Cutting the Daubert knot

advertisement

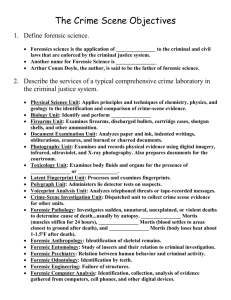

Daubert in the UK – Second order evidence between courts and commissions. Burkhard Schafer, C.G.G. Aitken, D. Mavridis, Joseph Bell Centre University of Edinburgh 1. Introduction This paper analyses some of the conceptual and procedural issues that are raised by the gradual reception of the US Daubert ruling in the UK. We will discuss not so much the use of the Daubert criteria by the UK courts, but by the Criminal Cases Review Commissions and other extra-judiciary bodies, which are a unique feature of the British criminal justice system. From the work of Alan Watson on legal transplants, we know that the transfer of a legal concept across jurisdictional boundaries can sometimes have unforeseen consequences. A transplanted legal concept can develop in its host environment features that are very different from those it displayed in its original context. One question we try to address is whether using the Daubert criteria not as a pre-trial filter for expert evidence by courts, but as a standard of post-conviction scrutiny by commissions not made up entirely of lawyers. Does this new type of usage, outside the formal court system, address some of the problems of Daubert that have been identified since the ruling was made in 1993, or does it create new problems and issues? Does it change the internal logic of the Daubert criteria, and if so, for the better or for the worse? Conversely, we will analyse if this US import changes the dynamic between courts and commissions. Building on the work by Duff, we will use a system theoretical framework to argue that the issues he first identified in the field of witness evidence are bound to return with a much sharper focus in the field of expert evidence if, as has been suggested, the Criminal Cases Review commission establishes a scientific subcommittee that will apply Daubert scrutiny to trial evidence post conviction. We will argue that the use of these criteria will give considerably new strength to his contention that the CCRCs are indeed a new type of “Grenzstelle” or border control between law and science, whose workings cannot be adequately explained by legal conceptualisations alone. We will focus on one particular type of expert evidence, on what we term “second order evidence”. With this we mean those forms of expert evidence that help to interpret and determine the evidential weight of other evidence. An important example of second order evidence is evidence by statisticians on the probative weight of forensic evidence such as DNA evidence. Other examples are psychological evidence on eyewitness credibility or possibly evidence by professional epistemologists on the scientific validity of a forensic discipline that has been used to adduce “first order” evidence such as fingerprint evidence or evidence from forensic linguistics. In legal systems whose rules of evidence have evolved around the trial by jury, such second order evidence has traditionally had a precarious existence, always in danger of intruding into the jealously guarded territory of the jury. Since however proceedings before the commissions are not jury trials, it is here that we can expect the most significant discrepancies between trial rules and commission rules on admissibility to occur. 2. The Criminal Cases Review Commissions and Daubert So far, the UK has been hesitant to follow the lead that the US has taken in the Daubert decision to regulate the admissibility of scientific evidence. While some British courts have expressed their belief that UK and US law in this field are now converging, closer scrutiny reveals a considerable distance in approach. However, the need for greater scrutiny of scientific evidence is just as acutely felt on this side of the Atlantic as it was in the US. Over the past decade, a string of high profile criminal cases has brought the often problematic role of forensic science to the attention of a wider audience. In 2003, Sally Clark had her conviction for child murder overturned, after crucial flaws in the evidence of the main prosecution expert, Sir Roy Meadows, were found. Three more women were cleared of the same offence, convicted on the same flawed evidence. At the heart of the problem was the assessment of the statistical significance of the medical results reported by the medical expert, whose interpretation of his findings were challenged by professional statisticians. In 2006, Shirley McKie was awarded £750000 for her wrongful conviction based on flawed fingerprint expertise. In 2007, Sean Hoey was acquitted from the charge of being responsible for the Omagh bombing when the judge cast doubt on the reliability of two types of forensic evidence presented against him, most prominently the use of Low Copy Number DNA, a technique solely used by the English Forensic Science Service and rejected by other police forces worldwide. In the 1980s, a string of similar miscarriages of justice, mostly in relation to IRA terrorism, resulted in an overhaul of police practice and procedure, and the creation of a unique British legal institution, the Criminal Cases Review Commissions (CCRC). When in the 1980s, the emphasis was on police misconduct, more recent cases have cast a glaring light on the reliability of forensic science. However, with the English and Scottish CCRCs well established and enjoying high public confidence, it seemed an obvious choice to utilise them also in the current crisis. In 2005 the House of Commons Select Committee on Science and Technology issued its report Forensic Science on Trial,1 which made explicit reference to the Daubert criteria. It recommended to cerate a new Forensic Science Advisory Council ’to oversee the regulation of the forensic science market and provide independent and impartial advice on forensic science’ (recommendation 11), a forum for Science and the Law (which may be subsumed into the Forensic Science Advisory Council) recommendation 51) and the establishment of a Scientific Review Committee within the Criminal Cases Review Commission (recommendation 57). On Daubert, the report states: “The absence of an agreed protocol for the validation of scientific techniques prior to their being admitted in court is entirely unsatisfactory. Judges are not well-placed to determine scientific validity without input from scientists.: We recommend that one of the first tasks of the Forensic Science Advisory Council be to develop a “gate-keeping” test for expert evidence. This should be done in partnership with judges, scientists and other key players in the criminal justice system, and should build on the US Daubert test” (para 173). Is this legal transplant going to change the dynamics of the Daubert criteria when finally applied in the UK? Are committees as gatekeepers outside the trial process the answer to the critical questions raised by epistemologists and legal theorists commenting on Daubert? These are the questions this paper tries to address. We will use as example the question of the admissibility of statistical and probabilistic “second order” evidence. The Daubert ruling is in an interesting way ambiguous about statistical expertise. On the one hand, the requirement to report known or potential error rates lends itself to probabilistic assessments of forensic results, such as 1 http://www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm200405/cmselect/cmsctech/96/96i.pdf those commonly used for instance in DNA evidence. But statistics itself does not pass the Daubert test. As a structural, not empirical science, it is neither falsifiable nor can it be in any meaningful sense tested (Kaye 2005 478). This assessment seems to support the traditional reluctance of UK courts to admit evidence by experts in statistics, which as been seen as problematic attempt to usurp the jurors’ prerogative to weight the evidence offered to them. However, it can lead to the paradoxical conclusion that after Daubert, we should expect more evidence of a statistical nature being led, but only as part of the “primary” scientific evidence itself, and therefore typically offered by scientists who are not experts in statistics. Just how problematic this development would be becomes apparent if we look again at the Sally Clark case. After her conviction was finally referred back to the courts by the CCRC and eventually quashed, the medical expert in turn found himself the subject of legal proceedings, starting with a misconduct charge by his professional body, the General Medical Council. Part of the case against him was that in offering a statistical evaluation of his findings, he strayed outside his core competency. While his conviction by the GMC was later successfully challenged in court, the right of the GMC to sanction members of the medical profession for offering statistical evidence outside their core competency was affirmed by the courts. Rom this, the following problematic picture emerges: Courts encourage, and in some cases even insist, on statistical assessments of certain types of forensic evidence, provided it is given by the forensic expert, but are reluctant to admit independent statistical expertise by professional statisticians. The CCRC however uses just that type of evidence for post conviction scrutiny and can and will refer case back to the courts if the statistical evidence was flawed. The expert then may face sanctions by his professional body for doing what the trial judge encouraged, that is offering a statistical evaluation of his evidence. We will in the next step of our analysis briefly discuss the present state of the law on expert testimony in the UK in more detail. This will be followed by a brief introduction of the rules of evidence that govern the CCRCs in particular the Scottish CCRC. We will discuss in particular the relation between the Scottish CCRC and the appeal courts regarding the question of evaluation and interpretation of evidence. A system theoretical perspective will then allow us to see the issues raised by Daubert and the debate surrounding the evidentiary autonomy of the CCRC as two sides of the same coin. Both are attempts to open up the normatively closed legal system to scientific rationality, Daubert by “drawing in” scientific rationality into the rules of evidence in a court room setting, the CCRC by “pulling out” the issue of (scientific) evidence evaluation from the legal-procedural environment into an epistemic setting that comes closer to scientific investigation. Both are only partially successful, but partial success may be the only thing that is achievable if we want to stay true to the inner logic of scientific rationality and the internal logic of legal procedure at the same time. 3 Admissibility of scientific evidence in the UK: between courts and commissions In marked contrast to the law of the US, English and Scots law have traditionally refrained from imposing too exacting a standard on the methodology or reliability of expert testimony. The role of the expert witness was clarified in a Scottish case. Their duty is to furnish the judge or jury with the necessary scientific criteria for testing the accuracy of their conclusions, so as to enable the judge or jury to form their own independent judgment by the application of these criteria to the facts proved in evidence. (Davie v. Edinburgh Magistrates, 1953.) An English case, over twenty years later, provided additional ideas as to the role of an expert witness and the admissibility of expert evidence, in the context of psychiatric evidence relating to the defence of provocation. An expert’s opinion is admissible to furnish the court with scientific information which is likely to be outside the experience and knowledge of a judge or jury. If on the proven facts a judge or jury can form their own conclusions without help, then the opinion of an expert is unnecessary […] Jurors do not need psychiatrists to tell them how ordinary folk who are not suffering from any mental illness are likely to react to the stresses and strains of life. It follows that the proposed evidence was not admissible to establish that the defendant was likely to have been provoked […] We are firmly of the opinion that psychiatry has not yet become a satisfactory substitute for the common sense of juries or magistrates on matters within their experience of life. (R. v. Turner, 1975.) A perception of “general helpfulness” (with the possible corollary that obviously contested expertise is “unhelpful”), and staying outside the core territory of the jury , are as a result the only two limitations on the admissibility of scientific expertise. Lack of scientific credibility is considered mainly a question of weight, not of admissibility. However, some more recent decisions indicate a possible willingness to increase the scope for the judges to scrutinize expert evidence. A decision in point is R v Gilfoyle. In this case, the defence had offered in evidence a “psychological autopsy” of the alleged murder victim, to substantiate the defence claim of a suicide. In ruling inadmissible this “psychological autopsy”, the Court of Appeal indicated a willingness to impose a higher levels of scrutiny of expert evidence than was previously the case. Quoting approvingly Frye, the judges ruled that “psychological autopsies” were not a technique that was generally accepted in the relevant scientific community, and hence inadmissible. The judges arguably did not realise, or did not care, that Frye is no longer the prevailing view in the US. In R v Dallagher, the judges went one step further. Discussing the issue of earprint identification, the Court of Appeal for England and Wales compared explicitly US jurisprudence with the current English law in this area, and concluded that the two are now broadly similar (O’Brien 2003). This conclusion however is only tenable if the difference between Daubert and Frye is downplayed to such a degree as to make Daubert all but redundant. A much more liberal approach to the admission and presentation of dubious expert testimony than in the United States remains a distinctive feature of UK law both south and north of the border. The dangers of such a liberal approach have increasingly been recognised, not the least after the string of high profile miscarriages of justice caused by problematic scientific evidence mentioned above. As already indicated, one proposal wants to utilise a mechanism to prevent miscarriages of justice that was established when a string of wrongful convictions, mostly of people suspected of links to IRA terrorism in 1997 (see e.g. Nobles and Schiff 2000; Walker and Starmer 1999; Belloni and Hodgson 1999). Implementing a key recommendation of the Royal Commission on Criminal Justice,2 the Criminal Cases Review Commission was established as a “remedy of last resort” (Duff 2001), covering cases from England, Wales and Northern Ireland. Two years later, a second such body, the Scottish Criminal Cases Review Commission, was created on recommendation of the Sutherland Committee. We will focus in our discussion on the Scottish Criminal Cases Review Commission, which, as Duff convincingly argues, has a somewhat wider remit, and a greater independence from the courts, than its English counterpart (Duff 2002). The SCCRC is “independent of Government and of the Courts”. In deciding whether or not to refer a case back to the courts, it also has considerable investigative powers of its own. However, it does not have the authority to vacate decisions directly, and the final say is always with the relevant Court of Appeal, which remains the only body with the power to quash a conviction. This lack of autonomous power to quash convictions has led some commentators to conclude that the Commission is in a position of “basic statutory subordinance” or “ deference” to the Appeal Court. This would place them firmly within the “normatively closed” legal system (Nobles and Schiff 2000). The Commission, in this view, has to “second guess” the court of appeal’s approach to the case in question (Taylor 1999 236), and is as a result “indirectly“ bound by the court’s rules of procedure. If the commission were to base its 2 The Royal Commission on Criminal Justice, 1993, Cmnd. 2263, Chap. 11 referral on evidence that would be inadmissible in at appeal court, the court could not but to confirm the earlier decision. If this analysis were correct, it would become questionable why a “Commission approach” was chosen in the first place. Instead, a more obvious solution would have been simply to allow for further appeals within the established court system. This would have brought the UK in line with other common law countries, most notably the US, whose appeal structure is far more developed than that of England or Scotland (Griffin 2001 1267ff). For the English CCRC, this reading seems however the more compelling. It may only refer cases to the appeal court of there is a “a real possibility” that the conviction would not be upheld – with other words, its very remit invites the English CCRC to consider the likely opinion of the appeal court. The Scottish CCRC by contrast is under no such restrictions. It is empowered to refer a case if it is has concluded (a) that “ a miscarriage of justice may have occurred” and (b) that it is “ in the interests of justice” to reopen the case. Duff concluded that the precise role of the CCRC, and especially the extend to which they seen themselves bound by the law of evidence, remain ambiguous (Duff 2001 362). However, far from being a shortcoming, this ambiguity is the intended consequence of having a body that is “neither wholly within nor wholly outwith the criminal justice system” (Duff 2002 363). For Duff, they are “ cross-border institutions, bridging the gap between the formal processes of criminal justice and wider political and social institutions.” With the proposal by the Select committee, they will also become a bridging institution between scientific and legal modes of rationality. The recent proposal to integrate within the CCRC a body responsible for the scrutiny of scientific evidence gives further support to Duff’s contention that the sole concern of the CCRC should be the reliability of the evidence that has been submitted, not the demands of procedural propriety (Duff 2001 391). Duff discusses in his article several problematic scenarios where the assessment of the Commission of the reliability of the evidence for and against the accused and the rules of procedure are in potential conflict. Examples are for instance facts that could have been raised in the first instance trial, and there are no sound explanations why they were not. The situations that concern us here are potentially less problematic, but nonetheless examples of divergence between the evidentiary rules of the trial and the post conviction scrutiny of the evidence by the CCRC. If the Commission, as proposed in the House of Commons Report, develops its own criteria for scrutinizing expert evidence, using rules similar to those proposed in Daubert, two further scenarios become possible: a) The Commission can decide that evidence that met the liberal standards used by the courts does not meet its more exacting standards, and b) the Commission may use “second order” evidence which would not be considered competent by the trial courts to decide that either a scientific theory, or the application of this theory in the specific case, was unreliable or insufficient to warrant a conviction. Despite the generally very liberal approach to scientific expert evidence in the UK, “second order evidence”, evidence that helps to evaluate other evidence or put it into perspective, has seen more strenuous objections. We have already seen in the quote from Turner that evidence about “ordinary people”, even if offered by a professional psychiatrist, is deemed to be within the ken of the average juror. Similarly, “second order evidence” by psychologists or cognitive scientists on eyewitness evidence is generally inadmissible in the UK. (Turner (1975) 60 Cr App R 80 at 83; confirmed in Chard (1971) 56 Cr App R 268; R v MacKenney and Pinfold (1981), see also Roberts 2004) With statistical evidence, the picture is more complex. As already indicated above, Daubert presents a potential ambiguity regarding the issue of genuinely probabilistic or statistic evidence. The UK situation regarding statistical evidence is unsettled. We alluded above to the Sally Clark case. In R v Clark, adjudicated eventually by the Criminal Cases Review Commission, a conviction was quashed and the crown expert, Sir Roy Meadows, eventually disciplined by his professional organisation precisely because he failed in his professional duty when as an expert witness on sudden infant death, he strayed into the territory of the statistical expert and offered a quantification of his evidence in probabilistic terms that turned out to be mistaken. At the same time, courts have rejected probabilistic evidence, at least in the form of general statistical evidence, as intruding illegitimately into the territory of the jury (R v Denis Adams 1998), strongly encouraged the inclusion of such statistical evaluation in certain forms of forensic evidence, in particular DNA evidence, though again presumably not lead by professional statisticians (R. v Doheny and Adams 1997) and put forward criteria that statistical evidence has to meet if it is offered to evaluate more speculative forensic disciplines after all (in R. v. Grey 2003). Since the CCRC is less constraint in the type of evidence that it uses to decide if a miscarriage of justice may have occurred, professional epistemologists, cognitive scientists (on eyewitness evidence) or professional statisticians could all be employed to decide the safety of a conviction. In particular, the commission could use professional statisticians in its investigative work to quantify the evidentiary value of evidence presented at the trial stage and beyond. Following on from the Daubert criteria, this evidence could either take the form of a Bayesian analysis of the probative value of a piece of evidence assuming that the underlying scientific theory is sound, or indeed provide expertise on the degree that a scientific theory has been corroborated. Both the Daubert requirements of establishing known error margins and only using “ tested” theories could be developed into probabilistic assessments. More unusual, and potentially more controversial, would be to emphasise the “Hempel aspect” (Haack 2001) of Daubert and incorporate more recent formal developments in confirmation theory. In Betting on Theories, Maher argues that probability theory, and in particular Bayesian theory, has an important role to play in deciding whether or not it is rational to believe in a scientific theory. In a shift of emphasis similar to the one proposed for Daubert by Kaye, the question is not longer whether or not a theory is “formally” scientific, but rather “when it is rational to accept a scientific theory for the purpose of decision making?”. Elaborating the views of Ramsey and Savage, Maher’s approach would offer a decision-theoretic derivation of principles for the revision of probabilities over time, combining a Bayesian decision-theoretic account of rational acceptance with confirmation theory. While both types of probabilistic (re)assessment of evidence would go significantly beyond Daubert scrutiny as it is currently understood in the US, they would stay true to the spirit of the CCRC while extending the underlying ideas of Daubert in a natural way. The role of the CCRC is to form an opinion on whether a miscarriage of justice may have occurred – and what better way for assessing this possibility than through an assessment of the probative weight of the evidence proffered in a rigorous formal setting. The normal objection that such type of evidence trespasses into jury territory does not apply to the CCRC, which carries out its own independent research and is therefore not conceptually restraint by the division between presentation and evaluation of evidence. We have argued that probabilistic second order evidence, following Daubert in spirit if not in letter, can take two forms. One is the evaluation of the probative weight of a piece of evidence assuming that the scientific framework that governs its interpretation is sound. This type of analysis is already common in DNA cases, and expands on the Daubert criteria to demand and use known error rates for the evaluation of evidence. The more ambitious project replaces the qualitative Daubert criteria - “has the theory been tested?” - with a quantitative assessment of how the verified consequences of a theory have increased or rational belief in its truth (Maher 2004). In the context of the CCRC, this gives rise to two potentially interesting scenarios. The CCRC is not restricted to decide of at the time of the original trial, reliance on a proposed scientific theory was justified. Rather, it can take all further tests that have been carried out after the original decision was reached into account. Furthermore, while only the accused can appeal to the CCRC, the CCRC is not restricted to consider only new evidence favorable to the accused. As Duff argues, its commitment is to the truth, no procedural fairness. A possible outcome of the assessment of a contested expert opinion could therefore be that while at the trial, the theory was insufficiently tested to warrant the decision of the jury, more recent tests of the theory have confirmed its validity to a sufficient degree. Conversely, it can decide that while at the time of the trial, a theory was sufficiently corroborated, new tests have cast doubt on its validity while falling short of actually falsifying it. In this case, the CCRC ought to refer the case back to the court of appeal. This openness to new confirming or detracting evidence, which is not constraint by any time barriers, creates an open ended process of scientific scrutiny which, as we will argue in more detail below, not only takes account of the “pastoriented” criteria that a theory should have been tested, but also in an important sense the “future oriented” criteria that acknowledges the falsifiability of truly scientific theories. From the perspective of the trial court operating in the shadow of the CCRC, any decision on the reliability of a proposed scientific theory is at the point of decision making justified by its past corroboration though testing, but also open to both confirming and weakening future tests. Assume now the following scenario: At the trial stage, evidence from a relatively new forensic discipline is led. The CCRC decides that this evidence was unreliable, based on statistical evidence that concludes that at the time of the trial, the scientific discipline in question while both formally falsifiable and to some extend “tested”, was nonetheless insufficiently corroborated by these tests. The issue now arises if the appeal court, which would not normally accept such second order expertise, can take nonetheless the findings of the CCRC directly into account. There are no principled policy reasons, nor obvious fair trail requirements, why it should not do so. This sets our case apart from the situations discussed by Duff, whose examples typically involved evidence uncovered by the Commission that would have been inadmissible at trial due to sound policy reasons. It does raise however quite intricate conceptual issues. If the appeal court were to accept the recommendations of the CCRC, would it by implication change the rules of evidence also for the trial stage? Or could it take account of the CCRCs finding, but somehow replace its second order evidence by something that looks more like new, “primary” evidence? As we will argue below, the CCRC has the potential to engage with scientific modes of inquiry unencumbered by the logic of the trial. If however appeal courts then refuse to base their decision on the Commission’s finding, the problematic question of how to translate scientific rationality into legal rationality, one of the main objectives of Daubert, is simply postponed, but not resolved. 3. Evaluation When the court in Daubert attempted to identify a demarcation criteria that would enable future judges to distinguish science from non-science, the response of professional epistemologists to this intrusion into their territory was fierce and unforgiving: The Daubert court, so for instance Susan Haack, had been guilty of “mixing up its Hoppers and its Pempels” (Haack 2001) in a decision that was described as replacing “a judicial anachronism with a philosophical one” (Allen 1994). Does this mean that the UK, by no means alien to evidentiary anachronisms, adds now a philosophical one to its repertoire? Or does the use of extra-judicial commissions instead of the courts solve some of the internal conceptual tensions from which Daubert suffers? When two closed systems such as law and science interact, “errors in translation” are to be expected. While systems are cognitively open, they are normatively closed. This means that while concepts can travel across system boundaries, they are restructured and reorganised by the recipient system according to its own logic and normative structure However, not every simple mistake or misunderstanding deserves to be elevated to an example of system theory. Was the conceptual mix between Popper’s and Hempel’s theories then an inevitable consequence of law as a system trying to come to terms with scientific rationality, or was it a simple mistake by individual judges? If the former is true, then we have to abandon or at least to reformulate the attempt of the rationalist tradition in evidence scholarship to describe evidentiary reasoning in law as a natural continuation of scientific rationality, constraint, if at all, by rules of procedures that protect values other then the discovery of the truth and easily identifiable as such. Instead, we would have to establish how rules intended to establish the truth under the conditions of the trial with necessity differ from those commonly accepted by our best theories of science. Rules of procedure, including the Daubert rules, could then be reconstructed as attempts to “achieve to rationality under difficult circumstances”, establishing a legal theory of rational argumentation as opposed to a rational theory of legal argumentation. In this final section we will argue that there are indeed systematic differences between legal rationality in the fact-finding process that cannot be easily aligned with scientific modes of rationality. In the first part of our analysis, we want to substantiate our claim that scientific expert evidence takes place in a necessarily troublesome environment. We have argued elsewhere that trial rationality and scientific rationality differ in one crucial aspect. Scientific rationality presupposes a community of researchers with equal access to truth and the means to discover it, their relation is essentially symmetrical. The trial by contrast takes place in an environment where the parties have asymmetrical access to both truth and means of proof. (Schafer 2008). In a nutshell, premodern ‘science’ was characterised by asymmetric access to the truth. Certain authorities (the church, Aristotle, the Bible) were deemed to have privileged access to the truth, appeal to authority therefore was a legitimate argumentation scheme. Modern science, and its philosophical counterparts of enlightenment and empiricism, replaced this asymmetrical, inegalitarian model by a symmetrical, egalitarian model of fact finding: Through our senses, we all have equal access to the one shared reality. From this it follows that every idea has to be subjected to the public forum of reason where everybody can be participant, and everybody has in principle an equal ability to establish the truth. Since the participants in this scientific discourse are freely interchangeable (i.e. it does not matter who makes an observation) intersubjective agreement over the facts is both possible and desirable at least as a limiting ideal for rational deliberation. (Habermas 2003) Honest disagreement is simply indicative that not all possible observations and tests have yet been carried out. Scientific rationality is premised on an open ended process of criticism and confirmation; it does not matter who proposes a theory, if it cannot be replicated by everybody else at least in principle, its truth claim is invalid In the trial context however, one of the disputants has privileged access to the truth: Apart from highly unusual situations such as sleepwalking or serious mental illness, the defendant will know whether or not she committed the actions in question (though of course not necessarily their precise legal significance). No argument by the prosecution, regardless how convincing, will persuade her otherwise. Indeed, we would consider it deeply irrational if they did. The converse is of course not true: The defendant may well convince the prosecution of her innocence. While the accused has privileged access to the truth, knows what has really happened but may not be able to prove it, the prosecution has privileged access to the means of proof. They command over the resources of the police and typically the state run forensic laboratories. More important though than this imbalance in resources are ‘temporal’ asymmetries between and prosecution. These are best explained by another example. In the investigation of the murder of Jill Dando, a famous UK TV presenter, a crucial piece of evidence was a minute speck of gun power residue.3 This was collected by the police and analysed by forensic experts. Because of the small size of the sample, the very process of testing destroyed it. This means that the tests cannot possibly be repeated. You only have one go at a crime scene, and often also only one go at the evidence collected there. Because prosecution/police and defendant are involved at different times in the process, they have with necessity different epistemic access to the facts. While rules of procedures can minimize the impact of this, for instance through requirements to document investigative actions taken, and by threatening sanctions for misbehaviour by investigator or prosecution, it is inevitable that ultimately an element of trust is required. Once again, this necessary assumption of trust is asymmetrical: in a criminal trial, we need to trust the assertions of the side more that has the less reliable, merely indirect access to the truth. These asymmetric distribution of access to truth and access to facts have a profound impact on the nature of scientific expert evidence. In a trial situation however, these preconditions are not met, appeal to the authority of the expert and trust in the system is inevitable, intersubjective agreement that 3 For more background see http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/programmes/panorama/7067290.stm includes the defendant not always a possibility even in principle. This presents a small paradox: Modern trials rely more and more on scientific evidence. But the way scientific evidence is presented in court, by an expert whose assertions can to some extend be scrutinised, but not replicated or tested by the audience, with necessity violates some of the conditions that are normally presupposed in scientific inquiry. For legal contexts too, the ultimate aim are intersubjectively verifiable results as a requirement for the rational acceptability of trial outcomes. It is a basic tenant of justice that the results of a trial should be intelligible to all parties involved, hence the rules that excuse those too mentally ill to understand the process from criminal responsibility. This then means that reasoning about facts in a criminal trial is different from other modes of rationality, due to the asymmetric distribution of knowledge and means of proof. An important function of the rules of procedure is to mitigate this inevitable tension between the modern ideal of rational inquiry and the constraints of the trial situation. Asymmetric allocation of the burden of proof for instance can be understood as a response to the asymmetric availability of means of proof. Rules on pre-trial disclosure can equally be seen as an attempt to create artificially, though legal fiat, a “common shared reality” between prosecution and defence that makes their debate more similar to symmetrical scientific investigation than would otherwise be possible in the asymmetric setting of the criminal trial. Where does this discussion leave Daubert? The Daubert ruling too can be seen as such a “bridging attempt”, bringing the rationality (and the authority) of scientific discourse into the structure of the trial process. Since the open ended, symmetrical process of scrutiny and critical investigation that is the hallmark of modern science cannot be fully replicated in the court room, it aims for the “second best”. Stein has argued that the function of evidentiary rules is often to achieve the “second best” when the best is not achievable under the constraints of the trial (Stein 2001). Similarly, Daubert can be read as establishing conditions for a non-scientific use of scientific knowledge that preserves as much of scientific rationality as possible. For our purpose, this means that Daubert does not so much establish a criteria to distinguish science from non-science. Rather, it gives rational conditions for the acceptance of theories under the limiting conditions of the trial. First, we note that Daubert is a “synchronically symmetrical” rule in the sense that it affects all parties equally. This seems to correspond to the equally symmetrical scientific rationality. However, it ignores the asymmetrical access to information that sets legal and extra-legal fact finding apart. As a result, while “syntactically” formulated as a symmetric rule, its effect is to reinforce the epistemic inequality between the parties. More difficult to analyse is the problem of “diachronic asymmetry”. Courts have to reach a decision at a given moment in time. Following again Maher, this means that they have to “take a bet” on whether the scientific theories that underpin the evidence are sound. Such a bet is rational if a theory has been tested to a sufficient degree – this is the Hempel aspect of Daubert, a “past oriented” criteria that aids the decision on whether to accept a theory for the time being or not. However, such time dependencies are alien to the self-understanding of science. Scientific theories are not normally formulated with temporal indices – they make statements that claim to be universally true, for all times at all places. Popper took this insight right to he heart of his theory, and most epistemologist after him, even when they disagreed with his specific account of scientific discover, followed him in acknowledging that where there is an unresolved debate between conflicting scientific theories, the future, not the past will have the decisive say. Lakatos in particular includes in his account the notion of “progressiveness” of good science: the scientific theory to back in such a dispute is the one that will allow in the future new to establish new laws (theoretical progression) or new, yet unforeseen applications to established laws (empirical progression). We can now see these tensions working out in the issue that Haack identified, the problematic use of Popper’s concept of falsification and indeed any other “future oriented” criteria. Law and science can be understood as systems in the sense of system theory. Systems are cognitively open, yet normatively closed. That means exchange of information is possible, but subject to distortions as the recipient system tries to “£fit” incoming in formation into its normative structure. As Popper made clear in the reply to his critics, the syntactic feature of “falsifiability” is indeed a trivial, logical insight. What is much more important to him is the normative implication of this syntactical feature. Falisfication is the way scientists ought to behave: accept that science is an open ended project, that “the future is open”, embrace critical analysis and as a corollary reject any type of authoritative statement. This strong normative dimension becomes particularly obvious when we look at the way in which Popper transferred these ideas to hs discussion of political institutions. There to, so he argues, an open process of inquiry and criticism is the best way of deciding social disputes. The rational and the social good meet in his ideal of the “ open society” for which the open scientific community is the blueprint. Expert lead reasoning about facts on court as we have argued is violating all these normative precepts of good scientific conduct with necessity. Consequently, the system of law in Daubert strips Popper’s account of scientific rationality of its normative aspects and recasts it in terms of the internal logic of the trial: While the law cannot wait for future scientists to settle disputes about the reliability of theories, it can make the factual assessment if a theory is syntactically formulated in such a way that such future scrutiny is – from the perspective of the present, - possible. What remains is the cognitive aspect of his concept of falsifiability. However, as Kaye notices, as a constraint on acceptable scientific theories, this criteria is so weak as to be virtually meaningless, especially when taken together with the requirement that a theory has already survived at least some attempts of falsification. The Daubert judges then were not so much confusing their Hempel and Poppers, rather, they tried to recast both in such a way that the normative logic of the trial remained intact, while preserving as much of the cognitive content of these theories as possible. Does the British proposal to use the Daubert criteria by commissions that operate outside the formal trial system change this assessment? First we note that the rules governing appeals are neither fully symmetrical nor asymmetrical: only the accused can appeal a conviction, not the state. This asymmetric right to appeal finds its rational (also) in the asymmetric epistemic positions discussed above: it is the accused and only the accused who faces the possibility of a conflict between what she knows to be true, and what has been proven in court, and she is therefore the main target of a procedure that can resolve this conflict. However, once the commission has accepted a case for review, the situation changes. Duff argues convincingly that the commission has to use its considerable investigative power to consider arguments and evidence both for and against the defendant: Duff argues, (2001 346), quoting from Home Office Discussion Paper: Criminal Appeals and the Establishment of a Criminal Cases Review Authority“ (1994) that: The Commission is not in the position of acting for the applicant nor serving his interests alone. It was intended to operate as “ a non-adversarial body conducting neutral inquiries” which should “ proceed by means of investigation rather than by conducting hearings with the parties represented”” With other words, an appeal starts within the closed system of the law, with an asymmetric procedural rule that matches the asymmetric distribution of information atypical, as we argued, for trials. It finishes however in a system much closer to the system of science, and as a result we find a symmetrical relation between defence and prosecution evidence. Excluding the parties at the Commission stage means that this process is not any longer subject to the epistemic asymmetries between them. In one examples discussed by Duff, the commission finds as part of their investigation that while an identification parade used by the police was indeed flawed, there was also another witness, not used in trial, who does confirm the guilt of the accused and whose evidence is deemed highly reliable by the Commission. In this situation, the Commission should not refer the case to the court as it does not have “a belief that a miscarriage of justice may have occurred.” Once the new Scientific Review Commission within the CCRC is established, application of the Daubert rules gives us several more, and more plausible, scenarios of this nature. An applicant may challenge the scientific validity of the scientific expertise lead against him at trial. The commission may find that while at the time of the trial, the theory in question was indeed insufficiently tested, subsequent tests confirmed its reliability to a satisfactory degree. Indeed, it is conceivable that the Commission authorises new research to settle the issue in question. In this situation, the question of the compatibility of its procedures with the trial rules of evidence would not arise, as the case would not be referred. However, it is equally possible that the Commission concludes, based on second order evidence received (say psychological expertise on the main witnesses at trial) that both prosecution and defence witnesses were highly unreliable. If the commission is convinced that the “science of witnesses analysis” meets itself the Daubert criteria, it should refer the case back to the courts, even though the court may not entertain the idea of admitting this second order evidence on procedural grounds. A particularly interesting scenario could arise regarding the concept of falsification. The commission may find that at the time of the trial, a scientific theory used as part of the prosecution evidence was still making empirical predictions that were open for testing, the theory therefore falsifiable. However, the scientists working in this area have since then reacted to negative test results by “immunising” the theory through ad hoc assumptions, exceptions and other defensive strategies which in the terminology of Lakatos turned a progressive scientific programme into a regressive one. Does this lack of empirical content now cast doubt on the reliability of a decision that was reached when the theory still had empirical content? For Popper, the answer is clear: immunising a theory in this way is an unacceptable avoidance strategy, “in reality” the theory has been falsified, the conviction is unsafe. However the Hempel part of Daubert would maintain that the positive evidence in favour of the theory (from its pre-trial testing) is as valid as ever, the theory was sufficiently confirmed at the point of application, and any changes in its structure that make it difficult to falsify now irrelevant for assessing its reliability. This point lead us directly to the issue of “temporal” asymmetries and temporal indices in scientific theories (or the lack thereof). The Commissions can take on cases any time, even after the death of the person convicted of a crime, acting in this case on behalf of surviving relatives. There are no time bars, and in principle no restrictions on the number of times that an accused may appeal to the Commission. As indicated above, there are at least no explicit reasons against the Commissions carrying out or commissioning their own tests of a disputed scientific theory, possibly in conjunction with the other extra-judicial body that will apply Daubert type criteria to assist the judiciary with the interpretation of scientific evidence, the Forensic Science Advisory Council. All this indicates that the commission operates closer to the open ended, “symmetrical” environment of scientific inquiry where it does not matter when an observation was made or a test carried out. Falsifiability of a theory now matters substantially, as it allows the Commission to probe it further. On the other hand, if the Commission has reached the decision to refer a case back to the courts, the logic of the trial reasserts itself. The judges will have to make a new “bet” on the scientific theories presented to them, by a given point in time, based now on the additional tests that have been carried out between the original verdict and the appeal hearing. Summing up, we have two “border crossings” between the systems of law and science. From a “synchronic” perspective, the appeal starts within the normative framework of the trial, with an symmetrical procedural relation that privileges the accused, but ends up within the normative structure of science, with a symmetrical relation between the parties. From a “diachronic” perspective the work of the commission takes place in an asymmetrical environment where past, present and future test of a debated theory are of equal relevance, but in communicating its finding back to the courts, the normative logic of the trial reasserts itself and reaches a decision that is purely “past oriented”: at this point in time, have sufficient tests established or undermined the forensic evidence in question? Duff, and Schiff and Nobles (2001), have analysed the CCRC from the perspective of systems theory. Their conclusions however differ. For Schiff and Nobles, the lack of an independent right of the CCRCs to overturn convictions indicates that they will remain in the normatively closed system of the law, second guessing the decisions by the Appeal Courts and hence indirectly bound by their evidentiary rules. Duff on the other hand argues that the CCRCs are bridging institutions that can at least partly transcend the conceptual limitations of the trial. With the proposed creation of a scientific committee within the CCRCs, and the suggested use of Daubert criteria by them, Duff’s reading gains considerably in plausibility. Daubert scrutiny by the Commission of trial evidence would be more rigorous than that currently applied in trials. Furthermore, the commission can also use “second order” expertise such as statistical evaluations of scientific and other evidence, which are not normally used in court as there, they would trespass into jury territory. Moreover, we argued that the Commission setting allows to resolve some of the tensions inherent in Daubert. The Daubert court tried to introduce the best available epistemological theories into a trial setting, while remaining true to the internal normative logic of the law. This inevitably created conceptual tensions when epistemological concepts were stripped of their normative contend and recast/reformulated by the recipient system. The UK set-up avoids to some extend these tensions, by operating the Daubert criteria in an environment that is free from the epistemic asymmetries that are unique to legal modes of reasoning about facts. However, it risks simply postponing the problem if the courts in turn refuse to admit the standards that used by the Commission, and only the future will tell if the courts are capable of integrating post-conviction Daubert scrutiny by the Commissions into the procedural rules governing appeals. However, as Laudan (2003) argues, rules of evidence at trial do to some extend depend on the type , quality and quantity of appeal procedures available. A legal system with particularly demanding rules of evidence at the trial stage may not need an elaborate appeal process. Conversely, he argues, the much more widely available possibilities of post conviction scrutiny in most modern legal systems also should mean a at the first instance trial, a more permissive approach to evidence can be taken. In the UK, we saw the opposite development as far as scientific evidence is concerned: A very permissive approach to admissibility will now, finally, be complemented by a much more rigorous post conviction scrutiny. The mutual interdependence between trial rules and system of appeals and post convictions scrutiny may also give a final answer to Haack’s problem with Daubert. In future, trial courts in the UK will make their decisions on the admissibility of scientific evidence in the knowledge that a much more far reaching system of post conviction scrutiny is available. The “future oriented” concept of falsifiability, apparently at odds with the with necessity “past oriented” approach to evaluating scientific theories in court, now does get a relevance of its own. A scientific theory that at the time of the trial has some, but not overwhelming, support by the academic community and been subject to some, but not extensive empirical testing may pose much less concerns for the trial judges as long as it is a theory that is falsifiable in principle – as this feature allows then the Commission to carry out proper, and “continuous”, post conviction scrutiny that takes the open ended nature of scientific enquiry into the heart of the legal system. Bibliography Allen R J., “Expertise and the Daubert Decision”, 84 Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology (1994)1157-1169 Belloni, F. and Hodgson, J. Criminal Injustice: An Evaluation of the Criminal Justice Process in Britain London: Macmillan 2000 Duff, P., “Criminal Cases Review Commissions and 'Deference' to the Courts: The Evaluation of Evidence and Evidentiary Rules”, Criminal Law Review, pp.341-362, (2001). Griffin, L "The Correction of Wrongful Convictions: A Comparative Perspective," 16 American University International Law Review 5 (2001) 1243-1308 Haack, S., “An Epistemologist in the Bramble-Bush: At the Supreme Court with Mr. Joiner”, 26 J. Health Politics, Policy and Law (2001) 217- 232 Habermas, J, Truth and Justification, Cambridge, Polity Press 2003 Kaye, D H., "On 'Falsification' and 'Falsifiability': The First Daubert Factor and the Philosophy of Science". Jurimetrics, Vol. 45 2005 pp. 473–481 Laudan, L., “Is Reasonable Doubt Reasonable?” Legal Theory (2003), 9: 295-331 Maher, P, “Probability Captures the Logic of Scientific Confirmation”. In: , Christopher Hitchcock (ed) Contemporary Debates in the Philosophy of Science) , p 69–93 London, Blackwell 2004 Nobles, R & Schiff, D., Understanding Miscarriages of Justice: Law, the Media, and the Inevitability of Crisis . Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000. O'Brian, W, “Court scrutiny of expert evidence: recent decisions highlight the tensions.” International Journal of Evidence & Proof (2003) 172-184 Roberts, P, “Towards the principled reception of expert evidence of witness credibility in criminal trials”, International Journal of Evidence & Proof (2004) 215-232 Schafer, B, “12 angry men or one good woman. Asymmetrical relations in evidentiary reasoning.” In Kaptein, Prakken and Verheij (eds), Reasoning about legal evidence, London: Ashgate 2008 (forthcoming) Schiff, David; Nobles, R. 'The Criminal Cases Review Commission: reporting success?' Modern law review 64, March (2001), pp. 280-299. Stein, A., Of Two Wrongs that Make a Right: Two Paradoxes of the Evidence Law and their Combined Economic Justification, Texas Law Review (2001)1199-1234 Taylor, N “ Post Conviction Procedures” in Walker and Starmer (eds.) Miscarriages of Justice (1999), 229 Walker, C and. Starmer K (eds) Miscarriages of Justice: A Review of Justice in Error, London: Blackstone Press (1999)