Exporting jobs or watching them disappear

advertisement

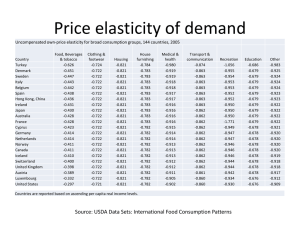

Exporting jobs or watching them disappear ? Relocation, employment and accumulation in the world economy Jayati Ghosh Centre for Economic Studies and Planning School of Social Sciences Jawaharlal Nehru University New Delhi 110 067 [email : jayati@ndf.vsnl.net.in] Draft paper for discussion at IDPAD Conference on “Globalisation, structural change and income distribution” Chennai, 14-17 December 2000 1 I The issue of the international relocation of manufacturing production is one which has received and continues to attract a great deal of attention from not just economists but policy makers, trade unions and other analysts across the world. There is a widespread perception that the past decade in particular has seen a significant shift in the structure of international manufacturing production, such that developing countries now account for nearly a quarter of world manufacturing goods exports, up from just over one-tenth two decades ago. Such relocation, which in turn is generally supposed to imply a net loss of manufacturing jobs in the North and a net expansion of such jobs in the South, has been seen as being driven by both by the movement of capital, as multinational companies in particular move to areas characterised by cheaper labour, and by trade liberalisation which has allowed manufactured goods produced in Southern locations to penetrate Northern markets. It is recognised that both of these processes have been greatly facilitated by technological change which has allowed for the locational breakup of the productive process and the separation of various elements of it with differing types of skill requirement. This has enabled what Feenstra [1998] describes as “the disintegration of production”, with the associated geographical separation of different parts of the production process and increase in intra-industry trade. This is obviously a matter of great economic and political relevance, and it has defined much of the reaction by workers in the North, who see their employment opportunities challenged by this “great sucking sound” of jobs moving South, through investment and trade. Conversely, workers and other groups in the South have been encouraged to view protectionist pressure in the North as part of an attempt to prevent them from reaching the living standards of the North through export-oriented employment. Quite often, such concerns at either end , reflected in and emerging from the politics of the situations, have also been mirrored in the work of economists. 2 Table 1 : Share of developing countries in world manufacturing goods exports Year Per cent 1980 11.2 1990 17.2 1991 18.5 1992 19.2 1993 21.4 1994 22.3 1995 22.9 1996 23.2 1997 24.1 1998 23.7 1999 24.8 Source : World Trade Organisation Relatively early work in searching for empirical substantiation of this perception of the export of manufacturing jobs from North to South was found in both conservative mainstream and progressive economics traditions, through the writings of Beenstock [1985] and others at one end of the spectrum, and Froebel, Heinrichs and Kreye [1980] at the other. The book by Adrian Wood [1994] was followed by a substantial debate on the extent and implications of such relocation for employment in both the North and the South. Wood’s argument, which was in essence just an extension of the Heckscher-OhlinStolper-Samuelson results, was that the lowering of trade barriers and the liberalisation of external trade would cause trade, and therefore production patterns, to move along the lines determined by factor-endowment-based comparative advantage, especially when labour is gradated into different factors according to degree of skill. Wood argued that expansion of trade effectively linked the labour markets of North and South more closely. This did not necessarily bring about convergence in wages. But it did, according to him, accelerate development in the South through substantial employment increases. In the North, however, even though such trade has raised average living standards, it has hurt unskilled workers and thrown them out of jobs. Much of the discussion that followed [see Journal of Economics Perspectives, 1995 and 1998, for example, as well as Freeman and Katz, 1995 and Leamer 2000] has focused on the effects of this process on Northern workers, and the debate has been about the extent of the damage that is likely to ensue as well as the best way of dealing with it (as in the strategies of 3 protectionism versus training to improve skills of unskilled and less skilled workers). There has also been debate on not just the extent but also the causes of job loss, and whether trade or technological change has played a greater role. It has been argued by one strand of the literature [e.g. Leamer, 2000] that technology must play the determining role in changing labour requirements in overall production, since the total manufactured exports of all developing countries are still quite small in relation to developed countries’ GDP. While some have suggested that the two processes of technology and trade openness are “observationally equivalent” and effectively work in tandem, Wood has argued that labour-saving technological change in the North has itself been induced as a response to trade competition from production using cheap labour in the South. Interestingly, the effects of such global integration on workers in developing countries have generally been taken to be unambiguously positive, in terms of increasing employment opportunities especially for less skilled workers. This has been true even of economists from developing countries who have otherwise questioned the supposition that there would be necessarily be large negative effects on unskilled workers in the North. Of course, this is implicit in the very idea of “exporting” jobs : if they are being exported from the North, presumably they are being “imported” somewhere else, that is into the South. Thus, if the North is a net loser of less skilled jobs in manufacturing, then the presumption is that the South is a net gainer of such jobs. At one level, this is fairly easy to understand : clearly, if there are production shifts in manufacturing and associated job losses in one part of the world, it is likely that such jobs have moved elsewhere particularly if the manufacturing production is increasingly located (at the margin) in that part of the world. But while this may follow easily from the analytics, it sits uneasily with the actual experience of the vast majority of developing countries, who have experienced very substantial losses in manufacturing employment through the process of greater openness and integration of capital markets through finance and goods markets through trade. For them, the question would more likely be, not how many manufacturing jobs have moved to them or how much net expansion in manufacturing employment there is, but rather : where have all the jobs gone ? Also, just as the trading pattern is supposed to have increased the skill premium on labour in the North, it should have reduced it in the South, or at least made unskilled/less skilled work more easy to find than before. This too does not seem to conform to the experience of most developing countries. 4 In this paper, these issues are sought to be addressed through an examination of patterns of manufacturing employment expansion in some of what are seen as the more prominent and “dynamic” developing economics of the recent past. In the next section, the major tendencies in terms of manufacturing employment by sector are considered, with a view to considering the extent to which there has actually been a net export of such jobs to developing countries. In particular, expectations with regard to the employment elasticity of manufacturing are examined in the light of the available evidence. In the final section, there is an attempt to explain the observed patterns in terms of a broader understanding of the dynamics of contemporary capitalism. II It is generally acknowledged that the increase in manufacturing production, and manufacturing exports in particular, is confined to a small handful of developing countries. Typically these countries have also been beneficiaries of substantial foreign capital inflows in various forms, although it remains a subject of debate whether this has been a cause or effect of high rates of export growth. At any rate, it is these countries - mostly in East Asia with a few in Latin America - which have been dominant in contributing both to the increase in the share of developing countries in total world exports of manufacturing goods, and in the higher rates of economic growth that have been found in these developing country regions as compared to the rest of the world. Indeed, Ghose [2000] suggests that as few as 13 countries 1 explain almost all the significant increase in developing country manufacturing exports over the past two decades. Thus, the share of these countries in total merchandise exports from developing countries increased from 33 per cent in 1980 to 72 per cent in 1996, while their share of manufactured exports of developing countries went up from 73 per cent to 88 per cent over the same period. They also commanded an increasing (and dominant) share of foreign direct investment into developing countries, which almost doubled after 1970 to reach 82 per cent in 1995. Obviously, if the manufacturing jobs have been moving anywhere, then it must have been to these locations, since they account for the lion’s share of manufacturing exports of all developing countries. The stagnation or even 1 1These countries are Argentina, Brazil, China, Hong Kong China, India, Indonesia, Malaysia, Mexico, the Philippines, Singapore, South Korea, Taiwan China and Thailand. 5 deindustrialisation that has been noted elsewhere would then appear to be a reflection of the fact that the more traditional division of labour has not changed for most of the other countries, in which export of primary commodities serves to finance (albeit only partially) the import of manufactured goods from more developed countries. Table 2 : Growth of manufacturing employment, 1985-98 (UNIDO data) compound 1985 1998 rate of (000s) (000s) growth per annum China 29743 61582 5.8 South Korea 2395 2615 0.7 Malaysia 473 1448 9 Philippines 618 968 3.5 Taiwan 2462 2373 -0.3 India 6469 9300 2.8 Argentina 1174.4 887.5 -2.1 Brazil 4187 3115 -2.2 Chile 185 325 4.4 Mexico 994 920 -0.5 Source : Calculated from UNIDO Country Industrial Statistics Tables 2 and 3 provide some information on manufacturing employment in some of the more significant developing countries, from two different sources : UNIDO and ILO. It is clear that a few countries - notably People’s Republic of China, Malaysia and Chile - did experience substantial increases in manufacturing employment over the period from the early 1980s. However, many of even the supposedly most dynamic developing countries experienced only low to moderate employment growth in manufacturing, and for several especially Brazil - such employment declined in absolute numbers over the period. In fact, compared to the expectations caused by the very significant shift in terms of international manufacturing production that was evident from Table 1, the increase in manufacturing employment, limited as it was to a few countries, seems quite unimpressive. Table 3: Growth rates of paid employment in manufacturing (ILO Data) 6 Country PR China Malaysia Indonesia Thailand Philippines South Korea India Sri Lanka Brazil Colombia Mexico Kenya South Africa Zimbabwe Period 1985-94 1981-94 1980-89 1981-93 1981-93 1980-90 1980-90 1980-97 1985-98 1980-97 1985-98 1980-97 1980-93 1980-97 Annual rate of growth 4.8 7.3 9.8 7.3 0.9 4.4 1.4 2.8 -6.8 0.4 2.9 2.5 -.1 1.3 Source : Calculated from ILO Yearbooks of Labour Statistics Table 4, which shows evidence of employment growth in aggregate industry rather than just manufacturing, once again suggests a similar picture of rapid employment generation in only a tiny handful of countries. It is true that Indonesia, Malaysia and Thailand exhibit very rapid rates of employment expansion in manufacturing production, and a near 5 per cent rate of annual increase in such employment in a manufacturing sector as large as that of China must imply a fairly large number of jobs in the aggregate. But this increase in only four countries occurs even as many of the supposedly most dynamic exporters (such as South Korea and Taiwan China) show very low rates of employment growth while in other countries it is moderate at best. In several large semi-industrial economies such as Argentina, Brazil and South Africa, industrial employment growth was actually negative in the 1990s. It is also interesting that in some of the most prominent high exporting countries of the recent past, such as PR China, the rate of employment expansion has decelerated in the 1990s when manufacturing export growth supposedly peaked. Note that these data refer to the “pre-crisis” period, so that the financial crisis and subsequent recession cannot be held responsible for this. 7 Table 4 : Employment growth in industry Annual rate of growth (%) 1980-90 1990-96 Argentina 0.9 -6.7 Brazil 2.3 -0.5 Chile 3.8 3.8 Colombia 2.1 3.3 Mexico 3.7 3.3 PR China Indonesia Malaysia Philippines South Korea Taiwan Thailand 6.9 4.4 4.8 2.5 4.9 4.2 6.4 2.8 6.8 6.6 5.1 0.9 0.1 7.6 India Sri Lanka -0.7 3.4 1.5 3.4 Kenya 2.9 1.4 South Africa 1.9 -19.6 Zimbabwe 2 6.5 Source : ILO Key Indicators of Labour Market The point is, of course, that such data refer to total manufacturing or industrial employment, rather than simply the export oriented manufacturing job creation alone. They therefore reflect the fact that just as there are some jobs being created by export expansion, there are other jobs being lost because of import penetration consequent upon trade liberalisation. This is an issue that we will return to subsequently : suffice it to say at this point that for the developing country concerned, obviously the concern is with net job creation or destruction. And here, even for the small and highly favoured group of successful manufactured goods exporters, the scale of employment expansion in manufacturing does not in general appear commensurate with the increasing shares in world trade. For the vast majority of developing countries which are not covered in this paper, most studies have shown [UNCTAD 1999 summarises several of these] that manufacturing employment has actually stagnated or shrunk over the past decade. 8 Most of the studies which take a factor-content approach to the effects of trade (or indeed, to the analogous and associated effects of relocative FDI) have emphasised that the process of job shift occurs through changing patterns of production in both North and South, such that within particular manufacturing sectors the more unskilled labour-intensive branches and activities are taken up in developing countries and the more skilled-labour intensive activities are absorbed by Northern production. [Wood, 1998; Krugman, 2000] As a result, the expectation is that with greater openness and more trade, the employment intensity of manufacturing production should rise in the South (or at least in those economies where export-oriented manufacturing production is significant) while it should fall in the North. [Indeed, Ghose, 2000, using the UNIDO data set for the period 1980-96, arrives at just such a result. He also finds that within Asian developing countries, export-oriented industries show higher employment elasticities of manufacturing production than importcompeting industries.) However, such an outcome is not obvious, since it would depend upon all or most trade being determined along Heckscher-Ohlin lines, with all the restrictive assumptions (constant returns to scale, perfect competition, balanced trade, and so on) associated with those results. An examination of the data from both ILO and UNIDO once again suggests that changes in the employment elasticity of manufacturing production have varied significantly across the relevant countries, and do not necessarily conform to the expected pattern. At this point it is necessary to record some important caveats with respect to the data sets used. As most researchers in the area will know, the cross-country data sets provided by a range of international organisations are problematic and often highly suspect, and the basis for comparability is no always clear. In the case of the employment data, and particularly when it comes to working out employment elasticities of production or value added, the matter is further complicated by several gaps in the time series and extrapolations that have been inserted by the relevant organisation. The ILO sources tend to be more consistent with respect to employment, but the value added data implicit in their calculations may be more suspect. The UNIDO source not only manages to produce employment data for several countries which are not to be found in the national statistics (on the basis apparently of reporting by member governments and extrapolation) but also somehow gets around the problem of huge gaps in the time series for a very large number of countries. Nevertheless, these are the data sets used here, not only because they are really all we have for purposes of identifying larger trends and making international comparisons, 9 but because they are the sources that have generally been used in the literature. Table 5 presents calculations of the employment intensity of aggregate manufacturing value added, based on ILO data, for selected developing and developed countries. It is evident that the employment elasticities emerging from this data set are all close to zero, and there is really little to choose across such countries, nor is there any clear-cut evidence of increases in such intensity in developing countries and declines in developed countries. Table 5 : Employment elasticity of manufacturing production (based on ILO data) 1980-90 1990-95 Indonesia -0.005 0.001 South Korea 0.003 -0.0001 Taiwan -0.003 0.004 India -0.59 0.004 France 0.003 -0.02 Japan 0.003 -0.005 United Kingdom 0.007 -0.03 United States -0.01 0.04 Source : Calculated from ILO Key Indicators of Labour Markets A different source - the UNIDO data set - is brave enough to provide information which can be used to calculate employment elasticities for a number of countries over the period 1985-98, in other words the peak globalisation phase. These employment elasticities have been calculated for some of the countries which are routinely described as among the more successful of the new manufacturing goods exporters, and are typically seen as the most important destinations for the jobs which are supposedly being relocated to the South. Unfortunately, such data are not available for the largest and most prominent of such economies - that of the People’s Republic of China. However, they are to be found for many of the other major manufactured goods exporters among developing countries, and the relevant calculations by country and sector are presented in Table 6. What is striking - at least to this researcher - is how low most of the employment elasticities appear to be. Even more striking is the large number of negative elasticities that emerge, 10 especially - but not exclusively - in South America, and also for a range of manufacturing sectors that are typically thought of a being “labour-intensive”. It is also worth noting that the elasticities range very widely across developing countries with otherwise similar characteristics. Table 6 : Employment elasticity of manufacturing production By manufacturing sector and country, 1985-1998 (based on UNIDO data) Source : Calculated from UNIDO Country Industrial Statistics, 2000 South Korea Employment elasticity Food products Beverages Textiles Clothing Leather products Footwear Industrial chemicals Other chemicals Plastic products Glass & products Metal products Non-electrical machinery Electrical machinery Transport equipment Prof & scientific equipment 0.05 -0.78 2.07 1.09 0.44 -0.49 0.35 0.09 0.74 0.15 0.67 0.99 0.05 0.52 -0.17 Malaysia Annual growth rate of value added 5.1 5.1 -2.22 -4.19 -9.41 -9.41 13.13 13.13 5.79 7.15 4.33 8.25 10.67 10.36 4.85 Employment Annual growth elasticity rate of value added 0.65 5.95 -0.09 6.17 0.44 12.55 1.36 3.82 -2.02 -8.75 -9.29 -1.14 0.97 9.79 2.49 4.63 Food products Beverages Textiles Clothing Leather products Footwear Wood products Paper products 11 Industrial chemicals Other chemicals Rubber products Plastic products Glass & products Metal products Non-electrical machinery Electrical machinery Transport equipment Prof & scientific equipment 12 0.83 0.65 0.45 1.24 0.97 0.69 0.82 0.76 0.78 3.22 9.54 10.8 16.85 13.39 11.95 18.39 17.81 21.13 16.09 4.24 Philippines Food products Beverages Textiles Clothing Leather products Footwear Wood products Paper products Industrial chemicals Other chemicals Rubber products Plastic products Glass & products Metal products Non-electrical machinery Electrical machinery Transport equipment Prof & scientific equipment Taiwan Employment Annual growth elasticity rate of value added 0.25 9.22 -0.06 12.56 -0.54 3.32 0.47 9.22 0.89 10.76 0.78 9.22 -1.13 5.68 0.56 8.56 0.23 12.91 0.21 12.91 0.08 13.47 2.25 3.46 0.05 13.96 0.62 11.31 0.31 20.41 0.54 21.64 0.2 40.57 0.43 13.89 Employment Annual growth elasticity rate of value added -0.59 2.21 0.57 6.77 -38.5 0.12 0.75 -8.47 0.34 -7.47 1.2 -13.74 0.71 4.37 0.16 8.92 0.09 8.06 0.26 1.95 -0.92 -.51 8.82 4.56 -0.12 4.73 Food products Beverages Textiles Clothing Leather products Footwear Wood products Paper products Industrial chemicals Other chemicals Rubber products Plastic products Glass & products 13 Metal products Non-electrical machinery Electrical machinery Transport equipment Prof & scientific equipment 0.42 0.54 0.14 0.18 -0.75 Thailand 6.82 10.43 5.63 2.06 -2.85 Employment Annual growth elasticity rate of value added 11.73 0.83 -0.6 15.32 8.03 0.62 54.13 0.62 0.43 17.29 0.29 17.33 0.43 11.8 0.83 7.24 0.51 12.71 1.82 12.71 -0.18 12.91 0.5 28.71 1.42 25.79 1.49 13.93 0.44 25.21 Food products Beverages Textiles Clothing Wood products Paper & products Industrial chemicals Other chemicals Rubber products Plastic products Glass & products Metal products Non-electrical machinery Electrical machinery Transport equipment Indonesia Employment Annual growth elasticity rate of value added 0.41 15.25 0.54 15.41 0.91 9.04 0.9 20.96 1.03 19.65 4.28 10.38 1.98 4.47 1.02 14.93 1.15 8.79 0.47 8.59 Food products Beverages Textiles Clothing Leather products Footwear Wood products Paper products Industrial chemicals Other chemicals 14 Rubber products Plastic products Glass & products Metal products Non-electrical machinery Electrical machinery Transport equipment Prof & scientific equipment India Food products Beverages Textiles Clothing Leather products Footwear Wood products Paper products Industrial chemicals Other chemicals Plastic products Glass & products Metal products Non-electrical machinery Electrical machinery Transport equipment Prof & scientific equipment Argentina 0.36 1.43 0.85 1.83 -1.05 1.55 1.51 -11.39 8.74 8.74 10.25 5.4 -10.99 10.27 4.96 -1.81 Employment Annual growth elasticity rate of value added -1.41 4.98 -4.93 4.98 -0.18 6.25 0.81 -2.8 0.95 -0.19 0.68 -2.8 -0.57 1.81 -1.1 7.06 -1.43 7.06 -0.98 7.55 -3.54 7.55 -0.18 8.99 1.78 1.77 -0.64 6.68 -0.31 10.41 -5.87 7.42 -2.05 5.97 Employment Annual growth elasticity rate of value added -0.66 4.03 -0.38 2.64 13 -0.54 -0.36 2.5 -1.3 1.87 -3.3 1.71 Food products Beverages Textiles Clothing Leather products Footwear 15 Wood products Paper products Industrial chemicals Other chemicals Rubber products Plastic products Glass & products Metal products Non-electrical machinery Electrical machinery Transport equipment Prof & scientific equipment Brazil -4.34 -0.65 -0.75 -0.8 -0.72 0.44 -1.56 -5.56 0.15 7.57 -2.3 0.06 1.51 4.11 4.71 2.23 8.47 6.25 1.67 1.24 -3.59 -0.35 2.07 -7.1 Employment Annual growth elasticity rate of value added -1.46 2.31 1.81 -2.55 4.31 2.46 -1.39 1.89 -3.32 1.14 -4.36 0.75 8.26 -1.02 -2.6 2.09 -1.27 1.86 Beverages Textiles Wood products Paper products Rubber products Plastic products Non-electrical machinery Electrical machinery Transport equipment Chile Employment Annual growth elasticity rate of value added 1.25 4.0 0.78 5.91 0.84 -0.94 -0.78 -2.93 3.75 0.71 -6.11 -0.35 -0.95 -4.05 1.07 5.59 Food products Beverages Textiles Clothing Leather products Footwear Wood products Paper products 16 Industrial chemicals Other chemicals Rubber products Plastic products Glass & products Metal products Non-electrical machinery Electrical machinery Transport equipment Prof & scientific equipment Mexico Food products Beverages Textiles Clothing Footwear Wood products Paper products Industrial chemicals Other chemicals Rubber products Plastic products Glass & products Metal products Non-electrical machinery Electrical machinery Transport equipment Prof & scientific equipment 1.29 0.65 1.14 2.32 0.5 0.76 0.26 0.37 3.86 1.1 5.48 8.07 3.74 4.06 12.43 7.41 13.86 7.11 2.55 7.55 Employment Annual growth elasticity rate of value added -0.2 3.21 0.32 3.21 -3.4 1.81 -1.31 1.81 -5.18 1.81 -13.7 0.36 -0.86 2.86 -1.09 2.84 0.44 2.84 -1.03 2.84 0.41 2.84 -0.5 2.98 -0.25 6.03 -0.11 6.03 -0.51 -0.08 -0.08 6.03 -0.39 6.03 Some of these figures may also be slightly misleading. Thus, it turns out that for South Korea, the only elasticities which are greater than unity are in the textiles and clothing sectors, which are declining industries, and here the result comes about because both value added growth and employment growth have been negative over this period. The sectors which show the highest growth rates of value added, on the other hand - industrial chemicals and other 17 chemicals (13 per cent annual rate of growth) show very low employment elasticity. Similarly, electrical machinery has high value added growth but very low employment elasticity. On balance, it does not appear surprising that aggregate employment growth in industry or in manufacturing in South Korea over this period has been low to moderate. Within Asia, as we saw earlier, Malaysia appears to be something of a “tiger” at least in terms of employment generation in manufacturing, showing high aggregate rates of growth of manufacturing employment of around 7 per cent per annum. However, as is clear from Table 6, this does not reflect high elasticities of employment, which are fairly low in most sectors. Rather it is the result of sheer output and value added growth, which is evidently very impressive. The only two sectors which appear to combine high employment elasticity with reasonably high rates of value added growth are plastic products and professional and scientific equipment. It is interesting that across the Asian countries considered here, with a few manufacturing sectors in some countries as exceptions, the sectors that have been growing rapidly in terms of value added are those with low employment elasticity. Conversely, the sectors that generate more employment at the margin are those that have not been growing very fast in terms of value added. In some countries textiles and clothing are exceptions to this, in other countries, this is not the case. It is also interesting to note that the much-vaunted feminisation of employment which is widely seen to accompany export-oriented production, has actually been receding in many of the high-exporting countries of East Asia over the 1990s. This process, which has been documented and explored in Ghosh [1999] is one whereby there was a substantial increase in female share of employment in many of these economies in the period 1980-92, and subsequently female employment has tended to stagnate or even decline not only as a share of total employment but even in absolute terms. The causes for this process must be complex, but it is depressing to note that it has typically accompanied legal attempts to improve the conditions of women’s work as well as the reduction of gender wage-gaps in the Asian countries concerned. In other words, as the relative position of women workers became less inferior, they tended to become less attractive to employers seeking cheap and “flexible” labour. This was also associated with technological changes which increased the reliance on certain types of skilled labour as opposed to unskilled and semiskilled assembly line work. It may be worth bearing in mind that what appears to 18 have happened to women workers in East Asian export manufacturing can also happen to all Southern workers as a group in the international economy. In the countries of Central and South America that are considered here, the picture is even starker. Across almost all sectors, employment elasticities are at best very low and at worst quite substantially negative. Quite often, when they are positive, they are associated with negative rates of value added change. The only exception to this in Brazil comes in the wood products sector (scarcely a cause for celebration given the established relationship of this industry with the deforestation of the Amazonian rain forest). Even Chile, which currently is seen as the “success story” of Latin America, shows high employment elasticities in only a few sectors, and these are not necessarily always combined with high growth rates of value added. The details of specific countries and sub-sectors, while obviously of some importance, are for present purposes less relevant than the main conclusion that seems to emerge from an examination of these data. This is that the general perception, among both economists and policy makers, that the recent period has seen a significant expansion of manufacturing employment in developing countries as a consequence of greater international trade integration, does not appear to be warranted. Rather, the perception which is more widespread among trade unions, workers and people in general in developing countries, that job opportunities in manufacturing are not keeping pace with the expansion in the labour force and may even be declining in the aggregate, appears closer to the truth even in several of the most “dynamic” exporting economies. In other words, despite the evidence on relocation of a number of manufacturing industries and the increasing emphasis of multinational companies on the acquisition and use of assets in developing countries, in the net the North has not been exporting jobs to the South, or at the very least, the South is not a net importer of manufacturing employment. Instead, many manufacturing jobs may simply have disappeared somewhere in between... III What explains this pattern, which at first sight appears completely counterintuitive ? And where, indeed, have the manufacturing jobs gone ? Much of the debate, especially in the North, has focused on the relative significance of trade and technology, and attempts have even been made to quantify the individual significance of each of these factors. Some of this discussion may 19 obscure the larger process, in terms of the pattern of evolution of capitalism as a world system in the recent past, which has determined both of these processes and made them closely interrelated. Certainly, as far as developing countries are concerned, the dichotomy may not be a useful one, since it will be argued in this paper that both processes (of patterns of trade and of technological change) emerge from a more basic feature, namely the particular tendency of accumulation and concentration which characterises this phase of capitalist evolution. There are three immediate causes for the evident trend that has been described in the earlier section, that in the net, manufacturing employment in the South has not grown as much as could be expected from the increase in the Southern share of manufactured goods exports or the evidence of relocative FDI. The first cause stems from the fact that external trade for any country is obviously a two-way process. Just as the North has been importing more manufactured goods from the South than before, so too have Northern manufactured goods imports invaded Southern domestic markets. Indeed, over the past decade, the South on the whole has had a negative trade balance with the North, even in the realm of manufactured goods. There are therefore two simultaneous processes of relocation occurring : one of certain types of goods from Northern to Southern locations, and one displacing Southern domestic production with Northern imports. This process has been dramatically accentuated by the trade liberalisation measures which have been put into place in almost all developing countries over the past decade. The Northern perception has been that both forms of relocation in any case shift labour-intensive employment to developing countries and capitalintensive employment to developed countries. This is not always, or even usually, the case. Many of the newly deregulated imports into the South (produced, no doubt, by capital-intensive techniques in the North) displace small-scale and highly employment-intensive domestic producers who are equally unable to compete in international markets. In most developing countries, the consequent job losses have simply not been compensated for by expansion in export employment, even where exports have grown significantly. Thus, the net expansion in manufacturing employment becomes low or even negative because of the effects of import penetration. In this context it is worth noting that the single great exception to the relative stagnation of manufacturing employment in the South is the People’s Republic of China. This is a special case for many reasons, but also (in this context) primarily because so much of its industry still remains under State 20 ownership and control and it has so far done much less in terms of import liberalisation than other developing countries. In other words, even as there is a substantial expansion in export-oriented employment, job losses elsewhere in the economy have been contained to some extent because of employment in state enterprises and relatively controlled import liberalisation which still permits a range of domestic manufacturing to survive. Studies that extol China’s success in increasing employment in manufacturing without taking cognisance of this basic fact, may miss the point. It therefore follows that the future course of manufacturing employment even in China is not clear, if indeed, there is substantial import liberalisation as a result of joining the WTO, and if the declared “reform” of state enterprises actually does take place. The second factor in explaining the disappearance of manufacturing jobs is the fallacy of composition in export expansion. This is of course something that was well known in the development literature, but appears to have been forgotten in all the heady excitement about “globalisation”. The idea that all developing countries can use export expansion as the basis for more generalised economic growth was seen to be obviously problematic in the case of primary goods. But it was recently assumed that a more diversified export basket with greater emphasis on manufactured goods would do away with that problem. The experience of the 1990s shows that this is not the case. Thus, for example, the significance of the Chinese devaluation of the renminbi in 1994, in subsequently affecting the competitive exporting capacity of Southeast Asian economies and thereby contributing to the slowdown in exports which became one of the factors leading to crisis in the region in 1997, is now well known. The concentration of Southeast Asian export growth in certain sectors such as office equipment and consumer electronics meant that after 1996, the export success of certain countries (notably China and the Philippines) was enough to wipe out the export growth of almost all the other countries in the region, in these sector. [Ghosh and Chandrasekhar, 2001] As pointed out in UNCTAD [1999], more and more manufactured goods exports of developing countries are beginning to display the characteristics of primary commodity exports, including price volatility and low price and income elasticities of demand. It is this fallacy of composition argument which at least partly explains the very limited number of success stories in terms of net expansion in manufacturing employment, that was indicated in the previous section, despite the very large number of countries attempting to use export-orientation as the main basis for economic expansion. And then, of course, there is the entire issue of technological change which is increasingly labour-saving in nature. There is no doubt that such 21 changes are indeed taking place. Of course, labour-saving technological change is certainly not a new feature of capitalist investment and in fact is a basic property of most capitalist innovation. But it does appear to have become much more rapid and therefore more direct in its influence on employment, largely because the growth in volume of output is typically not large enough to make up for the decline in per unit labour use. It is important to remember that such technological change is equally evident across all countries, developed and developing. This is not only because to a very large extent the basic sources of all new technology are still the northern centres of capitalism. It is also true because the same forces which make capitalists seek labour-saving technology in the North operate in the South as well, notwithstanding the lower real wages that are commanded by workers in the South. It is this aspect of technological change which reveals what may be the deeper underlying cause of the processes that have been outlined in this paper. Many of the processes that have been described in this paper reflect fairly basic tendencies of capitalist accumulation, which have been evident to greater or lesser degree throughout its history. The difference is that now they appear in accentuated and accelerated form, thereby creating the impression of something rather new and different. But in fact they are substantively the same, and therefore this particular phase of capitalist evolution (which for summary purposes I will describe as the “globalisation” phase) is in many ways a recreation or an intensification of longer run tendencies of the system. One of the most basic of such tendencies is that towards concentration and centralisation. And it is no secret that the decade of globalisation has been marked by some of the strongest and most sweeping waves of concentration of economic activity that we have known historically. This has been ably documented elsewhere [e.g. Epstein 2000] and is now so obvious that there is no need to belabour the point. But what is important for present purposes is the effect this wave of concentration and centralisation, which is taking place internationally and within national boundaries as well, has on patterns of manufacturing employment. There are at least four significant ways in which the concentration process negatively affects productive employment generation in the manufacturing sector, and why it causes jobs to disappear in both North and South. The first is the fact, first noted by Marx and then documented by Lenin, but certainly just as relevant today, that periods of high concentration are also periods of the intensification of competitive pressures. The intensification of competition in turn means that the “normal” tendencies of capitalist 22 accumulation are sharpened and aggravated, including the pressure to find more and more means of reducing labour costs, for example. There is intensification of competition not only between capitals but also between countries as a result of the concentration of international capital. This is reflected in governments vying with each other to provide incentives for capital that plays increasingly hard to get, by providing tax sops, fiscal carrots including guaranteed rates of profit, as well as various other incentives. It also means that workers are told to become “flexible” enough to make themselves sufficiently attractive to be hired by choosy employers. It is precisely that concentration of capital in relatively few hands that makes threats of withdrawal so plausible and the need to placate such large capital more imperative. The third effect of concentration that has relevance for employment is that it involves the amalgamation or destruction of smaller capitals. Thus, the very processing of the big swallowing up the small, at both national and international levels, tends to reduce employment. So the reorganisation and restructuring of production takes the form of the decline in importance of smaller more employment intensive manufacturing units and the growing dominance of large players who employ much fewer people. Associated with this are the well known stagnationist tendencies of monopoly capital, which also tend to reduce employment indirectly through their effect on aggregate demand. Finally, the concentration of finance capital, which plays such a dominant role in the international economy today, also contributes to the overall stagnationary tendencies in the manner outlined by Patnaik [2000], not least by constraining the ability of nation states to intervene to shore up domestic demand and provide more egalitarian distribution. This also inevitably affects employment generation in a negative way. The central argument of this paper can be briefly summarised as follows : The perception that the Northern core capitalist countries have been “exporting” jobs in the net to Southern countries is not borne out by a cursory examination of employment trends in even the most dynamic of Southern exporters taken as a group. While manufacturing jobs may have disappeared from the North, they have not reappeared equivalently in the South. It is true that there has been production (and employment) relocation in a number of manufacturing sub-sectors which are typically described as more labourintensive. But in most countries this has been more than offset by decline in other sectors of manufacturing that have been hit by import competition, or 23 the nature of the export-oriented manufacturing itself has been such that employment elasticities of new production are low. As a result, the increase in manufacturing employment has been confined to a very small subset of countries, and even here many sectors do not show the expected dynamism in employment generation. It is further being argued that this pattern is the result of three factors. First, the trade liberalisation which has exposed manufacturing production in developing countries to import competition and thereby eroded a large amount of traditional activity or recent import-substituting production, much of which was relatively labour-intensive. Second, the problem of fallacy of composition in exports, which has not allowed more than a minuscule number of countries to benefit substantially from access to Northern markets. Third, the pattern of technological innovation which has contributed in no small measure to the low and declining employment elasticities of production in exporting sectors as well as in other activities. The position taken here is that all of these factors are themselves the consequence of a larger process of national and international concentration and centralisation of production. This works directly in a number of ways to reduce the potential for employment expansion in developing countries. It involves the assimilation or destruction of small capital that uses more labour per unit of output, by larger capital that effectively reduces employment. It increases competitive pressure - across countries and capitals - that increases the quest for reducing labour costs in a variety of ways. It inhibits governments from undertaking expenditures that could directly and indirectly increase employment and economic activity in the system as a whole. If this argument is correct, then both the pattern of trade and the technology changes that have characterised the globalisation phase of capitalism emanate from (and of contribute to) the basic process of concentration of capital that has especially marked this phase. This means that solutions to the problem of disappearing jobs in turn cannot be found in the specifics of trading patterns or even forms of technological innovation, but in the need to curb and contain the power of large capital. References Burke, James and Gerald Epstein [2000] Threat effects and the internationalisation of production, Paper for IDPAD Conference on 24 “Globalisation, structural change and income distribution” Chennai, 14-17 December 2000. Feenstra, Robert [1998] “ Integration of trade and disintegration of production in the global economy”, Journal of Economic Perspectives, Fall, Volume 12 Number 4. Freeman, Richard B. [1995] “Are your wages set in Beijing ?” Journal of Economic Perspectives, Volume 9 Number 1, Winter. Freeman, Richard B. and L. Katz [1995] Differences in wage structure, University of Chicago Press, Chicago. Ghose, Ajit [1999] Trade liberalisation and manufacturing employment, Employment Paper 2000/3, International Labour Office, Geneva. Ghosh, Jayati [1999] Trends in economic participation and poverty among women in the Asia-Pacific region, ESCAP Bangkok, also available at http://www.macroscan.com. Ghosh, Jayati and C. P. Chandrasekhar [2001] Crisis as conquest : Learning from East Asia, Tracts for the Times, Orient Longman, New Delhi. Krugman, Paul [2000] “Trade, technology and factor prices” Journal of International Economics, Volume 50 Number 1. Leamer, Richard [2000] “What’s the use of factor contents ?”, Journal of International Economics, Volume 50 Number 1. Patnaik, Prabhat [2000] “Money, finance and the contradictions of capitalism”, Paper for IDPAD Conference on “Globalisation, structural change and income distribution” Chennai, 14-17 December 2000. Rodrik, Dani [1997] Has globalisation gone too far ? Institute for International Economics, Washington. Singh, Ajit and Rahul Dhumale [2000] “Globalisation, technology and income inequality : A critical analysis”, Paper presented to IDPAD Conference on “Globalisation, structural change and income distribution” Chennai, 14-17 December 2000 25 van der Hoeven, Rolph and Lance Taylor [2000] Structural adjustment, labour markets and employment : Some considerations for sensible people”, Journal of Development Studies, Vol 36 No 4 UNCTAD [1999] Trade and Development Report, Geneva. Williamson, Jeffrey G. [1998] “Globalisation, labour markets and policy backlash in the past”, Journal of Economic Perspectives, Volume 12 Number 4, Fall. Wood, Adrian [1994] North-South trade, employment and inequality : Changing fortunes in a skill-driven world, Oxford : Clarendon Press. Wood, Adrian [1998] “Globalisation and the rise of labour market inequalities”, Economic Journal Volume 108, September. 26