing, a new model would need to be created. However, thanks to the game’s architecture (discussed in Section IV), changing models is relatively painless. StoreWorld could easily support a different type of retail environment (like an electronics store instead of a clothing store) or even an entirely different type of business (like a restaurant) with a new model. A. Business Models The economy in StoreWorld is driven by the Bass diffusion model, which describes the rate at which a product is adopted by consumers over time [11]. StoreWorld adapts the Bass model, created from a series of Bass model equations and tailored for the specific characteristics of the game. The game uses this model to determine the demand for each item on a per-store basis, as described by Eq. 1: Fig. 1. A player’s store in StoreWorld 2 Fig. 2. Income statement Fig. 4. Balance sheet Fig. 3. Cash flow Fig. 5. Loans B. Social Interaction Players work on teams of one-four players that control a single store. By using on-line and off-line communication, each team coordinates the store creation, customization, purchasing, pricing, and all other business decisions. The game facilitates on-line communication via a virtual plaza to provide a common meeting place for all teams. Besides inter-team communication, every player receives a “stipend” from their sales, which they can use to purchase clothes from other stores to dress their avatars and investigate the competition. For example, players might wish to show off their avatars in the common plaza, which helps to increase player engagement. The game also expands upon player interaction via leaderboards that show sales rankings and profits. IV. IMPLEMENTATION StoreWorld currently exists on Facebook and will be open for external play as of the publication of this paper. The code is currently closed, but it may become open source at some point in the future. There are two main components to StoreWorld: the server package and the game client. The client is written in ActionScript3 and deployed using Flex to Facebook, allowing anyone with an active Facebook account to play. The client handles displaying the game and allowing the user to interact with their store. Using this client, players will purchase inventory, design their store, view financial reports, and carry out many other operation tasks. The client also handles the searching routines for the AI shoppers. The server handles 3 most of the business model simulation, which helps to ensure that the data used to create the market has not been tampered with and keeps the database secure. StoreWorld’s server package is built on a LAMP stack (Linux, Apache, MySQL, PHP). A MySQL database stores all of the information used in the game, including the clothing catalog, all store information, and numerous data logs. A series of PHP scripts handle communication between the client and server, ensuring the game never connects directly to the database. These PHP scripts also handle the large amount of calculations that need to be done to fulfill our business model. Upon completion, most scripts return an XML document that is then sent back to the client to be parsed. StoreWorld also a smaller, third component: the admin client. Instructor will receive access to the admin client, which allows the following: teach concepts about management. Moreover, allowing players to work in stores could create networking for outreach, as in college students managing high school students. The business models need continued testing given their complexity. By adding in different goods, more complexity in the stock market, utilities, and a multitude of other factors, the game could eventually expand into exploring economic issues. For example, in addition to fashion, players might sell cloth, hire designers, and manage delivery, each of which tapping into other business models. Eventually, StoreWorld might encompass a variety of businesses and markets. VII. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The authors are deeply appreciative of the funding provided by an RIT Trustee grant from Don Truesdale and additional funding from RIT’s E. Philip Saunders College of Business. StoreWorld exists because of our colleagues Ashok Rao, Erik Vick, Bob Boehner, Jason Arena, Richard DeMartino, and the multitude of RIT students from across the Schools of Interactive Games and Media, New Media Interactive Design, and Business who created StoreWorld. Finally, we are indebted to the School of Interactive Games and Media and the Department of New Media Interactive Design for providing laboratory space. setup new classes within the game. set certain game variables (like market growth/decay rates and periods). pause the game for a class (meaning that no stores will be able to sell items to shoppers, but students can still access the game). allow the instructor to view all of the information for each store in their class, which they can use to help students perform better and assign grades. VIII. REFERENCES [1] Serious Games Summit, www.gdconf.com/conference/ sgs.html, accessed August 6, 2012. [2] D. Michael and S. Chen, Serious Games: Games That Educate, Train, and Inform, Course Technology PTR, 2005. [3] List of Tycoon Games, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/ List_of_Tycoon_games, accessed August 6, 2012. [4] Chronology of Business Simulation Games, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chronology_of_business_simulation video_games, accessed August 6, 2012. [5] Gaming/Simulation Packages and Books by ABSELites, absel2011.wordpress.com/gaming-packages-by-abselites/, accessed August 6, 2012. [6] BizSim, www.phronetix.com/bizsim/index.html, accessed August 6, 2012. [7] J. L. Casti, “BizSim: the world of business – in a box,” Artificial Life and Robotics vol. 4:3, pp. 125-129, 2000. [8] G. Abramson and M. Kuperman, “Social games in a social network,” Physical Review E, vol. 63, pp. 030901-1—030901-4. [9] A. Järvinen, “Workshop: game design for social networks,” MindTrek ’09: Proceedings of the 13th International MindTrek Conference: Everyday Life in the Ubiquitous Era, pp. 224-225. [10] D. I. Schwartz and J. D. Bayliss, “Unifying Instructional and Game Design,” in Handbook of Research onImproving Learning and Motivation through Educational Games, P. Felicia (ed), pp. 192-214, 2011. [11] The Bass Model, www.bassbasement.org/BassModel/, accessed August 6, 2012. [12] StoreWorld™, apps.facebook.com/storeworldgame, accessed August 6, 2012. [13] Imagine RIT: StoreWorld, www.democratandchronicle. com/VideoNetwork/1617948363001/Imagine-RIT-Storeworld, accessed August 6, 2012. The admin client is currently separate from the game client, meaning the instructor does not need a Facebook account to use the game in their classroom. StoreWorld has been designed to be as secure as possible. Since teachers may use this game to determine student grades, the design team ensured that students cannot tamper with any data to give themselves an unfair advantage. All data received from the client is checked and verified before being used in calculations or stored in the database to ensure it is true, unaltered data. V. CURRENT RESULTS StoreWorld [12] has had a series of focus groups of different undergraduate computing students and exposure to the public via showcase events. Early results showed that the single-player experience was indeed expected: it was brief and somewhat undirected. However, once development of social interactions became more fleshed out, reactions became more positive, especially during public testing [13]. As of the development of this paper, StoreWorld continues to be tested. VI. FUTURE DIRECTIONS StoreWorld has a formal release for a class of introductory business students as of the release of this paper. As with all game development, the process dictated that a variety of features had to wait. For example, the integration of a “newspaper” (i.e., “StoreNews”) could serve to provide avenues for teams to advertise, especially to help engage players visually. With advertising and an enhanced employees system, players could hire other players, which would help 4 5