Ritvik Factum - JurisDiction

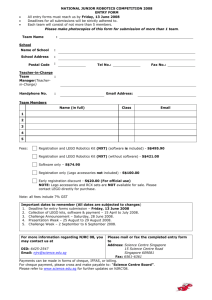

advertisement