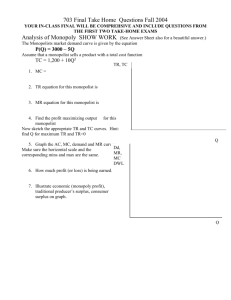

Monopoly - Eastbourne College Portal

advertisement

Monopoly Some definitions The market structure of perfect competition was at the most competitive end of the spectrum, with numerous firms all competing wildly. Now we jump to the other extreme. In the market structure of monopoly, there is only one firm in the whole market. In fact, that single supplier constitutes the entire industry. As with perfect competition, we need to look at the assumptions that need to be made, but in this case there are not so many. Effectively, the monopolist can more or less do what it wants! The Assumptions 1. . As we have said, there is only one firm, but the number of buyers can be numerous. 2. . The complete opposite of perfect competition. With monopoly, there are lots of barriers to entry and exit. It is because of these barriers, usually imposed by the monopolist, which stop other firms trying to compete. Details of these barriers are outlined below, although we did cover barriers in unit one of the AS level. 3. . Not such an issue with monopoly. In a sense, the monopolist knows everything that is going on in the industry because it is the industry! 4. . One firm means one product, so I suppose it is homogenous as in perfect competition. 5. . Again, we assume that the monopolist aims to maximise its profit. 6. . There is only one firm, so factors don’t need to be mobile between firms; they always stay with the one firm! Factors might be mobile between industries, but we are not concerned with that at the moment. 7. . Firms in perfectly competitive markets are price takers. This means that they have absolutely no control over the price they charge. Monopolists are price makers. It is the only firm in the industry, so they make the price; they decide what the price is going to be. 1 Barriers to entry and exit Probably the most important characteristic of a market is the extent to which the firms in that market can erect barriers to entry to stop new competitors from entering the industry and barriers to exit to stop existing competitors from leaving the industry. The level of competition faced by a firm is probably the main determinant of its behaviour. Although this section is called ‘Barriers to entry and exit’, many of the barriers to exit are, by their very nature, barriers to entry as well. For example, it is difficult to leave an industry, even when making short run losses, if a lot of capital is tied up in the business. The knowledge of this fact before one considers setting up a business may be enough to put one off starting in the first place! The barrier to exit has become a barrier to entry. With this in mind, the next section is called ‘Barriers’ rather than ‘Barriers to entry’, or ‘Barriers to exit’. The barriers 1) As mentioned above, this can act as a barrier to exit as well as a barrier to entry. Quite simply, if you are struggling to get the funds together to start the business, then this is a ‘barrier’ to you entering the market. Even if you do have the capital, the worry that you will be stuck in an unprofitable situation with a lot of unrecoverable capital invested in the business may stop you entering the market in the first place. These ‘unrecoverable’ costs are often referred to as sunk costs. In most markets, if things go pear-shaped you can sell much of the equipment on to other firms in the industry. But costs like advertising are unrecoverable. Obviously, the larger the industry you intend to enter, the bigger the capital (and sunk) costs and the bigger the barrier to entry (and exit). 2) Existing firms may be operating a predatory pricing policy. As the title suggests, this is a policy designed to kill off competitors by reducing the price below cost price temporarily. The idea is that once the competitor is killed off, the firm can raise the price back up to the old level and steal all their customers. Limit pricing is similar to predatory pricing, except the firm in question is trying to ‘limit’ the entry of new firms by setting the price low enough to prevent new firms entering, but high enough to still make some sort of profit. Actions like this by incumbent firms obviously act as a barrier to entry for potential new firms. 3) If existing firms are large, they are probably benefiting from economies of scale. This means that their average costs are lower by virtue of their size. Bulk buying economies is a good example. Potential firms are likely to start on a smaller scale and so will find themselves at an immediate cost disadvantage. 2 4) A patent is something that a firm may apply for if it has just invented a genuinely original product. If the patent is granted by the government, it gives the firm legal protection to produce the product without competition for a given time period (usually a number of years). After all, what is the point of spending time and money inventing something if everyone can copy you straight away? Patents create incentives for individuals to be innovative. Obviously this creates a barrier for firms wishing to join this new market. There are other legal barriers imposed by the government. The Post Office, for example, is the only body that is allowed to offer postal services costing less than £1. Notice that there are loads of firms offering delivery services for larger packages (like DHL and FedEx), but nobody else offers 46p stamps for small letters. 5) Established large firms tend to spend a fortune on advertising. Apart from the fact that they are trying to get you to buy the product in the short term, the long term aim is to create brand loyalty. How many of you, when buying Coca-Cola from a newsagent, ask for a ‘Coke’ even if the only brand they sell is Pepsi? Does your mum do the vacuum cleaning or the hoovering? In both cases, the brand name is so entrenched that most people use the brand name as the generic name for the product. In the case of ‘Hoover’, the brand name has even turned into a verb! Having a strong brand image is very powerful for the firm in question and creates a huge barrier to entry for a potential new firm. 6) Vertical integration is a form of merger. It is where one firm merges (or takes over) another in the same industry but at a different level of production. For example, a firm that manufactures cars could merge with a firm that produces car parts, or with a steel plant. This is known as Backward vertical integration. If the car manufacturing firm merged with a group of car showrooms, this would be Forward vertical integration. In the first case, the firm would now have control over some of the raw materials. In the second, it would have control over some of the retail outlets for cars. In both cases, the firm has become more powerful, making it harder for new firms to compete. The knowledge of this extra power would put off new firms from entering the car industry. 7) Although it is difficult to put figures on this, established firms are likely to have a cost advantage over new firms because they have more experience of the industry in question. An established restaurant will know when it will be busy and when it will be quiet. They are less likely to order too many materials or employ too many waiters on a given night. These are the sorts of things that can only be learnt with experience. 3 Are there any examples of monopoly in the real world? Pure monopolies are almost as rare as perfectly competitive markets. The Post Office has a pure monopoly in the market for sending letters. Otherwise, there are many monopolistic markets, put no pure monopolies. The recently privatised utilities used to be monopolies. British Telecom used to be the only company that supplied land-line telephone services. It still has some monopolistic power (approx 60% market share), but the industry is now much more competitive, especially with the growth of mobile phones. Water, gas and electricity all used to be pure, state run, monopolies as well. There is now a lot of competition in the markets for gas and electricity, but although the Water industry has been split up, some would say that the resulting firms are now regional monopolies. This means that they have monopoly power over the area they serve, but not, any longer, over the whole of the UK. Natural monopolies Before we move on to the diagrams, you need a definition for a natural monopoly. This is where the market structure of monopoly is the ‘natural’ state of affairs in an industry. This tends to happen in industries where the sunk costs are absolutely huge. The utilities are considered to be natural monopolies, despite the advent of competition. Consider trying to compete with the electricity board in the old days. You would have to find the money to build a national grid! If things did not work out, there wouldn’t be many firms willing to buy the grid from you! Of course, even today with competition in the market for electricity, the government couldn’t get around this problem. There is still only one national grid. The companies compete to supply customers with the same electricity using the same distribution system. Equilibrium output A monopolist is the only firm in the industry, so its average cost curve is the standard U-shaped curve and the marginal cost curve cuts the average cost curve at its lowest point, as you would expect. The average revenue curve (the demand curve) will be downward sloping, assuming the good in question is normal, and the corresponding marginal revenue curve will be below the average revenue, downward sloping and falling twice as fast. (See the handout on ‘Costs and revenues’ for details). 4 The diagram above shows the equilibrium output for the monopolist. Notice that I haven’t distinguished between the short run and the long run. There is no need. A monopolist can make profit in the short and long run, as long as it can maintain the barriers to entry. It can also makes losses (see the next diagram), although the firm might pull out rather than keep making losses into the long run. If the industry’s demand curve is downward sloping (which is usual) then so will the monopolist’s. Remember that the monopolist is the industry. If the firm wants to increase sales, it must lower the price. If they want to increase the price they must accept lower sales. In other words, they cannot set both price and quantity. To find the equilibrium price and quantity, we must, again, apply the maximising condition, MC = MR. This occurs at point A. To find the quantity demand/supplied, we simply drop a line vertically, giving Q1. To find the price, we must draw a line vertically upwards until it hits the average revenue curve and then draw a line horizontally to the y-axis, giving P1. Remember that the AR curve is the price curve, so it is from this curve that we read the price. In the diagram above the monopolist is earning super normal profit. This is because at output Q1, AR > AC. Profit per unit at Q1 is the distance BC, and total profit is represented by the red box, BCDP1. The diagram above shows how a monopolist might make a loss. It is the same diagram except the average cost curve is very high and, more importantly, above the average revenue curve. In this situation, the firm is bound to make a loss, but it will still minimise its losses by producing at the level of output where MC = MR. This occurs at point E, giving a price of P2 (read off the AR curve) and quantity Q2. The loss per unit is FG and the total loss is represented by the box, FGHP2. 5 The costs and benefits of monopoly When we did ‘Market failure’ for AS level, the fact that monopoly is a form of market failure was discussed. If a market is monopolistic in structure, then the price will tend to be higher and the quantity supplied lower than the totally efficient structure of perfect competition. If this market were a monopoly, profits would be maximised where MC = MR (at point E) giving the equilibrium price Pm and quantity Qm. Imagine that this market was perfectly competitive. The equilibrium would now be where the market demand curve (AR) crosses the market supply curve (MC). This occurs at point C, giving the equilibrium price Ppc and quantity Qpc. As expected, the price is higher and the quantity lower if the market is a monopoly. What is the effect on society? We need to analyse this in terms of consumer surplus and producer surplus (or profit). If this market were perfectly competitive, consumer surplus would be the triangle . There is no producer surplus (because AR = AC), so the consumer surplus represents the total benefit to society. If this market were a monopoly, consumer surplus would be reduced to the triangle , due to the higher price, but there would be some producer surplus, equal to the rectangle . So, total benefit to society under monopolistic conditions is represented by the trapezium . Hence, as a result of this market moving from perfect competition to monopoly, there is a deadweight loss to society, represented by the triangle . This is effectively the loss to consumers as a result of being denied the chance to purchase output QmQpc at prices between Ppc and Pm. Also, some would argue that the producer surplus, which was once consumer surplus, was better off in the hands of the consumers, rather than a few ‘fat cat’ monopolist managers. I suppose it could also be argued that the profit ends up in the hands of shareholders (who are the consumers in a share-owning democracy) via dividends. Some of the profit may be re-invested into the company, which might lead to future improvements in efficiency and lower costs. 6 So, monopoly is bad. Or is it? The following diagram shows a situation where market structure of monopoly might be better for society than perfect competition. In the diagram above, monopoly is seen to be hugely beneficial to society. And why is this? Our initial analysis overlooked the fact that large firms usually benefit significantly from economies of scale. This shifts the MC curve downwards. If this shift is very large, as is assumed in the diagram above, then a monopolist may charge a lower price and produce a higher output than if the market were perfectly competitive. The monopolist maximises its profits. MC = MR occurs at point E, giving price Pmx and quantity Qmx. This means that price is now lower and output is higher than under conditions of perfect competition. In reality, society is likely to gain to some extent from the monopolist’s economies of scale, but it will also lose out, as the monopolist will probably still set a higher price than if the market were perfectly competitive. One last point to note. The benefit to society is, in fact, just a benefit to the monopolist, whereas the loss to society is a loss to the consumers. Which group in society is more important? [It should be noted, though, that the profit might return to shareholding consumers via dividends. It could also be used to benefit the consumer through productivity improving investment in the company] Moving away from the diagrams, there is another issue: innovation. Some argue that a monopolist can afford to spend huge amounts (often fruitlessly) on research and development. They are more likely, therefore, to create new, and better, products. Others would argue that due to the lack of competition that the monopolist faces, it relaxes, seeing no need to be innovative, whereas firms in a more competitive environment have the incentive to innovate to get ahead of the pack. 7 Price discrimination Racial discrimination is defined as a situation where a certain race is discriminated against for no other reason than the fact that they are a different race. Price discrimination is a situation where certain consumers are discriminated against. Whereas in perfect competition, all firms charge exactly the same price, a monopolist (or a firm with monopolistic power) can charge different prices to different consumers even though the cost to the firm is exactly the same. Examples fall into three categories : 1) (e.g. different phone charges and rail tickets prices at peak and off-peak times). 2) (e.g. car prices are higher, in general, in the UK compared with the rest of the European Union). 3) (e.g. the lower prices paid by the young, old, unemployed and students at cinemas and hairdressers). In a slightly more subtle way, price discrimination is also happening if a good has the same price for everybody, even if the costs vary between consumers (e.g. the price of a first class stamp is the same for everybody however far the letter has to travel in the UK). Note that price discrimination should not be confused with price differentiation. This is where prices do differ, but they reflect different costs of production. As we shall see shortly, air travel is an example of price discrimination. First class passengers pay a much higher price. Obviously the cost of this service is also much higher, but given that the price can be up to 10 times higher, do you think that the costs are 10 times higher? The conditions required for effective price discrimination 1. The firm in question must have some . This does not mean that the firm must be a monopolist, but an element of monopolistic power would be useful. 2. The firm must be able to . Phone companies can do this easily. If you make a call after 6pm then it is off-peak. At 5.55pm you are charged at a higher rate. It is easy for them to keep ‘peak’ and offpeak’ separate. Other markets are more difficult to separate. Everyone knows that Levi’s 501 jeans are cheaper in America than in the UK. The markets are separate, though, because most people will not spend £400 on a return flight to New York to save £20 on a pair of jeans. 8 3. The buyers in the different, separated, sub-markets must have very different . Also, they should be identifiable by the firm at a reasonable cost. You will see why this is so important in the diagrams below. 4. The firm must be able to . The diagrams The following set of diagrams helps to explain why it can be profitable for a firm to price discriminate. It is quite difficult to draw these diagrams accurately so you should practise, especially as this is quite a popular essay question with examiners. The secret is to draw the ‘total market’ diagram first on the right, and then draw long horizontal lines right across the page to signify the industry’s average cost and marginal cost before you start the other two diagrams. These lines should then act as a guide to make sure that the inelastic sub-market has a big profit box and the elastic sub-market has a much smaller profit box. Taking the example of airline flights, the elastic sub-market is economy class and the inelastic sub-market is business class. With economy class, output is high (30 customers), but at a relatively low price (P2). With business class, output is low (10 customers), but the price is very high (P3). Businessmen’s demand for air travel is very price inelastic. Apart from the fact that the company pays, so they don’t care how high the price is, they need the extra comfort because they may have an important meeting for which they cannot be tired. Those of us looking for a flight for a holiday have a much more price elastic demand. Price is all important. It is a relatively big purchase for most households, so most people will be very price sensitive and shop around. Quality of service is not such a big factor in the choice of airline. If the airline offered one service at price P1, there would be no shortage of business customers, but most of them will use the better service at price P 3 anyway. There would, though be a significant decline in the number of ‘normal’ passengers using the airline. By splitting the markets the firm should make more profit overall. 9