Becoming Vocational: insights from two different vocational courses

advertisement

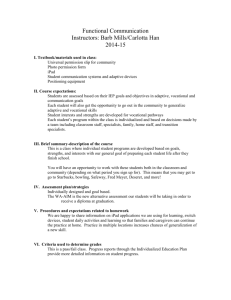

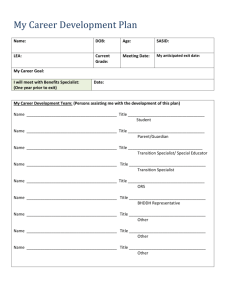

EX_JD_MT_PUB_CONF_09.03.doc Becoming Vocational: insights from two different vocational courses in a further education college A report from the project Transforming Learning Cultures in Further Education by Jennie Davies and Michael Tedder presented at the British Educational Research Association Conference, Edinburgh, September 2003 Jennie Davies School of Education and Lifelong Learning University of Exeter Heavitree Road Exeter EX1 2LU Tel: 01392 264787 E-mail: Jenifer.M.Davies@exeter.ac.uk Michael Tedder St Austell College Trevarthian Road St Austell Cornwall PL26 7YE Tel: 01726 226736 E-mail: mtedder@st-austell.ac.uk Becoming Vocational: BERA 2003 Becoming Vocational: insights from two different vocational courses in a further education college by Jennie Davies (University of Exeter) and Michael Tedder (St Austell College) Abstract The paper is based on work undertaken for the project Transforming Learning Cultures in Further Education which forms part of the Economic and Social Research Council’s Teaching and Learning Research Programme. It draws on ongoing longitudinal case studies of two learning sites in the project, both Level 3 two-year vocational courses in the same further education college. It illuminates the nature of the formation and transformation of young people’s vocational aspirations in these sites – a BTEC National Diploma in Health Studies, and an Advanced Vocational Certificate in Education in Travel and Tourism. Initial impressions of two strongly contrasted sites regarding students’ vocational aspirations are compared with the more complex picture of similarities that emerges. Specific attention is given to the nature of the relationship between students’ learning on these courses and their shifting vocational aspirations. Issues of identity formation and the role and status of vocational courses for young people are raised, with implications for FE policy and practice. Introduction The Transforming Learning Cultures in Further Education (TLC)1 project involves close working partnerships between researchers based in universities and in further education colleges and includes a teacher from each of the learning sites 2, the participating tutor. Together they explore the recent learning experiences of tutors and students, so that the project can ‘examine learning processes, dispositions and cultures over time and in relation to a wide range of personal experiences and other factors’ (Bloomer & James, 2003). Our data are drawn from two learning sites at a further education (FE) college in the south west of England: a BTEC National Diploma in Health Studies and an Advanced Vocational Certificate (AVCE) in Travel and Tourism. Our case studies (Davies, 2003; Tedder, 2003) 1 2 For more information on the project visit the website (www.ex.ac.uk/education/tlc). In TLC the term ‘learning site’ is used rather than ‘course’, to denote more than classroom learning; it encompasses the entire time and space within which learning takes place. 2 Becoming Vocational: BERA 2003 focus on data derived from the first cohort of students during the academic years 2001/02 and 2002/03. We have conducted in-depth semi-structured interviews with a sample of students towards the beginning and at the end of each year of their course. Other data that inform this study derive from repeated interviews with the participating tutor in each learning site, entries from their reflective journals, researcher observations and a questionnaire survey administered to all students in the learning site at the start of each academic year and at the end of their course. The paper begins by describing the research context and then focuses on the shifting vocational aspirations of students in our two sites, with a short student case study from each. The case studies were not chosen as a conventionally representative sample, but for the insights they provide into the relationships between students’ learning, their vocational aspirations and their developing identities. The ensuing discussion draws out similarities between the two sites which have implications both for those teaching and managing vocational courses in FE and for policy makers. Context Our findings here have links with other research into young people’s lives, in particular with research that focuses on the formation of identities and on the decisions young people make as they move from education into employment. Our findings show how students’ vocational aspirations are inextricably bound up with other aspects of their lives, with issues of identity, with becoming a person. It is acknowledged that young people today are growing up in a world characterised by rapid change, increased complexities and uncertainties (Beck, 1992; Furlong and Cartmel, 1997). This is a world where many of the old certainties have gone, where lives are multidimensional (Dwyer and Wyn, 2001) and where adulthood is often deferred (the ‘post-adolescence’ described by Wyn and Dwyer, 1999). It is a world which includes an unprecedentedly wide range of possibilities in employment and further and higher 3 Becoming Vocational: BERA 2003 education, a range which can appear to individuals at its extremes as either bewildering or incomprehensible. Giddens (1991) claimed that, for the ‘reflexive project of the self’: Modernity confronts the individual with a complex diversity of choices and… at the same time offers little help as to which options should be selected (p 80). We are interested in the way young people confront such diversity and try to select options. The recognition of ‘choice biographies’ (du Bois Reymond, 1998) does not imply a discounting of long-standing structural constraints like class, gender and ethnicity on many young people’s choices. As Furlong and Cartmel (1997) have explained: Young people can struggle to establish adult identities and maintain coherent biographies, they may develop strategies to overcome various obstacles, but their life chances remain highly structured, with social class and gender being crucial to an understanding of experiences in a range of life contexts (p109). Frequently, however, these constraints are unrecognised: ‘The young people see themselves as individuals in a meritocratic setting, not as classed or gendered members of an unequal society’ (Ball et al 2000). As part of the discourse on the transition from school to work, Hodkinson and Sparkes (1997) put forward the theory of ‘careership’, which discounts both structural determinism and individual agency alone. This theory provides a more complex awareness of career decisions than the traditional concept of career trajectory with its inherent emphasis on the feasibility of technically rational decision-making. As they explain: In this theory, three artificially-separated parts are completely inter-related. They are pragmatically rational decision-making, choices as interactions within a field, and choices within a life course consisting of inter-linked routines and turningpoints. We coined the term ‘careership’ as a shorthand title for the whole (p32). 4 Becoming Vocational: BERA 2003 Indeed, young people will always make their career decisions within ‘horizons for action’: ‘By horizon for action we mean the arena within which actions can be taken and decisions made’ (Hodkinson and Sparkes, 1997, p34). Such ideas help to make sense of the unfolding stories of our students during a different time of transition, from school to a vocational course in college. The complexities of the relationships between young people’s decisions about their education and other aspects of their lives have been explored in a number of recent longitudinal studies (for example, Ball et al, 2000; Bloomer and Hodkinson, 1997, 1999; Dwyer and Wyn, 2001). The concept of ‘learning career’ (Bloomer, 1997; Bloomer and Hodkinson, 2000) is helpful in understanding some of these complexities. Bloomer (1997) challenges the assumption that learning careers are susceptible to prediction and rational planning: Learning careers describe transformations in habitus, dispositions and studentship, over time. They cannot be planned in any technical or rational sense; they happen or ‘unfold’. Their futures are unpredictable to the extent that there is much that is unpredictable about the conditions under which unfoldment or happenstance takes place (p 153). This paper focuses on students’ learning careers in two specific vocational courses and explores the relationship between those learning careers and the students’ vocational aspirations and decision-making. From our interview data we can provide an account of the ways in which the learning careers of some vocational students are ‘unfolding’. The learning sites Our initial impression of the two learning sites, which are both Level 3 two-year courses - BTEC National Diploma in Health Studies (HS) and AVCE in Travel and Tourism (TT) - was one of superficial similarities but an essential difference. Of the similarities, one was the overwhelmingly female nature of both groups (there was just one TT male student and none in HS). In addition, all students were aged 16 or17 at the start of their course, apart from one TT student aged 25. They looked 5 Becoming Vocational: BERA 2003 similar in that they dressed in conventional rather than conspicuous youth fashion, and sported no visible tattoos or flamboyant piercings. Of the less visible aspects, all had met the entry requirements of their course (4 subjects at grade C or above for the AVCE and the BTEC, with the option also of BTEC First Diploma award for the HS course). The majority in both TT and HS had gained nine or ten GCSE passes with at least a grade C. Another similarity was the fact that they all had either already acquired part-time jobs by the start of their course in 2001 or else acquired them soon afterwards, and for many the number of hours at work increased considerably during our two years’ relationship with them. This aspect of their lives was to prove increasingly significant in relation to their studies, as we discuss later. The main difference seemed to concern vocational aspirations. At the start of the autumn term 2001, most HS students were aiming for a career in the health service, the majority wanting to be nurses and aware that this would involve an HE course after their BTEC. One student had her sights set on HE, but not on a specifically health-related course. Perhaps as a result of this reasonably strong vocational bonding, the classroom dynamics of this group initially appeared to be more cohesive than those in TT. The TT students, in contrast, appeared to be bound together more by a shared commitment not to go to university than by any firm vocational aspirations to work in TT. Such aspirations as they expressed appeared to be vague, sometimes founded on ideas of cabin crew or overseas representatives gained from the media or holidays abroad, sometimes simply on a general wish to travel. Sometimes they were avowedly non-existent. Subsequent interview sweeps, however, revealed a more complex picture of aspiration-setting in both HS and TT, with more profound similarities rather than differences emerging as significant. Travel and Tourism AVCE TT, a ‘Vocational A-level’, has been available at the College since September 2000, replacing the GNVQ Leisure and Tourism Advanced qualification. Course knowledge consists of 12 discrete units (6 compulsory and 6 chosen by our participating tutor from a list of options) and is assessed two-thirds by assignments, and one third by external examinations. TT students can also take optional additional 6 Becoming Vocational: BERA 2003 subjects, many with clear vocational relevance. There is, however, no work experience included in the AVCE. The following table maps the vocational aspirations during the two years of their course of each of the seven students who were being interviewed in 2002/03, two of the original sample having left at the end of the first year. It maps both changes and the consideration of options, as well as some apparently consistent aspirations. But such a table can present only the bald outline of each student’s developing vocational aspirations and identities. It is followed by a short case study tracing the changes expressed by Hayley Abbott which fills in some of the rich detail that lies beneath and between her shifting aspirations. 7 Becoming Vocational: BERA 2003 Table 1: Changing vocational aspirations - AVCE Travel & Tourism interviewees Pseudonym 1st interview 2nd interview 3rd interview 4th interview Hayley Abbott Redcoat at Butlins HE Foundation Degree: marketing (market research executive) Year out, possibly in Greece; maybe television work Ground crew at nearby city airport Becky Carr Administrator, possibly abroad Long-term goal: house renovation business HE Degree: public Possibly degree, Temporary work relations but not public in USA visiting relations; not TT father; not TT career career HE Foundation Degree: tourism management; marketing via her job at local tourist attraction Events organiser; possibly HE Foundation Degree - subject not decided Children’s rep, but keeping options open Children’s rep; hotel management Year out, then possibly HE Foundation Degree Cabin crew Not yet interviewee Modern apprenticeship (construction); cabin crew; overseas rep; outdoor activities instructor Not yet interviewee Applying for HE Foundation Degree in events management; not necessarily aiming at TT career Any local job; later - overseas rep or cabin crew Not yet interviewee Not yet interviewee Tamsin Ellis Overseas rep; hotel work Lindsay Fletcher Events organiser, not necessarily in TT Dennis Giddings Not yet interviewee but in 2nd interview said he had had no goal at this stage Helen Newman Carol Nichols Camp America next summer; work in local tourist office Travel agency work; airport work; HE Foundation Degree: tourism management Any local job; possibly with tourist board in future Hotel management; work-based NVQ at local hotel (where she works); HE Foundation Degree: leisure and tourism management 8 Becoming Vocational: BERA 2003 Hayley Abbott - ‘It depends on what you want out of life really.’ Hayley, a confident and articulate young woman, had left school a year before starting the AVCE TT, with 9 GCSEs (4 B grades and 5 C grades). After leaving school, she started AS courses at the College ( Sociology, Psychology, English, Drama, Politics and General Studies) but left when she developed glandular fever. She had decided against returning to A-levels because she was adamant she did not want to go to university and she seemed to have drifted into the AVCE TT before deciding that it might lead to a possible career for her. Her choice did not appear to be based on any substantial decision-making process; it seemed more the product of happenstance. Her interest in tourism was apparently triggered by working as a waitress in a local hotel, when recovering from glandular fever: So, I mean to begin with I was thinking of going back to do the A-levels but once I found I had an interest, I thought it might be a better avenue to go down. (1st interview, Nov 2001) With a long-standing interest in drama she also confessed, ‘I wanted to be a Redcoat at Butlins and I still kind of do, and this is of course another avenue into going into it.' By her second interview in May 2002, there was evidence of a clearer goal, although not one necessarily focused around travel and tourism. With an interest awakened by the marketing unit on the course, she was considering a two-year foundation degree in marketing, in order to become a market research executive, and the earlier idea of becoming a Redcoat had now vanished. The vocational insights from her third interview in November 2002 could be summarised in her own words, repeated several times, ‘I keep just having different ideas’. She spoke at length about possible future plans, which no longer included a career in marketing. Other aspects of her life now appeared to be more influential, like the desire to move away from the locality and to have some time apart from her long-term boyfriend (‘I need to do stuff before I settle down properly anyway’) and she appeared to be toying with several new ideas, namely going to work in Greece or trying to enter the world of television. 9 Becoming Vocational: BERA 2003 Hayley was now formulating a desire for an interesting job with a reasonable salary away from her home village. She stressed the value of qualifications for her generation: Well there's not really much you can do [without qualifications]. I mean I've got friends who left school and didn’t go to college and they're like chambermaiding and waitressing which is fine - you know they wanted to do that. But I wouldn’t want to be barmaiding in the pub for the rest of my life or anything, so it depends what you want out of life really. (3rd interview, Nov 2002) She valued the AVCE TT, but not for specific vocational reasons; Hayley’s emphasis was on its generic qualities: ‘It leads, you know, it doesn’t just lead to jobs in travel and tourism…. I'm getting lots more skills that can be used outside of the scope of travel and tourism’. However, by the fourth interview in May 2003, Hayley’s vocational focus had moved from the general to the particular, and she now sounded firmly focused on a specific career in the travel industry: I’m applying for jobs at the moment. I’ve applied at [the local] airport as a passenger service rep…I’ve also applied for a temporary position at [a regional] airport as a customer service rep and I’ve also sent my CV to Britannia, Air 2000 and My Travel…I want to start off on a like a check-in desk and then, hopefully, move up to like an airport controller… [it’s] probably the first step in the career. Her part-time job appeared to have been the most influential factor in these latest decisions, as it had helped her develop confidence in customer service: ‘I like working with the general public and … I know how to deal with like awkward customers and stuff like that, which you do get at airports’. This job had also contributed towards crystallising her priority, to earn a decent wage soon; she had spent enough time ‘doing the menial jobs that don’t pay very well and stuff like that’. So her earlier passing vocational aspirations, including the possible university course, had all now disappeared, because 10 Becoming Vocational: BERA 2003 [I am] fed up with being broke, I think. I just want to get a job where I can earn. There’s no age limit on doing your education, so if I find I’m not getting anywhere in work, then [I’ll] think about it [HE] then, when I’ve got some money behind me to go and do it. I’ve got so many friends at uni now that are struggling because they haven’t got any money and are having to get jobs as night barmaids, or whatever, to support their uni funds, and it’s just putting them behind in their work and I don’t want to end up like that, so. It’s a lot of money for something that you’re not putting your best into. The most recent twist to her story, from information that emerged a few weeks after this fourth interview, is that her boyfriend was moving to the city near the regional airport she had applied to, and her priority was now to join him and find work there. Domestic aspirations expressed in the first two interviews, when she hoped to be ‘settling down’ and having children by the age of about 23, were, however, not mentioned again. She was not thinking about the future beyond the next year: Until I find out what I’m going to be doing, I don’t think I really can think that far ahead. I want to take some time out and travel in a few years, but not now. Again, it’s something I don’t want to do without money. (4th interview, May 2003) It seems that Hayley’s changing vocational aspirations during her course are part of other, wider personal changes - in particular, in her relationship with her longstanding boyfriend and in her attitude towards moving away from her home area. They could be described as ‘exploratory’ rather than fixed in any way, with the possibility of continuing into HE surfacing and resurfacing throughout the two years despite her initial rejection of university. When considering both university and other employment possibilities, her phrasing was markedly tentative: ‘I wouldn’t mind’, ‘I’m not positive’, ‘I’m just thinking about it’. Her course appears to have been influential in the development of her own ‘choice biography’ in three ways: by widening her horizons for action, by encouraging her to think of having a career rather than simply a job, and by giving her skills not limited to the field of travel and tourism. We cannot, of course, assume that these influences will automatically endure once she leaves college. 11 Becoming Vocational: BERA 2003 From her academic profile and articulate responses in class, Hayley’s tutor expected her to achieve high grades for her assignments, but this expectation was largely unfulfilled. How influential was Hayley’s own lack of vocational focus together with the weak vocational bonding of the group here? How significant were structural factors, like her increasing lack of time for study because of the demands of her job? Whether, if she had set herself more focused vocational goals, she would have aimed for higher grades it is impossible to gauge, as she had made it clear in the first interview that for her, having a balance in life was essential: ‘I know you shouldn’t put work first, but you know everyone has other things they need to do’. She had also stressed the need to relax: 'I don't like to wear myself down too much, I mean I take evenings off'. Her learning career did not change as significantly as her tutor had expected and we might conjecture that this was due to a combination of shifting vocational and personal aspirations. Her story indicates how throughout her course she was combining decisions regarding work, personal matters and learning, as du Bois Reymond (1998) describes. Using the terminology of ‘careership’ referred to previously, we see her making ‘pragmatically rational decisions’ throughout the two years; we see her making choices ‘as interactions within a field’; and by the fourth interview, ‘choices within a life course consisting of inter-linked routines and turning-points’. At the time of her last interview, it was clear that structural issues and personal needs were paramount rather than a clear-cut vocational goal. Health Studies Within the College the BTEC ND Health Studies course is one of a cluster of three in the Care area, the other courses being BTEC Social Care and BTEC Early Years. The course has 18 modules in a ‘core plus options’ model and has a strong science focus when compared with the other care courses. Students are expected to undertake 400 hours of work placement, gaining experience in three areas of care: with children, with the elderly and with people who have special needs. The interviews have elicited the shifting, malleable nature of student ideas about 12 Becoming Vocational: BERA 2003 possible careers arising from the interaction of, among other factors, their course experiences, work placements and part-time work commitments. Table 2 illustrates briefly the changing aspirations of the six interviewed students over the two years of their course. Of these six who were recruited for a course perceived by many as a preparation for nursing, four actually started the course with that specific career intention and two finished it with that intention. The table is followed by a short case study of one of the interviewed students, Rachel Norris. 13 Becoming Vocational: BERA 2003 Table 2: Changing vocational aspirations – BTEC Health Studies interviewees Carol Gardner 1st interview 2nd interview 3rd interview 4th interview Degree to study Criminal Justice or Psychology Not interviewed Forensic science; Interests in paramedic – police – lab assistant Foundation Degree in Human Bioscience Possibly mental health nursing ‘eventually’ Army to do degree Judy Goodall Paramedic Paramedic Unsure about paramedic – possibly police Police or Ambulance Technician Rachel Norris Carer for people with special needs HE: nursing diploma Paramedic Paramedic HE: nursing diploma Nurse first then Midwife HE locally to train as nurse ‘Going off nursing’ Interest in Radiotherapy ‘Permanent student’ Anti-nursing Perhaps local HE Foundation Degree Bridget Robson Sandy Spencer Nurse first then Midwife Possibly nurse for the elderly HE locally to train as nurse then USA and possibly midwife training in Australia HE locally or within the region for nursing. Not sure about midwife Paramedic interest ‘Dream job’become a midwife, work in the private hospital in London ‘that does the celebrity babies’ Lynne Turner Children’s nurse HE within the region for children’s nurse training HE within the region for Diploma or Degree in children’s nursing + intensive care HE Advanced Dip in children’s nursing. Intensive care. Possible specialisation in nursing children with disabilities Psychiatric nurse 14 Becoming Vocational: BERA 2003 Rachel Norris - ‘They kind of expect you to know already what you’re doing.’ Rachel achieved 11 GCSE subjects at grade C or above from school. She lives in a village a few miles from the College with her father and a brother. Her family are generally supportive of her educational aspirations but it seems that, despite her relative youth, there were quite strong pressures on her to make a decision about a career direction: They’re just really glad I’ve made up my mind what I want to do … My nan was getting fed up because one day I wanted to be a lawyer, one day I wanted to be a graphic designer then I wanted to be in the police force then I wanted to be in the RAF and she got quite fed up with it. I’ve settled down now. (1st interview, Dec 2001) In fact, Rachel originally applied to the College for the BTEC ND in Social Care but there were too few students for that course to run and she settled for Health Studies. She sees herself as a ‘practical’ person and the appeal of nursing for her was partly the variety of practical work it entails. While there was no substantial history of health or care work in her family, Rachel has close relatives who have learning difficulties and she showed an unusually strong ideological commitment to this field of work, a disposition which presumably arises from that family experience: I always think to myself I always want to work with adults with special needs because, when children like that are young it’s like “oh, poor little children” but when they’re older they’re like pushed back out of society. I think that’s wrong. I think a lot more people need to think the way I do - that they are people and need to be cared for. (1st interview, Dec 2001) Coming to college gave Rachel aspirations to go to university. In the early weeks of the course she found out about the NHS bursary and this allayed some of the financial anxieties she shares with many youngsters, particularly those in working class and rural areas, about undertaking higher education. By the second interview, she had developed plans for work and study abroad. Rachel was the only one of the six interviewed students who did not have part-time employment at the start of the course but as a result of a work placement in the spring term at a residential care home she was offered – and accepted – a job as a care assistant. At the second interview she said that she worked between six and 24 15 Becoming Vocational: BERA 2003 hours per week and that, on occasions, worked as many as 30 hours. What she valued about the placement was ‘doing something really, really helpful’ and working as part of a team. Rachel had become a temporary member of a community of practice (Lave and Wenger, 1991) and showed increasing vocational confidence within that community: All the senior carers told me I was doing really well and they’re extremely impressed with me. I like knowing that I can do it right and that I am doing it properly. (2nd interview, June 2002) In our discussion of her work Rachel was able to talk about a growing sense of professional awareness, recognising the trust placed in her by relatives of the residents. She was able to articulate the dilemma of reconciling her feelings about the residents with the expectation of professional detachment: You find it’s a lot different to people who work in other jobs. You’re more attached to your work because it’s actual people you’re caring for. They say you don’t get too close to them, you shouldn’t really, cause it’s a professional relationship but you do get attached to some people. (2nd interview, June 2002) However, at the third interview, towards the end of the first term of the second year, a significant shift had occurred in Rachel’s plans. It emerged that she had been working as many as 50 hours per week in the residential care home where she had started as a ‘part-time’ employee. The home was short staffed, and Rachel was a willing and effective worker who had become increasingly vital to the functioning of the home. Eventually, this commitment had taken its toll on her health and on her participation in the Health Studies course: she had been absent frequently and was falling behind with coursework. Her willingness to write coursework assignments had changed markedly. Asked why she had taken on so many hours of work she talked of the financial benefits, of the social gains and independence made possible from being able to run a car. Rachel’s career aspirations had changed significantly also: she no longer wanted to be a nurse but instead planned to become a paramedic, an idea she said had come 16 Becoming Vocational: BERA 2003 partly from hearing a talk by a visiting speaker and partly from contact with a friend who is an ambulance care assistant. It was at the third meeting that Rachel expressed the view that talks about careers should come in the first year. She said, ‘They kind of expect you to know already what you’re doing, if you know what I mean, where you’re going and what you want to do’. (3rd interview, Dec 2002) By the fourth interview, near the end of the course, Rachel was disengaging from the residential home and planning to widen her experience in other fields of care. She spoke of plans to work for an NVQ3 qualification and of applying in time for paramedic training. She mentioned a recently validated degree course she had come across for paramedics but no longer had plans to go to university, even though her closest friends from the course were due to leave in the autumn for universitybased training. Her plans for travel and study had been shelved and she no longer considered the possibility of nursing: No, I wouldn’t want to be a nurse, now, not at all! ….I just – I don’t know. A nursing job seems to be so stressful. They’re short-staffed etc and I wouldn’t want to do it at all. It’s not very nice. (4th interview, June 2003) Over the two years we can start to trace the unfolding of Rachel’s learning career within her horizons for action. What we see is someone who started her course with a positive disposition to learning and an open attitude to vocational possibilities. She had enjoyed academic success at school and achieved high qualifications, suggesting she had a wide scope for possible careers. She showed distinct values about ‘caring’ derived from her experiences with family members. Rachel was pragmatically rational in considering her actions but had to reconcile a number of conflicting influences within the decisions she made. She has a general commitment to members of the community in need of care and that commitment rendered her particularly well suited to the care home where she secured part-time employment. Becoming a significant worker within the field of ‘care’ consequently became a powerful possible identity. At the same time, Rachel is a young person with the social interests common for her age group, so she aspired to financial independence and the perceived freedom of 17 Becoming Vocational: BERA 2003 action that such independence may offer. This was likely to reinforce the attraction of employment over study. Encounters with others who could describe the job of a paramedic – a visiting speaker, a colleague in the care home – presented another possible vocational identity, one that had the potential to provide financial independence sooner than nursing and one that was also compatible with a family preference for Rachel not to leave the area. The cumulative effect is that Rachel arrived at a turning point half way through the second year of her course, a turning point that rendered problematic her continued work with the BTEC course. In the early part of the course, work placements appeared to provide a powerful formative experience for several of our interviewed students. Our interviews have recorded how they make connections between the course and their own lives, interpreting their experiences at work sometimes by reference to course content and frequently by reference to relatives. There are risks with work placements, however, and Rachel illustrates one of them, that a capable student may become absorbed into the workplace, almost certainly prematurely. Discussion Despite some initial apparent differences in students’ vocational aspiration-setting between TT and HS, as the two courses progressed, more similarities emerged. In both learning sites, some students began to consider HE as the next step and in both the majority were now considering employment in their specific field. It would appear that both learning sites influenced their students, but in at times subtle and, to the tutors, unexpected ways. Firstly, there were not necessarily links between prior high academic achievement or high academic achievement on the course and students’ more focused vocational goals. On the AVCE, the two students who showed most determination to achieve high grades were two of those who joined the course without TT vocational goals: Becky and Helen. Over the two years, their TT goals had not shifted radically, yet they were the students with the highest grade profile overall. Two HS students who 18 Becoming Vocational: BERA 2003 had weak academic records – Carol and Judy – were on target to achieve the BTEC Diploma at the end of the course; Carol had rather undefined vocational aspirations while Judy had well defined ideas. Moreover, there were concerns that other students with a more accomplished academic record would not achieve the award. Within these two sites, therefore, there seemed little correlation between having welldefined vocational goals and eventual achievement of the award. What seems significant is that the links between students’ learning and their vocational aspirations form an integral part of students’ on-going identity formation. It is apparent from all of their stories that the processes of vocational identity formation and aspiration-setting are bound up in those of wider identity formation. These students are at a time in their lives when they are becoming more independent and when they are taking on more adult roles. Their identities are continually transforming in a variety of subtle ways and they are sometimes conscious of these changes and sometimes not. A strong theme emerging from our research is that vocational orientation is one important aspect of identity formation, but that it is an integral part, inextricably linked with other aspects of young people’s lives. Secondly, the interviews reveal some important insights into the dispositions to learning and knowledge of these young people. Bloomer (1997) characterised dispositions as stable but capable of changing perceptibly or imperceptibly from time to time and from one situation to the next: Changes in dispositions, and hence studentship, were profoundly influenced by both in-course and out-of-course experiences. In-course experiences of learning frequently prompted students to reappraise themselves as learners (and exceptionally as persons) and to revise the values they ascribed to particular forms of knowledge or types of learning activity (p 138). The BTEC and AVCE learning sites both encompass significant vocationally-related elements beyond the activities of many conventional college courses: HS requires students to complete 400 hours of work placement, while TT offers students the opportunity to achieve various industry-based certificates (BTEC Intermediate Certificate Preparation for Air Cabin Crew Service, Overseas Resort Representatives 19 Becoming Vocational: BERA 2003 BTEC Certificate, Air Ticketing, and Association of British Travel Agents’ Certificate). These elements comprised powerful experiences for students that impacted on their dispositions and studentship. Such powerful experiences need sensitive handling by tutors. It is superficially attractive to have ‘work placement’ as an element of any course that claims to be ‘vocational’ but evidence from the HS course suggests that careful preparation and support are necessary if such experience is to be effectively integrated with other elements. Tutors may need to give as much consideration to the likely emotional and ethical demands as to the cognitive demands of work placements. In both learning sites we found that shifting career aspirations were associated with shifting attitudes towards higher education. Initial shifts tended to favour courses in local higher education institutions, but as some students became more committed to continuing their studies they could describe detailed career plans, often involving travel for study and work abroad. Again, there are important issues to be explored about appropriate tutor and college support during such changes of vocational aspiration. The third significant aspect of the relationship between these learning sites and the construction of students’ vocational aspirations is the effect of students’ part-time jobs on their studies. Part-time employment played an increasingly significant role in all our students’ lives over the two years of their courses. All students found parttime jobs during the first year of their course, and the majority increased their hours so that by the second year some were working regularly as many as 30 hours a week. At the start of the second year, only three of the seven TT interviewees described themselves as predominantly ‘student’; two described themselves as ‘worker’; and two more as ‘in-between’, with equal student/worker identities. By the end of the second year, the majority of these students considered they had this shared identity rather than a mainly student identity. We could postulate that encouraging a stronger ‘student identity’ might lead to a more positive influence on studying. The spiral of earning and spending seemed to hold an increasingly seductive appeal for our students. The interviewed students from both sites were still living with a 20 Becoming Vocational: BERA 2003 family member, and the majority were in receipt of an educational maintenance allowance (EMA), but they still wanted or needed to earn their own spending money. Students aspired to have an income, in order to furnish a lifestyle that included clubbing, drinking, and the possession of fashionable clothes, a mobile phone and a car. For many in this rural area, learning to drive and running a car is a particular priority. The HS tutor commented how car availability resulted in some students attending only when there were formal course activities. The nature of the course experience thus changed subtly and, for the students, imperceptibly. Many students also talked about how much they enjoyed their jobs which they saw as their ‘social life’, and ‘fun’. Bloomer (1997) noted that, for many young people, personal growth and development were outside school or college: a world which afforded new friendships, new social activities, new knowledge and new questions…. Indeed, the ‘other world’ proved to provide many rich and challenging experiences from which students truly learned and which gave shape to and was shaped by, their emergent personal identities (p 139). Most students came from families who, in Bourdieu’s terms, hold limited cultural capital (Bourdieu, 1984) where parents had not continued into further or higher education themselves. Some, but by no means all, also came from families with limited economic status. Many showed an awareness of being the first not to participate in a culture of working rather than studying at sixteen. Thus there appeared to be various pressures on these young people to earn alongside studying and they found it increasingly difficult to resist offers of longer hours from their employers. Needs and wants became intermingled for them, and the rigours of pursuing Level 3 courses in comparison became less attractive for many as time went by. The prevalence of these attitudes presents an ongoing challenge to tutors. What are the most appropriate ways of managing students’ learning, when they appear unwilling or unable to prioritise their course? Students’ horizons for action appear to be influenced in ways that to them are barely perceptible but to tutors are only too plain. 21 Becoming Vocational: BERA 2003 Conclusion We need to emphasise that this paper reports work in progress; we have another year of data collection for the project including a final, fifth interview with our TT and HS students planned to take place about six months after completing the course. It is possible, even probable, that individuals’ vocational aspirations will have shifted again by then. Our student stories do not tell us about direct causal links between studying a Level 3 vocational course and formulating vocational goals. Instead, they tell us about the interrelationship between young people’s developing identities and their vocational aspirations, between their learning careers and their careership. We would argue that the interrelationship is far more complex than policymakers would appear to recognise. In 14-19: opportunity and excellence (2002) vocational choice is presented as a straightforward and unproblematic task: An effective 14-19 phase will depend on young people receiving effective advice and guidance so that they can make the best choices and manage their options well (DfES, 2002, vol 1: p36). Our students’ awareness of their vocational possibilities changed during their vocational courses but we saw little evidence of their having ‘longer-term learning and career aspirations’ (DfES, 2002, vol 2: 27). There was far more evidence of short- or medium-term thinking about learning and careers and that has significant consequences and implications for FE colleges. A further point concerns the way courses like TT and HS are marketed and presented to students. The picture we gained from interviewing students was of schools promoting the A-level route, of either non-existent or superficial careers advice, and of welcoming but opaque vocational options in FE. Students told us that they expect vocational courses to be ‘practical’ and many had difficulties with the level and extent of written work required. Neither of our courses equipped students for specific employment in their fields, unlike another learning site in TLC, the CACHE3 course which provides vocational training for nursery nurses. To progress 3 Council for Awards in Childcare and Education 22 Becoming Vocational: BERA 2003 to a career in either TT or HS would usually require further qualifications (for example to work as cabin crew or paramedic), and sometimes this would be via a university course (in, for example, tourism development or nursing). Indeed both TT and HS include as much ‘job invisibility’ as ‘visibility’ (Foskett, N. and HemsleyBrown, J., 2001, p186), some of which is made visible to them through their tutors during their course. Another implication concerns the status of different courses within colleges. Both of our learning sites lead to A-level equivalent qualifications yet neither course is included within the College’s Sixth Form Centre which is exclusively for the ‘goldstandard’ single A-level subjects, available at AS and A2. Moreover, both of our tutors felt that their courses were valued less highly by many colleagues within the College than ‘academic’ courses. The long-standing divide between vocational and academic appears to be as entrenched as ever. Finally, our research findings emphasise that the TT and HS courses may introduce students to specific vocational paths but equally can help them to develop more generic skills that might lead them to consider other directions. Yet young people were not aware of this when deciding which FE course to take on leaving school. ‘An holistic lifestyle view of careers’ (Foskett, N. and Hemsley-Brown, J., 2001, p187) accords with our students’ stories; the latter point to the value of keeping options open rather than an over-emphasis on a narrower vocational view. There are subsequent further implications for colleges, both in the way courses are conducted in particular with how exploratory and open they can be - and in colleges’ responsibilities to students over the transition from FE to work. It could be that more open discussion of students’ experiences of ‘vocational’ courses throughout their learning careers might enable future FE students to make more informed choices. As with the term ‘academic’, the nuances of the term ‘vocational’ are wide-ranging and need to be made transparent to would-be learners. Acknowledgement Transforming Learning Cultures in Further Education is part of the ESRC Teaching Learning Research Programme, Project No. L 139 25 1025. 23 Becoming Vocational: BERA 2003 References Ball, S.J., Maguire, M., & Macrae, S. (2000) Choice, Pathways and Transitions Post16, London: RoutledgeFalmer. Beck, U. (1992) Risk society: Towards a new modernity, London: Sage. Bloomer, M. (1997) Curriculum Making in Post-16 Education - the Social Conditions of Studentship, London: Routledge. Bloomer, M. and Hodkinson, P. (1999) College Life: the voice of the learner, London: Further Education Development Agency. Bloomer, M. and Hodkinson, P. (2000) ‘Learning Careers: continuity and change in young people’s dispositions to learning’ in British Educational Research Journal, 26, 5. Bloomer, M. & James, D. (2003) ‘Educational Research in Educational Practice’ Journal of Further & Higher Education 27,3, pp 247-256. Bois-Reymond, M. du (1998) ‘I don’t want to commit myself yet: Young people’s life concepts’ in Journal of Youth Studies, 1,1, pp 63-79. Bourdieu, P. (1984) Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste, London: Routledge. Davies, J. (2003) AVCE in Travel and Tourism Travel and Tourism Case Study, TLCFE Project Working Paper. DfES (2002) 14-19: opportunity and excellence, Annesley: DfES Publications. Dwyer & Wyn, (2001) Youth, Education and Risk:Facing the future, London: RoutledgeFalmer. Foskett, N. & Hemsley-Brown, J. (2001) Choosing Futures: Young People’s DecisionMaking in Education, Training and Careers Markets, London: RoutledgeFalmer. Furlong, A. and Cartmel, F. (1997) Young People and Social Change: individualization and risk in late modernity, Buckingham: Open University Press. Giddens, A. (1991) Modernity and Self-Identity: Self and Society in the Late Modern Age, Cambridge: Polity Press. Gleeson, D. (2001) ‘Transforming learning cultures in further education’ in College Researcher 4, 3, p3-32. 24 Becoming Vocational: BERA 2003 Hodkinson, P. and Sparkes, A. (1997) ‘Careership: a sociological theory of career decision making’ in British Journal of Sociology of Education, 18, 1. Lave, J. & Wenger, E. (1991) Situated Learning: Legitimate Peripheral Participation, Cambridge University Press. Tedder, M. (2003) BTEC National Diploma in Health Studies Case Study, TLCFE Project Working Paper. Wyn, J. and Dwyer, P. (1999) ‘New Directions in Research on Youth in Transition’ in Journal of Youth Studies, 2,1, p5-21. 25