Frogs material ex Columbia University

advertisement

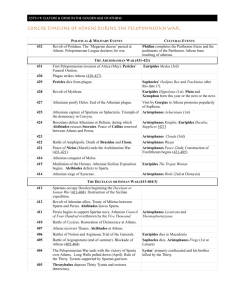

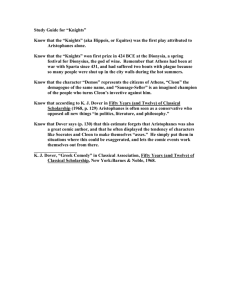

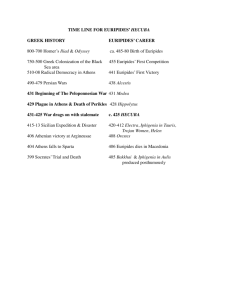

http://www.columbia.edu/~eg48/protoc16.html [ Home | Requirements | Books | Syllabus | Protocols | Further Comments | Discussion | Links | Contact ] Humanities C1001-014: Masterpieces of Western Literature and Philosophy Prof. Eileen Gillooly PROTOCOLS #13: The Frogs Written by Jessie Handbury; edited by Luis Saucedo 1. The controversy surrounding the study of The Frogs The inclusion of Aristophanes’ text in the Literature Humanities course is a highly debated topic. The pros and cons of this debate are as follows: Pros: There are too many tragedies in the course, showing only one side to Greek theatre. Aristophanes’ plays are examples of the comedic element of Greek theatre, which made up about half of what was performed. The addition of The Frogs in the course presents a more realistic and well-rounded crosssection of Greek theatre, showing that Greek society was not totally dominated by a fateful, bleak outlook on life. The study of a comedy allows for an investigation of the different dramatic techniques used in both tragic and comedic works. Though it becomes clear in studying The Frogs that the aims and potential for their fulfillment are similar in both styles of dramatic writing, the elements by which they are brought about are very different. (See below) Cons: Comedic plays are difficult to appreciate since they include many allusions and references that only a contemporary audience could appreciate. The topicality of comedy, especially Greek comedy which is intensely political, means that without an extensive knowledge of the social and political context in which a play was written, the audience is unable to fully appreciate the humor and themes of the play. In any culture comedy is based on fine word choice that can be lost in the translation. It is important to note, however, that Arrowsmith, Lattimore, and Parker have not directly translated much of the humor in the text, and have altered the language so that the intended meanings of the puns are still conveyed. Like the Cold War translation of the Peloponnesian War, the translation of The Frogs is also problematic as it is roughly fifty years old. In reading The Frogs, 1950s rhetoric and jargon need themselves to be “translated” to understand Aristophanes’ intended meaning. 2. Historical Background to The Frogs The Frogs was performed in Athens at the Lenaia Festival of 405BC. The Peloponnesian War was in its final stages. Even though Athens was defeated in 404, the writing was on the wall, so to speak, while Aristophanes was working on the play. Therefore, in order to understand the many political allusions that exist in the play, one must have a certain amount of knowledge regarding Athens’ situation in 405BC, and the events that brought it there: The “sea battle” which is referred to in Dionysos and Xanthias’ sophistic argument about the latter’s load to carry (p482) is the battle of Arginousai, fought in the summer of 406BC, just before the play was written and performed. In this battle, slaves were used to fight for Athens and then granted their freedom on victory. The battle was a success for the Athenians; however, the collateral damage was great, with around 5000 men lost. The demos was angry at this loss, and as retribution the generals, including Pericles (son of Pericles), were executed. Socrates was president of the assembly at the time and tried to keep the generals from being executed, but failed. Socrates was executed himself in 399. The “feast at Diomeia” referred to randomly on page 528, was unable to be held because the Spartans had taken over Decalaeia, a military fort. This allusion reminds the audience of the trapped position that Athens was in: they were no longer in control of their own outlying areas, the Spartans were almost at the gates of their city, and their own colonies and allies were everywhere in revolt. Aristophanes is also alluding to the danger of Alcibiades to Athens. Alcibiades was an Athenian who advised the Spartans to take Decalaeia. The danger he presented to the Athenians in situations like these came from his persuasiveness and his knowledge of the weaknesses and thought-processes of the Athenian army and its generals. Aristophanes also makes his opposition to the rule of Kleophon known throughout the play. In the final lines, the chorus calls for “Kleophon and all similar aliens” to “go home and fight”. Aristophanes did not support Kleophon’s persuasion of the demos to continue fighting, after Sparta offered them a truce following the Arginousai. 3. Elements of Old Comedy and its Power Though tragedy is often viewed as the greater power in theatre the power of comedic writing and its effects are greatly underestimated. Tragedy portrays exceptional models of humanity from whose mistakes and experiences the audience learns. It elevates society by discussing abstract principles, such as the god-like qualities of humans and the struggles of the soul. Comedy, on the other hand, is useful in conveying political ideas to the masses. Rather than elevating human figures to heroic status, comedic writing reduces humanity and even great figures to the lowest common denominator. While tragedy uses sophisticated irony and other such linguistic techniques to communicate its messages, comedy uses everyday language and humor that everybody can understand. Uneducated Greeks would not be able to understand the complicated irony of some tragedies. Tragedies might be considered as more aristocratic, and comedies as more democratic. Comedic writers can write casually, with base humor almost exclusively discussing the physical side of humanity, and have a license to state their controversial opinions though such license was limited: Aristophanes, for example, was tried for treason as a result of the slanderous political attacks he made on Cleon in his writing. Aristophanes trivializes the individuals he is making fun of by constantly including base reminders of the physical realities with which we live daily. The crudeness of the humor “breaks the ice”, and makes the subtle, ironic humor by which he conveys his opinions much more powerful. Despite problematic translations and the distance from the culture, it is remarkable how much of Aristophanes’ humor that a modern audience can relate to. The crudeness of Aristophanes’ humor is evident in: i. the “brekakakax ko-ax-ko-ax” of the frogs and Dionysos (this competition between the chorus and the god is argued to be a representation of both a singing competition and a farting contest) ii. the homosexual jokes made with reference to Dionysos (p485: his craving “for a boy”) Other conventional elements of old comedy are as follows: a journey: In this case, Dionysos goes to the underworld to bring back Euripides, satisfying a craving or pothos. This journey is traditionally to bring an inhabitant of Hades to the world to right a wrong. (N.B. the analogy between Dionysos’s craving and one for baked beans: Euripides is said to be “full of beans”.) identity and paradox: Dionysos’s identity is multiple, changing, and contradictory. The fact that he has a craving, when gods shouldn’t have pothos (craving), brings up the question of how much of a god he is. He, like Herakles, is half-man and half-god, though instead of his humanity taking precedence over his divinity as in the character of Herakles, he is worshipped as a god. In the Bacchae he defeats the expectations of what gods should be, and here his fatness (symbol of his physicality), his irrationality, and his effeminacy all make the audience question his identity. In the spirit of theatre, Dionysos is often disguised. He first disguises himself as Herakles but then switches outfits with his slave several times throughout the play so that we see him as a god and a slave repeatedly, considering that he is the god of passions to which me are often enslaved this frequent change of identity is appropriate. Dionysos’ character is performed with a mask of a smiling face which suggests mischievousness as well. Dionysos’ character fits with the topsyturvy quality and incongruity of the comedic theatre. Furthermore, his changing of identities communicates another related state of being. He is the god of wine which makes one drunk - like theatre, disguise, and passion – another state of mind: ekstasis. the agon: a contest, here between Euripides and Aeschylus, and Xanthias and Dionysos. i. Euripides’ contest with Aeschylus is a parody of The Eumenides’ trial of Orestes. The contestants use lines as evidence and present their evidence in a courtroom-like scene. ii. They contest which poet would better advise Athens in 405BC. Euripides’ plays toe fine line between tragedy and comedy: while his stories are tragic, his subjects are not leaders, he gives a voice to everyone, even the often dismissed, such as women, slaves etc. He deals with the demos and the everyday aspects of life. His mode of writing teaches the people of Athens to be critical of their leaders, and he presents the faults in their society as examples of what to avoid in the future. Like all art, comedy must educate as well as entertain. In comedy though, because the majority of it is irony and satire, the educational part of it is more easily perceived. Aeschylus, on the other hand, presents models to emulate and covers up scandal instead of illustrating it as does Euripides. The question at hand is whether to accept the fate of Athens, as Euripides would, or to be optimistic and emulate heroic models in hope of victory. Although Dionysos chooses Aeschylus to bring back to Athens from Hades it is a peculiar choice, because Aristophanes generally likes Euripides and put him in all his plays. Aristophanes’ attitude that neither poet can save Athens is suggested by the fact that no solutions are reached for the problem of Alcibiades (p577-80): Euripides echoes the parabasis in advising to rely on those leaders (ostracized for various reasons) who will do the most good for Athens, but is unsure about what to do about Alcibiades, while Aeschylus uses the example of the lion cub (relating it to Helen, who being nurtured brought destruction to Argos), to advocate relying on Alcibiades, and advises that Athens should rely on its navy, which does not exist. The argument comes out with the sense that Aristophanes’ comedy itself will save Athens, by creating distance from the situation, accepting it, and appealing to the power of poetry to help the people understand their losses. the parabasis: the part of the play where playwrights states their view clearly, Aristophanes does this through the leader of the chorus, the initiates of the Eleusinian mysteries, which in reality constituted virtually all the citizens of Athens. The parabasis shows the way in which Aristophanes feels Athens should deal with its losses, and whom to blame for them. On pages 509-10, he spells out who are to blame for the defeat, including Alcibiades as he “sells out a ship or a fort to the enemy”, and Kleophon “who gets up to speak in the public assembly and nibbles at the fees of poets”. On pages 530-1, Aristophanes again uses the leader of the Initiates to call for “amnesty” for those who supported the oligarchy camp of 411, since among these are some of the best, wisest, potential leaders of Athens. It is thought that the unusual honor of a second production of The Frogs can be attributed to the parabasis. theatricality: while tragedy needs the audience to believe that the action is real in order to be successful, comedy calls attention to its own theatricality. Anything that breaks the illusion of reality in a tragedy diminishes its effects; however, this fault in tragic theatre is a major element of comedy. Dionysos’ character involves the audience, speaking both to the audience as “criminal types” and calling to the priest in the front row. Breaking the frame bridges the distance between the audience and the dramatic action. If tragedy emphasizes the distance between the tragic hero and the audience (which is moved to fear and pity at what it witnesses), comedy emphasizes the identification of the comic characters and the audience (which should be moved to “think”, as Aristophanes says, about the similarities between their own situation and the one they witness).