Who Framed 'Social Dividend'? - The US Basic Income Guarantee

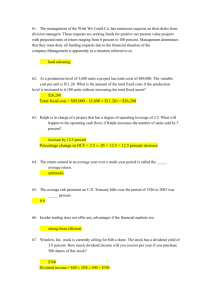

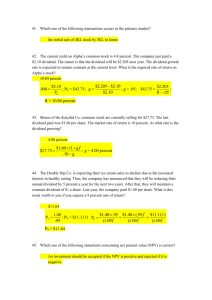

advertisement