Geert Hofstede™ Cultural Dimensions

advertisement

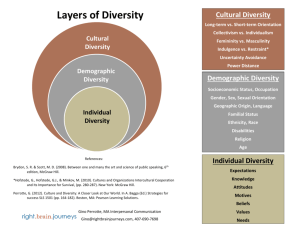

Evaluation Paper 1 of 13 Evaluation Paper Sizemore’s Cross-Cultural Communication Model By Elizabeth Sizemore Submitted in Partial fulfillment Of the Requirement for LDR 630 Organization Culture and Communication Siena Heights University Battle Creek, Michigan March 1, 2007 Evaluation Paper 2 of 13 Table of Contents Geert Hofstede™ Cultural Dimensions …………………………………………………….... 3 Shannon-Weaver Model ……………………………………………………………………… 5 Sizemore’s Cross Cultural Communication Model …………………………………………. 7 Cultural Bubble Analysis …………………………………………………………….. 8 In Action ……………………………………………………………………………… 11 Evaluation Paper 3 of 13 Evaluation Project By combining the research of Geert Hofstede with the communication model of Shannon and Weaver, a third model, Sizemore’s Cross-Cultural Communication Model, compares the similarities and differences between the cultures of individuals involved in business transactions and then factors that information into their methods of communication. Geert Hofstede™ Cultural Dimensions . The model above represents the work of Geert Hofstede who analyzed patterns of behavior in various countries. The majority of the information used in his study was obtained through access to an IBM database containing the scored results of employee value assessments. IBM’s information covered a period of six years and encompassed over 70 countries. (Hofstede 2003) The results of Hofstede’s initial study lead to the formation of four Cultural Dimensions: Power Distance Index (PDI), Individualism (IDV), Masculinity (MAS), and Uncertainty Avoidance Index (UAI). In an additional investigation, the fifth Cultural Dimension, Long-Term Orientation (LTO), was applied to 23 of the original countries. The additional Dimension resulted from a survey of students using a tool invented by Chinese scholars relating to “Virtue Evaluation Paper 4 of 13 regardless of Truth.” (Hofstede 2003) Today, the Five Cultural Dimensions cover 74 countries. Explanations are listed below: Five Cultural Dimensions 1. Power Distance Index (PDI): PDI relates to the distribution of power between members of an organization (or family) and to the level in which those members accept that distribution. 2. Individualism (IDV): Opposite of collectivism, IDV relates to the relationship between an individual and the group. This does not include the type of government in a country, but to the level individuals are responsible for and linked to their relatives and other group members. Individualistic societies maintain loose ties – being responsible for themselves and their immediate family. Collectivist societies establish close ties within their group – being responsible for an extended family throughout life. 3. Masculinity (MAS): MAS compares the difference and levels between the male and female role in the society. 4. Uncertainty Avoidance Index (UAI): UAI illustrates how a culture responds to the unknown or different. The countries who score low on UAI establish stricter laws, security measures, and religious practices. Higher scoring countries have fewer laws, more tolerant levels of religion, and an increased openness for personal ideas and actions. 5. Long-Term Orientation (LTO): Indicates the values a country places on tradition and long-term commitments. High LTO shows a philosophy of work hard today and efforts will be paid off in the long run. (Slow and steady is the course.) Conversely, low LTO shows the potential for rapid change due to fewer commitments to tradition. (International Business Center 2007) Evaluation Paper 5 of 13 Shannon-Weaver Model Information Source Transmitter Receiver Destination Received Signal Signal Message Message Noise Source Often presented to students as their first look into the process of human communication, this model was first developed by Claude Elwood Shannon in 1948. In history, this was about thirty years into the use of mass radio and at the introduction of the television era. (Griffin 1997) Working as a research scientist at Bell Telephone Company, Shannon designed his “mathematical theory of signal transmission” for use with telephone lines. Later, the theory was expanded by Warren Weaver in the book, The Mathematical Theory of Communication, to cover all interpersonal communication. (Wikipedia 2006) Today the model receives criticism connected to its linear representation of complex communication and to its overall simplicity. However, it originally gained popularity because for the first time, an uncomplicated model represented the communication process. Evaluation Paper 6 of 13 Listed below, Chandler (2005) explained the details of each part of Shannon-Weaver’s Model of Communication. 1. Source: Refers to who or what produced the message – often an individual. 2. Message: The information being sent by the source and received by the destination. 3. Transmitter: the device that encodes the message into signals. 4. Signal: The coded information traveling through a channel. 5. Channel: The means by which the signal is carried – for example, air, light, paper, electricity, radio waves, or the postal system. 6. Receiver: This decodes the message into a useable form for the source. Two examples include the human ear or the television set. 7. Destination: The location where the message arrives – often an individual. 8. Noise: Anything that distorts, interrupts, or distracts from a clear signal. The original theory focused primarily on technical noise – physical noise that disrupts the channel. Examples include: a fuzzy television screen; a chainsaw running when you’re talking to the person holding it; the cell phone signal “breaking up”; or water on a magazine page that runs the ink together. However, over time the model expanded to also include semantic noise – distraction that takes focus away from the message. For example, imagine a student attempting to read the assigned text and their significant other turns on the student’s favorite TV show. Soon the student’s attention splits and he/she can’t remember much of the chapter that was just read. Additionally, a second type of semantic noise results from difference in the use of the code. For example, the information source speaks Chinese but the destination only understands Spanish. The breakdown of communication did not result from any technical problem. The message simply was not understood. Evaluation Paper 7 of 13 Sizemore’s Cross Cultural Communication Model Message Channel Message Information Destination Source Cultural Bubble Culture of Information Source Culture of Destination The information source refers to the person(s) who generate the message. Message The message is the intended information being sent to the destination. The destination receives the information sent by the source Channel Cultural Bubble The channel conveys the information. Examples include sound waves, e-mail, telephone, paper etc. Inside the cultural bubble, all the components of culture (customs, assumptions, language etc.) from all parties involved mix and interact. The outer edge of the bubble has a thick wall that is difficult to penetrate. Attempts at communication must break through this barrier, or it will bounce-off and end up in miscommunication. Miscommunication occurs when the information sent by the source is not received by the destination with its intended meaning Culture of Information Source Culture of Destination By understanding the Culture of the Information Source, the source can identify areas in his/her own thought and behavior that possibly could be misunderstood or offensive to the destination. The Culture of the Destination can be researched before-hand in an attempt to understand and prevent errors in communication. Evaluation Paper 8 of 13 Cultural Bubble Analysis The following illustrates the intended use of Sizemore’s Cross-Cultural Communication Model. In the example, preparation for a meeting between Japanese and American business associates involves participants researching the culture of each country. This information can be found on-line, in books, and trade magazines. The specific information presented for this analysis was taken from the 2003 Geert Hofstede web-site and from the workbook, Shoulder to Shoulder: Working Effectively with the Japanese, compiled by Ellen L. Koga and distributed in 2005 by DENSO International America, Inc. Cultural of Japan using the Hofstede Analysis • • • • • Masculinity is the highest characteristic – showing a high degree of gender differentiation UAI shows a collectivist culture that avoids risks and shows little value for personal freedom A high LTO indicates a society that places significance on tradition and supports a strong work ethic PDI score shows that inequality and class systems exists in its society Lowest ranking factor is Individualism showing close ties with families and group members Evaluation Paper 9 of 13 Cultural of USA using the Hofstede Analysis • Highest ranking, IND, demonstrates a concentration on self, the immediate family, and only loose bonds with others. • The second highest ranking was Masculinity. This shows that males control the majority of the power in society. However, the current trend supports women moving into male roles and away from traditional female roles. • PDI level shows a tendency towards equality between government organizations, class levels, and within families. • UAI shows that the USA tends to set fewer laws, allows the individual the freedom to speak out, to pursue success, to quest for personal happiness, and to practice one’s own religious believes. • LTO placed as the lowest Dimension. This correlates with a culture which is flexible to quick change and puts less emphasis on tradition. Evaluation Paper 10 of 13 Analysis: Shoulder to Shoulder: Working Effectively with the Japanese Power Distance Index JAPANESE CULTURE AMERICAN CULTURE Agree to agree Agree to disagree How did you arrive at that? Job well done! Neo-Confucianism: everyone has their place and is treated accordingly Everyone is treated equal and entitled to equal treatment Person's status determines your behavior We all put our pants on one leg at a time Only boss is treated with respect Boss and subordinate should treat each other with respect Since children are used to negative feedback, young associates can handle the same kind of treatment from their bosses. (You idiot!) Since children may not be used to constant negative feedback from parents, they may not be emotionally prepared if their first boss treats them this way Individualism JAPANESE CULTURE AMERICAN CULTURE Don't bring shame upon the family Family Meeting - Junior can cast the deciding vote Here's what my group thinks Here's what I think Main source of identity comes from work - their primary group allegiance Main source of identity can come from individual interest like family and hobbies Don't be arrogant Show that pride We'll all have steak Make mine low carb and on the side Masculinity JAPANESE CULTURE AMERICAN CULTURE Male dominated society History of a male dominated society Women slowly moving into more power Large trend towards women in power positions Evaluation Paper 11 of 13 Uncertainty Avoidance Index JAPANESE CULTURE AMERICAN CULTURE Only one way to write company reports As long as its professional How you say or do something is as important as the result The ends justify the means Disagreement = Confrontation U.S. created by loudly opinionated founding fathers Long-Term Orientation JAPANESE CULTURE AMERICAN CULTURE Language - verbs and negatives come at the end. Allows you to save face. Get to the point. Cut to the chase. Lay your cards on the table Nonverbal communication style: "Say one thing, understand ten" Explicit communication style: "Say twenty things, understand ten" Negative feedback is given publicly and loudly Negative feedback is given privately and calmly The associate feels secure that even if he is yelled at, he will always have a job at the company Constant criticism makes the associate wonder about his future at the company Singling someone out for public praise may make him/her feel awkward Publicly praising someone boost his/her morale Cross-cultural Communication Model in Action After the associates complete preparation to understand the culture of individuals involved in an upcoming bi-cultural businesses meeting, the American facilitator should then takes steps to “penetrate the wall of the cultural bubble” and (hopefully) prevent miscommunication. To begin, distribute background material before the meeting. In Japan, the reason for a meeting is only to share the decisions already made through Nemawashi, pre- Evaluation Paper 12 of 13 meeting discussions. However, an American might think, “No agenda was distributed in advance. I’ll just guess what this meeting will cover.” In addition, Japanese tend to shy away from public confrontation. They will agree to agree even when they disagree. Sending out the meeting’s agenda allows them time to discuss areas of disagreement beforehand. Subsequently, encourage participants to speak their native language when brainstorming, allowing time for participants to formulate thoughts. Brainstorming is a common American practice, however, a Japanese associate might think, “A meeting that is brainstorming has no value. I am just here to figure out what they couldn’t figure out on their own.” In addition, frequently summarize the meeting’s progress to avoid misunderstanding caused by the language barrier. Finally, watch for body language. In Japan, individuals often do not like to say no. Remember, they will often say yes even if they do not agree. Furthermore, they apply a non-verbal communication style in contrast to the explicative style utilized in the United States. Therefore, check for non-verbal clues to the true meaning of the message sent. In conclusion, blindly entering into any form of information sharing between bi-cultural parties might easily enter into misunderstanding. Participants need to take the time to research not only the laws but the culture of projected business associates. Ideas taken for granted in one culture, such as no bribes in the United States, may possibly be quite different in another, i.e. gifts are expected in Japan. To aid in research, numerous tools are available from various sources. One of the most recognized, Geert Hofstede Cultural Dimensions for International Business is easily available on the Internet. Fused with the research of Shannon and Weaver, these two models combine to form Sizemore’s Cross-Cultural Communication Model – one method to aid in the process of overcoming cultural barriers and forming a smooth, global workplace. Evaluation Paper 13 of 13 RESOURCES Chandler, Daniel (1995). The transmission model of communication. Retrieved February 24, 2007, from http://www.aber.ac.uk/media/Documents/short/trans.html. DENSO International America, Inc. (2005) Shoulder to shoulder: working effectively with the japanese, (1st ed.). Koga, Ellen L. Griffin, Elm (1997). Information theory of claude shannon & warren weaver. In A first look at communication theory (Chapter 4). Retrieved February 24, 2007, from http://www.afirstlook.com/archive/information.cfm?source=archther Hofstede, Geert (2003). Geert hofstede cultural dimensions for international business. Retrieved February 24, 2007, from www.geert-hofstede.com. International Business Center (2007). Geert hofstede: cultural insights for international business, Retrieved February 24, 2007, from http://www.cyborlink.com/besite/hofstede.htm Wikipedia (2006). Shannon-weaver model, Retrieved February 24, 2007, from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Shannon-Weaver_model.