- Elwood Herring

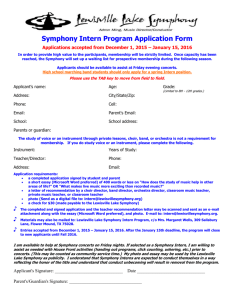

advertisement