B'Tselem - Activity of the Undercover Units in the Occupied

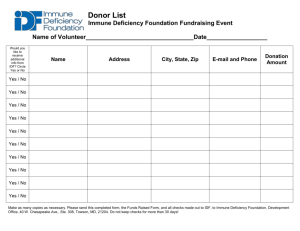

advertisement