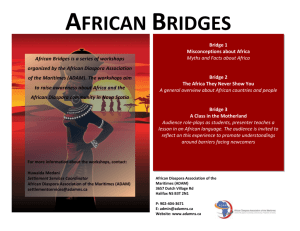

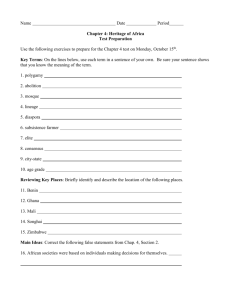

African diaspora in homeland development

advertisement