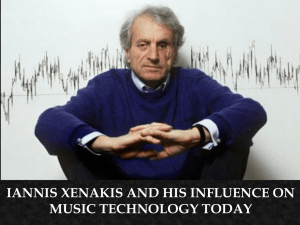

Xänorphica

advertisement