Guidelines for Public Private Partnerships - Treasury

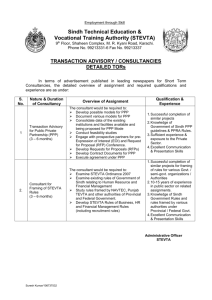

advertisement