The Protection of Elder Abuse under the Criminal Code

advertisement

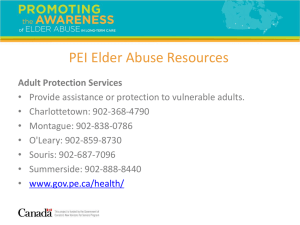

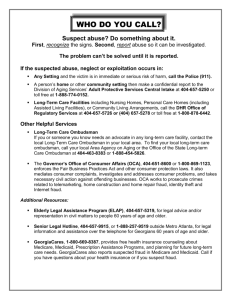

The Protection of Elder Abuse under the Criminal Code Foreword This submission is in response to the paper by the Office of the Public Advocate and the Queensland Law Society, Elder Abuse: How well does the law in Queensland cope?1 (‘the Paper’). The Paper takes the stance that the current legislative protections in Queensland surrounding elder abuse lack stipulations needed to properly protect this vulnerable, yet large portion of the community; that given the nature of elder persons, there needs to be a narrower legislative approach protecting specific elder abuse offences, mirroring legislation in place in the USA. The paper also suggests that the duty to provide necessaries of life under the Queensland Criminal Code2 should be amended to include a duty between adult children in relation to their dependant parents3. Summarily, the paper argues that Queensland legislation and the Common Law fail to address the particular vulnerability of older persons where there are circumstances such as dependence, frailty, immobility and impaired capacity4. In light of these suggestions, the following submission offers a qualification to the paper, from a legal perspective, that all forms of elder abuse are adequately covered by the Queensland Criminal Code. A comparative analysis of United States, and in particular, Californian elder abuse laws will be undertaken to determine how effective the specific legislation has been within their jurisdiction. 1. Analysis It is widely accepted that elder abuse commonly involves physical, sexual, financial, psychological abuse and/or neglect5. The societal concern seems to be 1 The Office of the Public Advocate and The Queensland Law Society, Elder Abuse: How well does the law in Queensland cope? (2010). 2 1899 (Qld). 3 The Office of the Public Advocate and The Queensland Law Society, Elder Abuse: How well does the law in Queensland cope? (2010) at 8.7. 4 The Office of the Public Advocate and The Queensland Law Society, Elder Abuse: How well does the law in Queensland cope? (2010) at 8. that since there is a growing proportion of Australia’s population that will qualify as being elder in a broad sense of the word, we need to address the consequential increases in cases of elder abuse, ahead of time. There only exists a vague definition of who constitutes an ‘elder person’. The fact that the term is not uniformly defined seems to be a contributing reason as to why some are of the view that elder people are un-protected – while the group cannot be properly defined, legislation cannot categorically protect them. However, by virtue of the fact that those persons the most at risk of elder abuse, tend to be older people who have impaired capacity, the majority of elder persons at high risk are covered by the provisions of the Criminal Code aimed at protecting the mentally impaired. From a legal perspective, it is unnecessary to legislate specifically for those people who fall under the category of being an elder, when regardless of a person being old in terms of chronological years, or physical or mental state, each of the offences which are thought to be specifically prevalent in circumstances of elder abuse, are already covered by the Criminal Code. Physical abuse Physical abuse amounts to assault and is unlawful under section 2456 of the Code. The offence of assault criminalises actual physical, threatened or attempted application of force in any way that may cause injury or discomfort7. While this section makes no reference to the term elder abuse specifically, physical abuse of an elderly person is none-the-less protected. 5 The Office of the Public Advocate and The Queensland Law Society, Elder Abuse: How well does the law in Queensland cope? (2010) page iii; The Australian Network for the Prevention of Elder Abuse, Preventing elder abuse in an aging world is everybody’s business (2007) <http://agedrights.asn.au/pdf/ANPEA%20Brochure%20June%2007.pdf> at 7 March 2011. 6 Criminal Code 1899 (Qld) s245(1). 7 M J Shanahan et al, Carter’s Criminal Law of Queensland (Butterworths, 2005) 475. A key concern for advocates of elder abuse legislation is that provisions do not take into account the particular vulnerability of elderly people8. However, the Code in conjunction with the Common Law mitigates this vulnerability in terms of sentencing. It is an aggravating circumstance where the victim of an assault is an elderly person9, and tends to invoke harsher sentencing. Crimes involving violence or the threat of violence towards an elderly or disabled person are especially abhorrent to the Australian community, and as such, are considered to be crimes of a more serious nature10. Section 216 of the Code criminalises the abuse of persons with impairment of the mind. It is an offence under the act to “… indecently deal with a person with an impairment of the mind”11. In this section, “deals with” includes any act that, done without consent, would constitute assault12. This provision identifies the mentally impaired as particularly vulnerable. It also specifically deals with the situation where the abuser is a guardian of the mentally impaired victim – acknowledging the potential for abuse of power where an offender holds such a relation with the victim, by significantly increasing the sentencing provisions13. In the case of an elderly person with mental impairments being physically assaulted, section 216 as well as the consideration of aggravating factors in sentencing (such as age, or the relation of the offender to the victim), highlight the extent to which Queensland criminal law already protects the vulnerability of our elders to physical abuse. Elder abuse legislation against physical abuse is not necessary as the particular heinousness of these types of crimes is already recognised under the law in Queensland. 8 The Office of the Public Advocate and The Queensland Law Society, Elder Abuse: How well does the law in Queensland cope? (2010) at 4.1.1; 4.2.2 and 4.4. 9 R v Laing [2008] QCA 317. 10 Re Darin Rosson v Minister for Immigration and Citizenship [2010] AATA 880 at 23. 11 Criminal Code 1899 (Qld) s216(2)(a). 12 Criminal Code 1899 (Qld) s216(5). 13 Criminal Code 1899 (Qld) s216(3) & (3A). Sexual abuse Sexual abuse is extensively covered in the Code. Section 352 covers sexual assault generally, while sexual assault against an elderly person is an aggravating factor to be considered in sentencing14. It is an offence to sodomise, or to be sodomised by a person with a mental impairment15. This would include elderly people with aged related mental impairment. If the offender is a guardian or lineal relation of the impaired person, additional sentencing provisions under this section increase the maximum penalty to life imprisonment16. While elder person is not specifically referred to, the section protects against any situation where a mentally impaired elderly person might be sodomised. In a different circumstance of sexual abuse against an elder, where the elder person is not mentally impaired but is coerced into indecent or sexual acts by means of their dependency on the person coercing them, particular provision is set out in section 21817. The position of power that a guardian or family member on whom an elder might be dependant is of particular concern for elder abuse advocates18. The section states that a person who “by threats or intimidation of any kind, procures a person to engage in a sexual act...commits a crime”19. Intimidation or threat of “any” kind, includes a threat to abandon, to assault or to neglect. Another inadvertent protection against sexual abuse of elders is in the case of incest. Where consent is given by an elder person to carnal knowledge by a family member, the abusing relative cannot use the consent as a defence20. This 14 R v Roberts and Roberts [1982] 1 WLR 1 33; [1982] 1 All ER 609; (1982) 74 Cr App R 242. Criminal Code 1899 (Qld) s208(1)(c)&(d). 16 Criminal Code 1899 (Qld) s208(2)(b). 17 Criminal Code 1899 (Qld) s218. 18 The Office of the Public Advocate and The Queensland Law Society, Elder Abuse: How well does the law in Queensland cope? (2010) at 3.2. 19 Criminal Code 1899 (Qld) s218(1)(a). 20 Criminal Code 1899 (Qld) s222(3). 15 means that regardless of if the elder person consents either by coercion or due to mental impairment, the abuser is guilty of a crime21. Extended sentences are allowed for those who sexually abuse from a position of guardianship, if the victim is mentally impaired22. And in the circumstance of rape23, again it is an aggravating factor if the victim is elderly24. Financial exploitation The Paper refers to financial exploitation/abuse where an elderly person, who has lost (or is losing) capacity, is manipulated or deceived into signing documents, selling property or passing on Enduring Power of Attorney25. The Code criminalises dishonestly obtaining advantage or benefit, pecuniary or otherwise from another person26. In R v Naidu27, the Court was inclined to give harsher penalties to the Appellant in light of the fact that the man whom the Appellant defrauded was an older person who had, at the time of being defrauded, lost his capacity to make reasonable decisions28. As outlined in the Paper, the value of property has significantly increased over the past decade. As such, elderly people who have kept property over the years are commonly unaware of the true value of their property29. At common law it has been noted that to exploit elderly persons, with limited decision making 21 Note: the elder will have a defence to consensual incest where coerced under s222(4), or mentally impaired under s27. 22 Criminal Code 1899 (Qld) s216(3). 23 Criminal Code 1899 (Qld) s349 24 R v Roberts and Roberts [1982] 1 WLR 1 33; [1982] 1 All ER 609; (1982) 74 Cr App R 242. 25 The Office of the Public Advocate and The Queensland Law Society, Elder Abuse: How well does the law in Queensland cope? (2010) at 4.1.1. 26 Criminal Code 1899 (Qld) s408(1)(d). 27 [2008] QCA 130. 28 R v Naidu [2008] QCA 130, per Mcurdo P at 4. 29 The Office of the Public Advocate and The Queensland Law Society, Elder Abuse: How well does the law in Queensland cope? (2010) at 4.1.1. capacity30, by concealing or omitting the true price of a property, namely a residential home, is deemed unconscionable31. Remedies available at Criminal Law in relation to fraudulently acquiring property, combined with the remedies that are available to elderly people in Common Law, protect elder’s or dependent adults against this type of abuse. Neglect Section 285 of the Code provides that it is unlawful for any person having charge of another who is unable, by reason of age, sickness, unsoundness of mind, or any other cause, to withdraw himself or herself from such charge due to their inability to provide themselves with the necessaries of life32. Section 324 of the Code provides that any person who has been charged with the duty of providing for another, the necessaries of life, if found not to have done so without lawful excuse, is liable to 3 years imprisonment33. Section 285 of the Code also holds that any person with such a charge, or duty, is responsible for any consequences in regards to the death, detriment or health of another by reason of omission to perform that duty34. Accordingly, section 290 of the Code provides that it is the duty of any person to not omit any act, which, if not carried out might be dangerous to human life or health. Contravening persons will be accountable for the consequences of such an omission35. Advocacy groups for the prevention of elder abuse have expressed apprehension as to the apparent deficiencies concerning the legislative protections against elder abuse in comparison with the legislation protecting other vulnerable 30 Hall v Grassie (1982), 16 Man. R. (2d) 399 (Q.B.) at 25. Hall v Grassie (1982), 16 Man. R. (2d) 399 (Q.B.). 32 Criminal Code 1899 (Qld) s285. 33 Criminal Code 1899 (Qld) s324. 34 Criminal Code 1899 (Qld) s285. 35 Criminal Code 1899 (Qld) s290. 31 minority groups36. However, the Code, as stated above, provides relevant provisions against neglect, and the failure to provide necessities, applicable to any person under the care of another, including a dependent elder or adult. Psychological abuse Psychological abuse is possibly the hardest form of elder abuse to deal with in a legislative capacity. While it is a form of abuse that is of particular concern, the ability to substantiate claims of purely psychological abuse would be very difficult in a court of law. The impacts of psychological abuse tend to be something that is subjective, and unique to each victim. Creating an effective test to prove this abuse beyond a reasonable doubt would be a very difficult, if not impossible thing to do. The instances where negative psychological impacts are as the result of other forms of elder abuse, relief might be offered when abusers are fully prosecuted for their actions. Purely psychological abuse however, even with policy in place, is something that unfortunately may always evade the protections of legislation. While some cases may be caught under provisions, many more would fall through the cracks, unable to be proven beyond a reasonable doubt. 2. Californian perspective The USA has seen vast development of their laws surrounding elder abuse over the past 40 years. Prior to 1977, no US state had any specific form of elder protection. Today, all 50 states have some type of statute addressing elder abuse prevention, protecting the elderly and dependant adults from neglect, abuse and exploitation to varying degrees37. Many of these laws dramatically limit the portion of elders who can be protected, for example, two in three states 36 The Office of the Public Advocate and The Queensland Law Society, Elder Abuse: How well does the law in Queensland cope? (2010) at 4.4. 37 Arthur Meirson, ‘Prosecuting Elder Abuse: Setting the Gold Standard in the Goldern State’ (2009) 60(2) Hastings Law Journal 437. require elderly people to be completely dependent before special laws will intervene38. California is said to be the leader in elder protection39, being one of 12 states that have legislation to protect all elders and vulnerable adults (regardless of disability) against both physical and financial abuse40. Abuse California’s primary criminal statue addressing elder abuse is §368 of the Penal Code of California41. This section penalises “any person who...wilfully causes or permits any elder or dependant adult...to suffer...unjustifiable physical pain or mental suffering”42. On face value, this provision appears all encompassing – a total protection against elder abuse. However, determining “unjustifiable physical pain or mental suffering” is a subjective test, opening the legislation up to major weakness which is peculiar to abuse against elders43. Having no requirement for actual physical injury would apparently favour an elderly victim, but note, the legislation only favours the victim where the victim is willing and/or able to testify. In the majority of cases, the lack of an objective test means prosecution is not possible, for reasons including, for example, that a doctor cannot testify that certain injuries caused by an abuser would be consistent with pain and 38 Arthur Meirson, ‘Prosecuting Elder Abuse: Setting the Gold Standard in the Goldern State’ (2009) 60(2) Hastings Law Journal 441. 39 Laura Randles, ‘An Act to Increase Penalties for Crimes of Elder Abuse’ (2003) 34(2) George Law Review 398404. 40 Arthur Meirson, ‘Prosecuting Elder Abuse: Setting the Gold Standard in the Goldern State’ (2009) 60(2) Hastings Law Journal 438. 41 Nina Santo, ‘Breaking the Silence: Strategies for Combating Elder Abuse in California’ (2000) 31(3) McGeorge Law Review 813. 42 Penal Code of California §368(b)(1) (West 1999 & Supp. 2009). 43 Arthur Meirson, ‘Prosecuting Elder Abuse: Setting the Gold Standard in the Goldern State’ (2009) 60(2) Hastings Law Journal 442. suffering44. There are a number of circumstances where the lack of an objective test becomes a real issue, including where the elder: Is too stoic, or is ashamed to testify that they felt pain in the attack; Distrusts the justice system; Feels sympathy towards the defendant; Was inflicted with injuries in the attack that cause mental infirmity or inability to testify or give an evidentiary statement against the attacker; Dies as a result of the attack before a statement can be given. In all five situations, expert opinion assessing the extent of the injuries would allow an abuser to be brought to justice. To highlight this issue in practise, a 2009 report by the Rhode Island Department of Elderly Affairs showed that on average, they receive approximately 900 complaints of elder abuse per year; 765 cases are confirmed by case workers; 70 cases get fully investigated; 20 result in criminal charges and even fewer result in conviction45. The legislation also imposes harsher penalties for those who commit crimes of this sort, and for those who are re-offenders46. This was intended to have a preventative effect, especially for deterring re-offenders, however there continues to be a large recidivism rate and little deterrence for re-offenders because the penalties are still so small47. The judge governing an elder abuse case may also impose harsher penalties for enumerated circumstances against a 44 Arthur Meirson, ‘Prosecuting Elder Abuse: Setting the Gold Standard in the Goldern State’ (2009) 60(2) Hastings Law Journal 443. 45 Arthur Meirson, ‘Prosecuting Elder Abuse: Setting the Gold Standard in the Goldern State’ (2009) 60(2) Hastings Law Journal 431. 46 Penal Code of California §667.9 (West 1999 & Supp. 2009). 47 NB: Laura Randles, ‘An Act to Increase Penalties for Crimes of Elder Abuse’ (2003) 34(2) George Law Review 402; the enhanced penalties are from a fine not to exceed one thousand dollars, not more than 6 months in county jail, or both, to a fine not more than two thousand dollars, not more than one year in county jail, or both: Penal Code of California §§368(c) & 19 (West 1999 & Supp. 2009). person 60 years or older48, and there are greater penalties for inflicting great bodily injury on a person over the age of 7049. Neglect In the US, approximately 60% of elder abuse or neglect cases are at the hands of a family member50. No US state requires adult children to care for or monitor their elderly parents51. A duty of care is only owed where taken on voluntarily or through contractual agreement52. For an omission to prevent or aid a suffering elderly person to be punishable, the person must owe the victim a duty of care through some special relationship53. By this principle, an adult child who has witnessed the neglect of their elderly parent is under no obligation to take action to rectify the situation unless they have a legally enforceable duty of care. California is one of 30 states imposing financial responsibility on adult children for indigent parents. However, this legislation is rarely enforced54, and falls short because it doesn’t extend to the physical care and well-being of elderly parents. Mandatory Reporting Laws California has imposed mandatory reporting laws requiring mandated reporters (eg workers within aged care facilities) to disclose known or suspected instances of physical abuse, abandonment, isolation, financial abuse or neglect of an elder 48 Penal Code of California §1203.09 (West 1999 & Supp. 2009). Penal Code of California §§12022.7 & 368(2) (West 1999 & Supp. 2009). 50 Lara Queen Plaisance, ‘Will You Still...When I’m Sixty Four: Adult Children’s Legal Obligations to Aging Parents’ (2008) 21(1) Journal of the American Academy of Matrimonial Lawyers 246. 51 Lara Queen Plaisance, ‘Will You Still...When I’m Sixty Four: Adult Children’s Legal Obligations to Aging Parents’ (2008) 21(1) Journal of the American Academy of Matrimonial Lawyers 246. 52 Lara Queen Plaisance, ‘Will You Still...When I’m Sixty Four: Adult Children’s Legal Obligations to Aging Parents’ (2008) 21(1) Journal of the American Academy of Matrimonial Lawyers 256. 53 Lara Queen Plaisance, ‘Will You Still...When I’m Sixty Four: Adult Children’s Legal Obligations to Aging Parents’ (2008) 21(1) Journal of the American Academy of Matrimonial Lawyers 255; People v Heitzman 886 P.2d 1229 (Cal. 1994). 54 Matthew Pakula, The Legal Responsibilities of Adult Children to Care for Indigent Parents (2005) National Centre for Policy Analysis < http://www.ncpa.org/pub/ba/ba521/ > at 10 March 2011. 49 person or dependant adult55. However various exceptions to the requirements create severe deficiencies in the effectiveness of such provisions. For example, where an elder person complaining of abuse has dementia, the requirement of reporting is based on an assessment by the elder’s care giver – if the care giver thinks it appropriate, then a formal report will/won’t be made. If it is the care giver who is the alleged perpetrator, they will have no one to answer to in respect of such allegations56. Thus, mandatory reporting laws are vastly ineffective57. Tentative Conclusion Californian elder abuse laws don’t seem to be achieving the level of effectiveness as anticipated at their implementation. The problem lies particularly in the lack of reporting of cases, and in legislative vagueness. Provisions for the increase in penalties for perpetrators of elder abuse do not go above and beyond the provisions within the Queensland Criminal Code, or the discretionary application of aggravating factors in sentencing such as the elderly age of victims. 3. Conclusion Protecting our elders is first and foremost a moral duty; legislative regimes are no combat for the issue while people continue to neglect this moral duty. All forms of elder abuse are adequately covered by the Queensland Criminal Code. There appears to be nothing distinguishable in terms of effectiveness that US legislation is achieving ahead of us. Our criminal legislation is not deficient in protection. If cases were reported, and were dealt with under the Code, a proper 55 Nina Santo, ‘Breaking the Silence: Strategies for Combating Elder Abuse in California’ (2000) 31(3) McGeorge Law Review 816; California Welfare and Institutions Code §15630(b)(1) (West Supp. 2000). 56 Nina Santo, ‘Breaking the Silence: Strategies for Combating Elder Abuse in California’ (2000) 31(3) McGeorge Law Review 817. 57 Lara Queen Plaisance, ‘Will You Still...When I’m Sixty Four: Adult Children’s Legal Obligations to Aging Parents’ (2008) 21(1) Journal of the American Academy of Matrimonial Lawyers 246. and appropriate sentence would be imposed. It is the lack of reporting by the general public that needs to be addressed. 4. Recommendations It is recommended that broad mandatory reporting laws be invoked, requiring any persons aware of circumstances of elder abuse or neglect to report it to the relevant Queensland authority. It is recommended that wide community education about elder abuse be initiated, not only to increase awareness, but also to encourage people, particularly victims, to report elder abuse. It is recommended that there be an increase in places of refuge for victims who are dependant, to encourage them to report their cases.