7. IIAS working paper (Dr Kien)

advertisement

Employment Effects of Trade Expansion and Foreign Direct

Investment: The Case of Korean Manufacturing Industry1

Tran Nhuan Kien2

Abstract

Trade and foreign direct investment outflows in Korea have increased significantly

during the last two decades. In this paper, we study whether trade expansion and foreign

direct investment outflows played any role in shaping the Korean manufacturing

employment structure during 1991-2006 period. We find evidence that foreign direct

investment outflows corresponds positively to home country’s employment. In terms of

trade expansion, the role of exports and imports in employment generation has been

changed in that exports have been no longer a source a job creation while import intensity

displaced domestic jobs in recent years.

Key words: Trade, Employment, FDI, Cobb-Douglas production function, Korea

JEL Classification: F14, F15, F16

I. Introduction

Globalization is considered one of the most prominent features of the 21st-century. As

barriers to trade and investment continue to fade away, there have been an increasing

number of firms investing abroad and deepening trade relations with foreign partners.

The proliferation of globalization has sparked debates among economists and

policymakers on the effects of globalization on domestic factors such as economic

1

This paper was written while the author was Korea Foundation Fellow. The author would like to thank the

Korea Foundation for its financial support. Any errors that remain are the author’s sole responsibility.

2

Vice Dean, Faculty of Graduate Studies, Thai Nguyen University of Economics and Business

Administration, Vietnam; Email: tnkien@tueba.edu.vn; Tel. +84 976 626 611. Senior Researcher, IIAS,

Sogang University, Korea.

1

growth, poverty, inequality, and employment. With respect to labor market, evidence on

the effect of openness to trade and foreign direct investment (FDI) on employment is

mixed across countries (Hoekman and Winters, 2005; Masso etc., 2007).

Previous studies presented so far illustrates that there are no unified conclusion on the

effect of trade on employment. In a survey study, Hoekman and Winters (2005) conclude

that there are mixed evidences on the impacts of trade on sectoral employment in

developed countries, but overall the net employment effects of trade are negligible. Using

a dynamic panel data model, both Kien and Heo (2009) and Fu and Balasubramanyam

(2005) find a positive impact of export intensity on employment in Vietnam and China,

respectively. However, imports did not affect negatively Vietnam’s employment. In the

case of Australia, Gaston (1998) shows empirically a strong effect of exports on

employment while a negative impact of imports on employment is found. Greenaway,

Hine and Wright (1999) investigate the effects of trade on employment in the United

Kingdom using a dynamic panel data and conclude that trade expansion, both in terms of

imports and exports, have negative impacts on the country’s labor demand.

Regarding FDI, evidences from literatures show that no solid conclusion can be drawn

regarding the linkages between FDI and employment at both home and host countries. Fu

and Balasubramanyam (2005) find that FDI inflows bring about increased employment in

the China’s case. Onaran (2009) concludes that insignificant effects of trade and FDI

dominate in the case of central and eastern European countries with some evidence of

negative effects appears as well. In Vietnam, Jenkins (2006) however finds that that the

employment effects of FDI inflows have been minimal, or even negative. By making use

of highly disaggregated dataset, Waldkirch etc. (2009) shows a significantly positive,

though quantitatively modest impact on manufacturing employment in Mexico.

FDI outflows may have either positive or negative impacts on domestic employment.

When FDI outflows are regarded as capital flight, thus reducing domestic capital

formation, it may generate a negative impact on employment. FDI outflows may also

stimulate demand by foreign subsidiaries for domestically-produced intermediate

products (Kokko, 2006). Mariotti etc. (2003) investigate the impact of outward FDI on

the labor intensity of domestic production at firm level in the Italian case during 1985-

2

1995. They conclude that the impact is negative in the case of vertical investment in less

developed countries, and positive for horizontal and market-seeking investment in

advanced countries. Masso etc. (2007) also shows that outward FDI positively affects

home-country employment growth in Estonia. Debaere et al. (2010) investigated the

employment effect by using South Korea firm-level data. They conclude that that moving

to less-advanced countries decreases a company's employment growth rate especially in

the short run. On the other hand, moving to more-advanced countries does not

consistently affect employment growth in any significant way. Yamashita and Fukao

(2010) also find the positive employment effect of FDI outflows associated with the

Japanese MNEs overseas expansion.

This study focuses on Korea, which has embraced to globalization for a substantial period.

The country has enjoyed its high economic growth through its outward-looking policy

initiated in the early 1960s. It is interesting to note that while FDI inflows have not been

encouraged by the Korean government, FDI outflows was strongly encouraged,

especially to transfer knowledge and accumulate technological capabilities domestically

(Sachwald, 2001).

This paper focuses on two major aspects of globalization, international trade and FDI and

their impacts on manufacturing employment in Korea. This paper investigates the

impacts of trade expansion and FDI outflows on the generation of employment. The

focus of this study is on three key questions: (1) What are the impacts of trade expansion

and FDI inflows on employment in Korea? (2) How do these impacts change over time?

(3) What policy implications do these empirical results suggest?

Our contribution to the existing literature is threefold. This study incorporates both trade

and FDI into a single model. International trade and FDI are closely linked with each

other. However, the international trade and FDI have been separated in the analysis of

employment effects in the existing literature. Second, this study uses a system GMM

estimator, which is more appropriate for a short panel dataset than the static or first

differenced GMM estimator. The rest of the paper is organized as follows. Section II

specifies the model of trade and ODI’s impacts on employment in Korea and methods of

estimation of these impacts. Section III discusses the empirical results. The final section

3

brings forward conclusions.

II. Model Specification and Estimation Methods

Based on the Cobb-Douglas production function, this paper investigates the impact of

trade expansion and FDI on employment in the manufacturing sector in Korea using a

system GMM estimator. The Cobb-Douglas production function shows physical output as

a function of labor and capital inputs, that is:

Qit A Kit Nit

(1)

where:

i denotes industry

t denotes time

Q represents real output

A represents total factor productivity (TFP).

K represents capital stock

N represents units of labor utilized

and denote factor share coefficients

allows for growth in efficiency in the production process

Assuming that firms are profit-maximizing, the marginal productivity of labor equals the

wage (w) and the marginal revenue product of capital equals its real cost (C). Solving this

system simultaneously to eliminate capital from the expression for firms' output yields

the following equation:

Nit Wi

Qit A

* Nit

C

(2)

Taking logarithms to linearize and rearrange the equation (2) provides the derivation of

the firms', and thus the industry’s, derived demand for labor as:

ln N it 0 1 ln(

Wi

) 2 ln Qit it

C

(3)

where 0 ( ln A ln ln ) ; 1

; 2 1

and it is a disturbance

( )

( )

( )

term.

Regarding the total factor productivity (TFP), A, one may expect that TFP of the

4

production process increases over time and that the rate of technology adoption and the

increases in x-efficiency would be correlated with trade expansion and FDI inflows via

pressures of competition in the international markets and knowledge spillovers from FDIfunded imports and other foreign contacts. In fact, previous empirical studies (Fu and

Balasubramanyam, 2005; Hoekman and Winters, 2005; Greenaway et al., 1999; Lawrence,

2000; Liu and Wang, 2003; Savvides and Zachariadis, 2005) show that exports, imports,

and FDI inflows all have impacts on the TFP. On the one hand, existing studies focusing

on the role of exports and imports as sources of the impacts on TFP conclude that both

exports and imports, by and large, enhance productivity (Hoekman and Winters, 2005;

Greenaway et al., 1999; Lawrence, 2000). Regarding the impacts of FDI on TFP,

empirical evidences indicate the positive effect of FDI on TFP (Fu and Balasubramanyam,

2005; Liu and Wang, 2003; Savvides and Zachariadis, 2005). This can be partly explained

by the fact that the FDI inflows is not only a source of capital, but also a supplier of

technology transfer. Therefore, parameter A is hypothesized in the production function,

which varies with time in the following manner:

Ait e 0Ti X it1 M it 2 FDI it3 ,

0 , 1 , 2 , 3 0

(4)

Where,

T is time trend

X is export intensity index of industry i in year t (measured by export-output ratio)

M is import penetration index of industry i in year t {measured as a share of apparent

consumption (is measured as domestic production + imports – exports)}.

FDI is the inflows of foreign direct investment of industry i in year t.

Therefore, the labor demand equation can be derived from the combination of (3) and (4)

as follows:

ln N it 0* 0T 1 ln M it 2 ln X it 3 ln FDI it 1 ln(

Where, 0*

Wi

) 2 ln Qit it (5)

C

(ln ln )

;

; 0 0 ; 1 1 ; 2 2 ; and 3 3

( )

( )

Many economic relationships are dynamic, and one of the advantages of panel data is that

they allow researchers to understand the dynamics of adjustment (Baltagi, 2001). Thus, a

substantial number of studies have dealt with dynamic effects; for example, Holtz-Eakin

5

(1988) on a dynamic wage equation, and Arellano and Bond (1991) and Greenaway et al.

(1999) on a dynamic employment model. These dynamic relationships are characterized

by the presence of lagged employment among regressors. To take adjustment processes

into account, time lags are also introduced for the independent variables.

t

t

t

j 1

j 0

j o

ln Nit i 0T 0 j ln Ni ,t j 1 j ln X i ,t j 2 j ln M i ,t j

t

j o

3j

t

Wi ,t j

j 0

Ct j

ln FDI i ,t j 1 j ln(

t

(6)

) 2 j ln Qi ,t j t it

j 0

where i is unobserved industry-specific effects; t is time-specific effects.

Following Greenaway et al. (1999) and Milner and Wright (1998), variation in users' cost

of capital (c) is captured by time dummies in estimation by assuming perfect capital

markets; thus it varies only over time. Explanatory variables are assumed to have

common impacts across industries.

In order to eliminate the industry specific effects and to ensure that the two-year lag of

level variables is not correlated with error terms, the employment equation (6) is

differenced and a dynamic employment equation is derived as follows.

t

t

t

ln Nit 0 0 j ln Ni ,t j 1 j ln X i ,t j 2 j ln M i ,t j

j 1

j 0

t

t

Wi ,t j

j o

j 0

Ct j

3 j ln FDI i ,t j 1 j ln(

j o

t

) 2 j ln Qi ,t j t it

(7)

j 0

indicates differences in variables’ transformation; for example,

ln N it ln N it ln N i ,t 1 . Unlike the unobserved industry-specific effects, time-specific

where

effects are not eliminated by the difference transformation of variables.

However, the differenced equation (7) creates another problem (namely endogeneity)

because it is clear that ΔlnNi,t-1 and Δεi,t-1 are correlated, thus makes OLS, fixed effects,

random effects, and feasible generalized least squares (FGLS) techniques yield biased

and inconsistent estimates (Baltagi, 2001; Harris & Mátyás, 2004; Nickell, 1981;

Sevestre & Trognon, 1985). It would therefore be inappropriate to estimate equation (7)

by these techniques.

To deal with this problem, the most favorable approaches to date which could give

6

unbiased and consistent results are IV and GMM estimators. However, this study uses a

GMM estimator for two reasons. First, if heteroskedasticity is present, the GMM

estimator is more efficient than the simple IV estimator; whereas if heteroskedasticity is

not present, the GMM estimator is no worse asymptotically than the IV estimator (Baum

et al., 2003). Second, the use of the IV method leads to consistent, but not necessarily

efficient, estimates of the model's parameters because it does not use all available

moment conditions and it does not take into account the differenced structure on the

residual disturbances (Baltagi, 2001, p. 130).

The GMM estimators, which include first-differenced GMM (DIF-GMM) developed by

Arellano and Bond (1991), and system GMM (SYS-GMM) developed by Blundell and

Bond (1998), are increasingly popular for estimating dynamic panel datasets. As

pointed out by Blundell and Bond (1998) and Bond et al. (2001), however, the DIFGMM estimator has been found to have poor finite sample properties, in terms of bias

and imprecision, when lagged levels of the series are only weakly correlated with

subsequent first-differences. They also show that DIF-GMM may be subject to a large

downward finite-sample bias, particular when the number of time periods available is

small. The SYS-GMM estimator thus is more appropriate than DIF-GMM for our

model. Therefore, a SYS-GMM estimator will be employed as the main method to

estimate the employment equation in this study. In this paper, GMM estimated

coefficients are based on the one-step GMM estimator, with standard errors that are not

only asymptotically robust to heteroskedasticity but have also been found to be more

reliable for finite sample inference (see Blundell and Bond, 1998)3.

We estimate the model based on a panel dataset on manufacturing sector corresponding to

the two-digit International Standard Industrial Classification level. The dataset were

collected from the following sources. Data on industry exports and imports were

extracted from the United Nations Statistics Division Commodity Trade Statistics

Database (UN COMTRADE). Data on wages and output were extracted from the Korean

Statistical Information Service (KOSIS). The original source of these data was from the

Mining and Manufacturing Survey which is conducted annually covering all firms with

five or more employees in mining and manufacturing industries. The survey adopted the

new classification from 2007. Therefore, the dataset used for regression cover the period

of 1991-2006. However, the year 1998 is considered as an outliner as Korea’s economy

was deeply affected by the Asian financial crisis. Hence, 1998 data were excluded from

3

In finite samples, the asymptotic standard errors in the two-step GMM estimators can be seriously biased

downwards and thus give an unreliable guide for inference (Bond etc., 2001).

7

the regression. To obtain the real wages and real output, these data were deflated by

industrial producer price index which was also from the KOSIS. Finally, ODI data was

obtained from the Overseas Direct Investment Statistics Yearbook (published by The

Export-Import Bank of Korea).

III. Estimation Results and Discussions

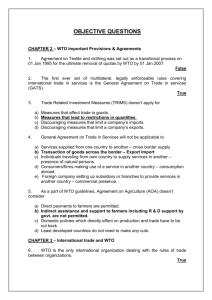

Tables 1 to 3 report the results of one-step GMM estimations of Equation (7) for Korea.

The estimations are made first for the full sample dataset, and then for two separate subperiods, that are the period before the Asian financial crisis from 1991-1997 and the

period after the crisis from 1999-2006. The purpose is to capture possible changes in the

effect of trade and ODI on employment in manufacturing sector after the financial crisis.

In our GMM estimation, we treat all the regressors as endogenous variables.

Table 1. Korea’s System one-step GMM Estimation Results: Full Sample

Independent Variables

ln Nt-1

ln (W/C)t

ln (W/C)t-1

ln Qt

ln Qt-1

ln EXTENt

ln EXTENt-1

ln IMPENt

ln IMPENt

ln ODIt

ln ODIt-1

Constant

AR (1) p-value

AR (2) p-value

Instrument validity test (Sargan)

No. of groups

Total observations

Specification 1

(Base model)

Coefficient

t-ratio

0.2228

4.11***

-0.2484

-2.80 **

-0.0732

-1.28

0.2934

4.71 ***

0.0752

2.71 **

-0.0116

-3.41***

0.017

0.847

0.19

22

286

Specification 2

(Full model)

Coefficient

t-ratio

0.183

4.13***

-0.274

-2.63**

-0.072

-1.61

0.346

4.34***

0.096

3.26***

0.019

1.53

0.014

1.69

0.003

0.12

-0.005

-0.25

0.006

2.04*

0.005

2.36**

-0.013

-3.59***

0.024

0.355

0.19

22

286

Note: 1. The dependent variable is ln Nt

2. Coefficients on time dummies are not reported

3. ***, **, and * represent statistical significance at the 1%, 5%, and 10% level, respectively.

Table 1 reports the regression results for full sample data of 1991-2006 period. The

Sargan test of overidentifying restrictions and Arellona-Bond second order

autocorrelation test are presented at the end of the table. The Sargan test of over-

8

identifying restrictions can not reject the validity of the instrumental variables. In

addition, the Arellona-Bond test shows the evidence of first order autocorrelation, which

is expected, but no evidence of second order autocorrelation.

In the first part of Table 1, estimated coefficients of our base specification where both

output and wage have the expected impacts. It shows that growth in current output

positively impacts employment at 1% significant level; whereas growth in current wage

has a negative effect on employment at 5% significant level. While the impact of wage

fades away, the impact of output is still strong and robust. The estimated coefficient of

the lagged dependent variable is positive and statistically significant, indicating the

persistence both the wage and output effects on the level of employment.

In the second part of Table 1, both trade and ODI were introduced into the model. The

expected sign and significant level of lagged dependent variable, wage, and output are

still the same as in the base model, indicating the robustness of the model. The results of

second order autocorrelation and instrumental validity indicate that the model performs

well with no second order autocorrelation and no correlation between the instrument set

and the residuals. According to the results of this specification, we can not find any

statistical significant relationship between exports and employment as well as imports

and employment. However, outward direct investment corresponds positively to home

country’s employment. This result is consistent with the results of Lipsey etc. (2000) for

the case of Japan and Masso etc. (2007) for Estonia. Lipsey etc. (2000) justified that the

supervisory and ancillary employment at home to support foreign operations outweighs

any allocation of labor-intensive production to developing countries. This fact also can be

attributed to the demand stimulation by foreign subsidiaries for domestically-produced

intermediate products.

Table 2. Korea’s System one-step GMM Estimation Results: 1991-1997

Independent Variables

ln Nt-1

ln (W/C)t

ln (W/C)t-1

ln Qt

ln Qt-1

ln EXTENt

ln EXTENt-1

ln IMPENt

ln IMPENt

ln ODIt

Specification 1

(Base model)

Coefficient

t-ratio

0.381

0.003

0.077

0.041

0.243

4.18***

0.01

0.47

0.24

3.41***

Specification 2

(Full model)

Coefficient

t-ratio

0.245

-0.071

-0.001

0.141

0.374

0.037

0.034

-0.037

0.023

0.011

2.59**

-0.31

-0.01

0.71

5.78***

1.69

2.22**

-0.68

0.63

1.98*

9

ln ODIt-1

Constant

AR (1) p-value

AR (2) p-value

Instrument validity test (Sargan)

No. of groups

Total observation

0.008

-0.021

-0.08

0.051

0.850

0.09

22

110

1.03

-0.127

-0.49

0.064

0.785

0.26

22

110

Note: 1. The dependent variable is ln Nt

2. Coefficients on time dummies are not reported

3. ***, **, and * represent statistical significance at the 1%, 5%, and 10% level, respectively.

Table 2 presents the result of estimations for the sub-period of 1991-1997. However, the

impact of wage on employment is not statistically significant. It is essential to highlight

in this period that exports are positively correlated with employment whereas imports do

not have statistically significant impacts on employment. It is argued that the major bulks

of manufacturing imports were machinery and transport equipments (accounted for

around 35 percent of total imports in the 1990s, Table 3), which were highly intraindustry trade. Thus, imports were a complementary to domestic productions thus it did

not necessarily have negative impacts on employment. Regarding ODI, current

investment outflows are positively correlated with employment at 10 percent significant

level. However, lagged investment outflows are positive but statistically insignificant,

indicating that the positive impact is weak in this period and that the positive impact

fades away.

Table 3. Korea’s System one-step GMM Estimation Results: 1999-2006

Independent Variables

ln Nt-1

ln (W/C)t

ln (W/C)t-1

ln Qt

ln Qt-1

ln EXTENt

ln EXTENt-1

ln IMPENt

ln IMPENt

ln ODIt

ln ODIt-1

Constant

AR (1) p-value

Specification 1

Specification 2

(Base model)

(Full model)

Coefficient

t-ratio

Coefficient

t-ratio

0.151

1.28

0.150

1.44

-0.383

-8.33***

-0.265

-5.52***

-0.086

-1.13

-0.146

-1.96*

0.437

10.13***

0.496

10.08***

0.041

0.61

-0.015

-0.21

0.017

0.99

0.005

0.39

0.033

1.26

-0.079

-2.41**

0.014

3.18***

0.004

1.39

-0.159

-3.67***

-0.174

-4.40***

0.002

0.002

10

AR (2) p-value

Instrument validity test (Sargan)

No. of groups

Total observation

Note: 1. The dependent variable is ln Nt

0.631

0.08

22

132

0.862

0.194

22

132

2. Coefficients on time dummies are not reported

3. ***, **, and * represent statistical significance at the 1%, 5%, and 10% level, respectively.

The estimated coefficients for the post crisis period are reported in Table 3. As compared

to the first period, wage and output behave better in terms of statistical significance. Also,

the magnitude of the impacts is stronger. It is noteworthy to witness the changes in the

effects of exports and imports on employment. Exports are no longer positively correlated

with employment at the conventional level of significance. On the other hand, imports

have negative impacts on employment in this period. This means that the growth of

imports is negatively associated with the employment, indicating that import intensity

will displace domestic job. This result is consistent with the study of Heo and Park (2008),

which shows that import penetration in Korean manufacturing has positively impacted

the job displacement rate. Concerning ODI, we find a positive impact of investment

outflows on employment at a 1% statistical significance. The positive employment effect

of ODI was stronger in this period as compared to the previous period owning to the

deepening of the market-seeking investment.

IV. Conclusion

This study analyzes the impacts of trade expansion and outward direct investment on

employment in the case of Korea. The study yields several notable results. It shows that

growth in current output positively impacts employment; whereas growth in current wage

has a negative effect on employment. The impacts of output have been found to be

stronger in compared to wage on employment. Outward direct investment corresponds

positively to employment which can be explained in a number of ways such as the

supervisory and ancillary employment at home and the demand stimulation by foreign

subsidiaries for domestically-produced intermediate products. The role of exports and

imports in employment generation has been changed in that exports have been no longer

a source a job creation while import intensity displaced domestic jobs in recent years.

11

REFERENCES

Arellano, Manuel, and Stephen R. Bond. 1991. “Some Tests of Specification for Panel

Data: Monte Carlo Evidence and an Application to Employment Equations.” The

Review of Economic Studies 58, no. 2: 277-97.

Baltagi, H. Badi. 2001. Econometric Analysis of Panel Data (2nd ed.). New York: John Wiley

and Sons.

Bond, Stephen R., Anke Hoeffler, and Jonathan Temple. 2001. “GMM Estimation of

Empirical Growth Models.” CEPR Discussion Paper no. 3048. London: Center for

Economic Policy Research.

Baum, Christopher F., Mark E. Schaffer, and Steven Stillman. 2003. “Instrumental

Variables and GMM: Estimation and Testing.” Boston College Working Paper No.

545. Chestnut Hill: Boston College.

Blundell, Richard, and Stephen R. Bond. 1998. “Initial Conditions and Moment

Restrictions in Dynamic Panel Data Models.” Journal of Econometrics, 87, no. 1:

115-43.

Debaere, Peter, Hongshik Lee, and Joonhyung Lee. 2010. “It matters where you go:

Outward foreign direct investment and multinational employment growth at home”.

Journal of Development Economics 91, no.2: 301 – 309. Export-Import Bank of

Korea (2010), Overseas Direct Investment Statistics Yearbook, Seoul

Fu, Xiaolan, and VN Balasubramanyam. 2005. “Exports, Foreign Direct Investment and

Employment: The Case of China.” The World Economy 28, no. 4: 607–25.

Gaston, Noel. 1998. “The Impact of International Trade and Protection on Australian

Manufacturing Employment.” Australian Economic Papers 27, no. 2: 119-36.

Greenaway, David, Wyn Morgan, and Peter Wright. 1997. “Trade Liberalization and

Growth in Developing Countries: Some New Evidence.” World Development 25,

no. 11: 1885–92.

Greenaway, David, Robert Hine, and Peter Wright. 1999. “An Empirical Assessment of the

Impact of Trade on Employment in the United Kingdom.” European Journal of

Political Economy 15, no. 2: 485–500.

12

Hoekman, Bernard M., Aaditya Mattoo, and Philip English. 2002. Development, Trade

and the WTO: A Handbook. Washington, D.C.: World Bank.

Hoekman, Bernard, and L. Alan Winters. 2005. “Trade and Employment: Stylized Facts

and Research Findings.” World Bank Policy Research Paper 3676. Washington,

D.C.: World Bank.

Heo, Yoon, and Miri Park. 2008. “Import Competition and Job Displacement: A Case

Study of Korean Manufacturing Industries.” Social Science Journal 45, no. 1:

182–93.

Jenkins, Rhys. 2006. “Globalization, FDI and employment in Viet Nam.” Transnational

Corporations 15, no. 1: 115-42.

KOSIS. 2010. Statistical Database, Korean Statistical Information Service. Available at:

http://www.kosis.kr/eng/

Kokko, A. 2006. “The Home Country Effects of FDI in Developed Economies.” EIJS

Working Paper No. 225, The European Institute of Japanese Studies.

Kien, Tran Nhuan, and Yoon Heo. 2009. “Impacts of Trade Liberalization on Employment

in Vietnam: A System Generalized Method of Moments Estimation.” The

Developing Economies 47, no. 1: 81–103.

Lawrence, Robert. 2000. “Does a Kick in the Pants Get You Going or Does It Just Hurt?”

in Robert Feenstra, ed. The Impact of International Trade on Wages. Chicago:

University of Chicago Press, pp. 197-224.

Liu, Xiaohui, and Chenggang Wang. 2003. "Does foreign direct investment facilitate

technological progress? Evidence from Chinese industries." Research Policy 32, no.

6: 945–53.

Litchfield, Julie, Neil McCulloch, and Alan Winters. 2003. “Agricultural Trade

Liberalization and Poverty Dynamics in Three Developing Countries.” American

Journal of Agricultural Economics 85, no.5: 1285–91.

Lipsey, Robert E., E. Ramstetter, and M. Blomström. 2000. “Outward FDI and Parent

Exports and Employment: Japan, the United States, and Sweden.” Global

Economic Quarterly 1, no. 4: 285-302.

Masso, J., U. Varblane and P. Vahter. 2007. “The effect of Outward Foreign Direct

Investment on Home-Country Employment in a Low-Cost Transition Economy.”

Eastern European Economics 46, no. 6: 25-59.

Milner Chris, and Peter Wright. 1998. “Modelling Labour Market Adjustment to Trade

Liberalization in an Industrializing Economy.” The Economic Journal 108, no.

13

447: 509-28.

Mariotti, S.; M. Mutinelli; and L. Piscitello. 2003. “Home Country Employment and

Foreign Direct Investment: Evidence from the Italian Case.” Cambridge Journal of

Economics 27, no. 3: 419–31.

Menil, Georges. 1997. “Trade Policies in Transition Economies : A Comparison of

European and Asian Experiences.” in Wing Thye Woo, Stephen Parker and Jeffrey

D. Sachs (eds.), Economies in Transition: Comparing Asia and Eastern Europe,

Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press.

Nickell, J. Stephen. 1981. “Biases in Dynamic Models with Fixed Effects.” Econometrica 49,

no. 6: 1417-26.

Onaran, Ozlem. 2009. The effect of trade and FDI on employment in Central and Eastern

European countries: a country-specific panel data analysis for the manufacturing

industry. In: Tondi, Gabrielle, (ed.) The EU and emerging markets. European

Community Studies Association of Austria (ECSA Austria). Springer.

Sachwald, F. (2001) ‘Globalization and Korea’s Development Trajectory: the Role of

Domestic and Foreign Internationals’, in Sachwald F. (ed). Going Multinational:

The Korean Experience of Direct Investment, London: Routledge.

Savvides, Andreas, and Marios Zachariadis. 2005. “International Technology Diffusion

and the Growth of TFP in the Manufacturing Sector of Developing Economies.”

Review of Development Economics 9, no. 4: 482-501.

Sevestre, Patrick, and Alain Trognon. 1985. “A Note on Autoregressive Error Component

Models.” Journal of Econometrics 28, no. 2: 231-45.

Shin, M., H. Mirza, and K.N. Kim. 2009. “Foreign Direct Investment by the Republic of

Korea in the People’s Republic of China.” Asian Development Review 26, no. 2:

102–24.

United Nations Conference on Trade and Development. 2009. “Trade Analysis and

Information System (TRAINS).” http://r0.unctad.org/ trains_new/index.shtm

(accessed March 09, 2009).

United Nations Statistics Division. 2009a. “United Nations Commodity Trade Statistics

Database.” http://comtrade.un.org/db/default.aspx (accessed March 15, 2009).

Waldkirch, A., P. Nunnenkamp and J. E. A. Bremont, 2009, Employment Effects of FDI

in Mexico’s Non-Maquiladora Manufacturing, Journal of Development Studies 45,

no. 7: 1165-83.

Yamashita, N. and K. Fukao. 2010. “Expansion Abroad and Jobs at Home: Evidence

from Japanese Multinational Enterprises.” Japan and the World Economy 22, no.

14

2: 88-97.

*This research project was carried out by the support of the Korea Foundation under the

academic guidance of Professor Yoon HEO at Sogang GSIS.

15