Test Equity in Vocational Evaluation

advertisement

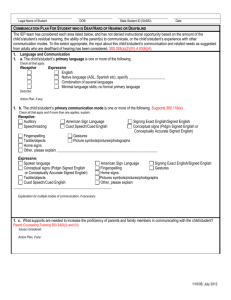

Equity 1 Test Equity in Vocational Evaluation Steven R. Sligar, Ed.D., CVE, PVE East Carolina University Testing involves selecting, administering, scoring, interpreting, and reporting results. This testing process directly involves the test taker and the test user with the results affecting them as well as families, administrators, teachers, employers, policy makers, test developers, and others. One factor that undergirds the entire process is the fairness and impartiality of the test or test equity. This topic is addressed in general by the American Psychological Association from the perspectives of test user qualifications (DeMers, August 2000) and test taker responsibilities (Geisinger, n.d.). The Association for Assessment in Counseling prepared Responsibilities of Users of Standardized Tests (Wall et al., 2003) that also addresses equity issues. Equity is addressed by the codes of ethics for rehabilitation professionals, e.g., vocational evaluators (see http://pveregistry.org/ and http://vecap.org/) and rehabilitation counselors (see http://www.crccertification.com/). Ekstrom and Smith (2002) in their book on assessing individuals with disabilities stress the foundation for accommodations is equity. Specifically, PEPNet convened a test equity summit to make plans to address equity for persons who are deaf or hard of hearing (Loew & Mounty, 2008). There are numerous examples of the importance of test equity in a variety of areas and one related to employment is applicable to this discussion. In the process of becoming a Certified Rehabilitation Counselor (CRC), candidates must pass an examination to demonstrate they have the basic knowledge to practice. Passing the test and obtaining the CRC credential can have many positive influences on the counselor’s career path, which makes the Commission on Equity 2 rehabilitation Counselor Certification (CRCC) examination a high stakes test. Some of the candidates are counselors who are deaf or hard of hearing and meet all of the requirements to sit for the examination. A high percentage of these candidates do not pass the test because it is not in the candidates’ native language, the items may not be culturally relevant, and the test is not an accurate indicator of their counseling skills. In a response to this situation, the CRCC convened an Advisory Panel of experts that published a list of recommendations that serve to contextualize the scope of test equity. Briefly, these recommendations are: involve individuals who are deaf or hard of hearing in the process of test item creation; assess the reading level of the test; obtain feedback from previous test takers about the items and language; inform candidates about accommodations; and develop study guides (Reid & Nunez, n.d.). Clearly equity is an important issue because candidates may be denied access to career development and to correct the problem requires a multi-faceted approach that is neither quick nor inexpensive. Premises There are two underling premises in this discussion of test equity: practitioner preparedness and the importance of corroborative information. In order to initiate the testing process the practitioner must master two knowledge domains and one skill area. First, is the development of a deep knowledge of deafness, which includes special training in the biological/psychological/social aspects of deafness and both a formal study of and personal familiarity with the culture of people who are Deaf and the community of persons who are deaf or hard of hearing. Second, the practitioner must develop skills in American Sign Language and be familiar with other forms of manually coded English and gestural systems. Third, is the importance of mastering the discipline of evaluation, which is typically recognized as masters Equity 3 degree preparation with appropriate credentialing. This premise is not given to gate keep the field but rather to serve as a guide for professional development (if you are developing as a professional in deafness rehabilitation and evaluation) or as a way to present/describe your skills if you are in practice. For more details related to human resource management and related skills development refer to the (Twenty-Fifth Institute on Rehabilitation Issues, 1999, pp. 52-69). The second premise relates directly to the practice of testing persons who are deaf or hard of hearing and that premise is the use of corroborative information. The practitioner must conduct a thorough review of background information. While the practitioner gleans the file containing other professional reports, it is important to maintain a critical eye to evaluate the incremental validity of the information. For example, a consumer who graduated from a school for the Deaf and uses sign language has a greater risk of misdiagnosis if the test user does not know deafness. On the other hand, a test user who is Deaf and uses sign language may also misdiagnose a person who is hard of hearing and attended a mainstream special education program. Either one of the test users may provide accurate results but it is incumbent on the reader to determine the accuracy and utility of the information. Another part of corroborative information involves the use of a clinical interview with the consumer and collateral interviews with individuals who know the consumer. This interview data may help with test selection because tests must be chosen that are a best match with the consumer’s communication background. Data interpretation is also influenced by the corroborative information. For more information on interviews see Bolton & Parker (2008), Power (2006), or another textbook on evaluation or assessment. Cheung (1983) offers insight into the review of referral information and interview for persons who are considered low functioning and deaf (LFD; see 25th IRI for more information on the term LFD). Equity 4 Tools Vocational evaluation is a profession that assesses the knowledge, skills, and abilities of people with disabilities or who are disadvantaged to choose, get, and keep a job. Vocational evaluators use three tools: instruments, techniques, and strategies (Thomas, 1997). Instruments include tests, which are of primary interest in this paper, and work samples. Techniques include situational and community-based assessments, ecological evaluations, and improvised tasks. Strategies are twofold: legally mandated accommodations and modifications to instrument or technique administration to identify learning styles/preferences and natural supports. The following discussion focuses on three types of tests commonly used in vocational evaluation as well as 14 tests representative of each type. None of the tests are standardized with persons who are deaf or hard of hearing (except the Stanford Achievement Test-Tenth Edition; SAT-10). All of the tests may be used by a professional with a masters degree and who has completed a course in testing. This qualification is based on the old APA levels and is often reported on vendor web sites as level B. All of the tests are designed to be used with adults and if the norms are different then this is noted. Neither time nor space permits a thorough discussion of each test so the focus is on implications of using the test with persons who are deaf or hard of hearing. These implications include whether or not the test is timed, the reading level of the test (if available), and the use of spoken words or auditory responses in the test’s administration. For the reader who wants more specific information (e.g., psychometric properties, standardization), refer to the companion document for the webcast that presents a table of the tests or refer to the Buros Mental Measurements Yearbook or a textbook on testing and measurement. To close this discussion a protocol of test administration is offered. Equity 5 Achievement Achievement tests are designed to measure learning that has occurred in school. Reading, language or spelling, and math are the three areas most commonly assessed (Klukas, 2005, p. 114). In vocational evaluation these tests are usually administered early in the process to help identify other appropriate instruments or techniques. Achievement tests can be categorized according to the amount of time required for administration into two types: brief and comprehensive. One brief and three comprehensive tests are discussed. Wide Range Achievement Test 4 (WRAT4). This brief test measures spelling, reading, sentence comprehension (all untimed, which is a plus), and math (computations; timed). Problems with the test include dictation of words to be spelled, pronunciation by the test taker on the reading, and sentence comprehension is spoken (this can be interpreted). The WRAT4 is useful as a quick screening for job requirements. Available from http://www4.parinc.com Adult Basic Learning Examination (ABLE). This comprehensive test measures vocabulary, reading comprehension, language (spelling and language), and mathematics (number operations and problem solving; all are untimed). There are three levels based on the number of years of schooling completed (Level 1=1-4 years; Level 2=5-8 years; Level 3= >8 years and may/may not have graduated high school). Level 1 vocabulary and problem solving are dictated. The ABLE is useful in adult basic education programs to determine starting point and in workplace literacy programs. Available from http://www.pearsonassessments.com Stanford Achievement Test –Tenth Edition for use with Deaf or Hard of Hearing (SAT-10). This comprehensive test assesses reading and provides a Lexile measure (reading level score matched to specific texts), mathematics, language, spelling, listening, science, and social science (all untimed). Norms on students who are deaf or hard of hearing are included. Equity 6 The scores may be helpful to determine placement for a student who is in transition to postsecondary education but are not helpful when scores are compared against job requirements because the test was designed for students in K-12. Materials available from the publisher http://www.pearsonassessments.com and Gallaudet Research Institute http://research.gallaudet.edu/Assessment/sat-faq.php Woodcock-Johnson III Tests of Achievement (WJ III ACH). This comprehensive test has two separate batteries: Tests of Cognitive Abilities and Tests of Achievement. This review focuses on the latter, which has a Standard Battery (12 subtests) and an Extended Battery (10 subtests). 19/22 subtests are untimed and 4 are oral language subtests. Several subtests rely on hearing (words, sounds, taped story), use of metaphors, and sound awareness. The evaluator can select a specific area to be measured—may use individual sections, which increases efficiency and the parts that rely on hearing may be omitted. WJ III ACH may be used to identify the instructional level needed by the consumer as well as needed services. Available from http://www.riversidepublishing.com/ Aptitude Aptitude tests are designed to assess innate abilities and acquired abilities that are developed through the influences of daily life (Roberts, 2005, pp. 157-186). The different types of aptitude tests include: work samples; special abilities (psychomotor); mechanical ability (typically paper and pencil); clerical and computer-related; artistic, musical and other creative abilities; and multiple-aptitude batteries (Aiken, 2000). Power (2006) notes that aptitude tests should be considered as indicators of potential and not predictors. There are numerous aptitude or abilities tests on the market and three are reviewed as exemplary of those that may be used with persons who are deaf or hard of hearing. Equity 7 Career Ability Placement Survey (CAPS). This multiple-aptitude battery measures eight ability dimensions: mechanical reasoning, verbal reasoning, numerical ability, language usage, word knowledge, spatial relations, perceptual speed and accuracy, and manual speed and dexterity. A sixth grading reading level is required for overall administration but three dimensions do not rely on reading (latter three from list). Each subtest may be administered individually to measure a specific dimension or the entire battery administered with the results providing a list of possible jobs. Note the norm groups are either high school or college students. The results may be useful to match a specific dimension with a job requirement or the entire battery may be helpful in career counseling for students in transition or in a postsecondary program to select a major. Available from http://www.edits.net O*Net Ability Profiler (AP). This multiple-aptitude battery measures 9 abilities with 11 subtests: verbal, arithmetic reasoning, clerical perception (all 3 require a 6th grade reading level), computation, spatial ability, form perception, motor coordination, manual dexterity (2 subtests), and finger dexterity (2 subtests). Note the latter 6 abilities (8 subtests) do not require reading to perform the task but to read the instructions, which can be interpreted. All of the subtests are timed. Results provide an ability profile with related career information that is linked to the O*Net, which is useful in career counseling with students, new job seekers, or consumers in occupational transition. Available from http://www.onetcenter.org/AP.html?p=2 Crawford Small Parts Dexterity Test (CSPDT). This single trait test is representative of similar tests with a narrow yet specific focus: the CSPDT is designed to measure eye-hand coordination and fine motor dexterity of applicants for jobs requiring these skills. The CSPDT is easy to administer, it may be timed or untimed, and no reading is required. The oral instructions may easily be demonstrated or signed. It is useful as a screening tool for the target jobs, though Equity 8 its intended use may not be apparent to the test taker (face validity). Available from http://www.talentlens.com/en/ Intelligence The Occupational Network Online content model (O*Net; n.d.) describes intelligence as one of many abilities, which are enduring attributes of an individual that influence performance. Specifically, the O*Net defines 21 cognitive abilities that influence the acquisition and application of knowledge in problem solving. Thus, intelligence is considered as an aptitude but given the numerous tests and importance of assessment in this area—it is often reviewed as a separate category. Traditionally, IQ tests have been categorized as either verbal, performance, or combined. This classification is changing as evidenced by the four index scores that comprise the full scale IQ of the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Test (WAIS). However, for purposes of this review the traditional classification is used. The results of the three following tests can be used as an indicator of problem solving skills and potential for success in school or on the job. Beta-III. This performance (non-verbal) test is comprised of five timed subtests: coding, picture completion, clerical checking, picture absurdities, and matrix reasoning. The oral instructions are easy to sign or demonstrate. No reading is involved. When combined with corroborative information, this test may prove useful in matching applicant ability with job requirements (job readiness) or support for continued training, such as an adult education class or on the job training. Available from http://www.pearsonassessments.com/ Shipley-2. This test is a measure of general intellectual functioning in verbal and abstract (performance) reasoning that uses three timed subtests: vocabulary, abstraction, and block patterns. Reading is part of the instructions but the level is not specified. The test taker reads the instructions, which are straight forward and could easily be signed, however the content may Equity 9 prove difficult for many consumers with lower reading levels (probably <6th grade). The Shipley is widely used in the field of substance use disorders and other acquired cognitive impairments (e.g., brain injury) because it provides an Impairment Index to assist with diagnosis. Available from http://wpspublish.com/ Wonderlic Contemporary Cognitive Ability Test. This is a timed online (paper version available) employment aptitude test and used in the public employment sector to help match job applicant’s abilities with jobs. The instructions are provided orally or read by the test taker on line and the instructions are easily signed. There are 50 questions, which must be read by the test taker. The reading level is not provided but the content may prove difficult for many consumers with lower reading levels (probably <6th grade). Available from http://www.wonderlic.com/ Interest Interest inventories are a useful tool for rehabilitation professionals to help consumers choose a job (Bolton & Parker, 2008). The inventories have developed concurrent with career development theories and the most prominent theory is trait and factor (Peters, 2005). Interest inventories (not tests—there is no right or wrong answer) are frequently administered at the start of evaluation to help determine which work samples or situational assessments are to be used. Inventories are most helpful when they are linked to occupational categories or resources such as the Dictionary of Occupational Titles ( DOT), O*Net, or Occupational Outlook Handbook or to a clearly stated theoretical base, such as the Holland codes (Realistic, Investigative, Artistic, Social, Enterprising, and Conventional or RIASEC). All of the inventories are self-report and based on either a description/depiction of job tasks or names of jobs. There are two basic interrelated premises concerning interest testing that may be problematic for persons who are deaf or hard of hearing. First relates to the development of self-reflection skills, which may be Equity 10 hampered by deprivation of social and vocational information (the second premise—that the test taker is able to make an informed decision). In other words, how is a person who is deaf supposed to select a job or a work task with no familiarity of the depicted activity? One way to categorize interest inventories is by written or pictorial presentation of the items and two of each are discussed. O*Net Interest Profiler. This inventory presents 180 written work tasks and the test taker must indicate Like, Dislike, or Unsure. The readability level is approximately 8th grade and the inventory is untimed. The results are provided as Holland Codes and linked to the O*Net. The user’s guide clearly states the results are intended for career exploration and vocational counseling—not hiring decisions. Available from http://www.onetcenter.org/IP.html Self-Directed Search (SDS). This untimed inventory is self-administered, scored, and interpreted. It has four forms and two are presented: Form R for adults who read at a 7th-8th grade level and Form E (Easy) for adults at the 4th grade level. The instructions must be read and are easily interpreted. However, the items require self-reflection because the consumer must list Occupational Daydreams, and choose Activities, Competencies, Occupations, and Selfestimates. The results provide Holland codes with an Occupation Finder that has a listing of approximately 1300 job titles. These are linked to the DOT. The results provide information for career counseling. Available from http://wpspublish.com/ Reading-Free Vocational Interest Inventory: 2 (RFVII:2). This untimed instrument is designed for use with persons with limited reading abilities and was standardized on people who have an intellectual disability, learning disability, are disadvantaged, or in a regular classroom. The pictorial items consist of 55 sets of black and white drawings in triads and the consumer must select one that s/he would like to do. The instructions are easily signed. A basic premise is Equity 11 that the consumer will know what the pictures represent and then be able to make a selection. The work activities portrayed are mostly unskilled with some semi-skilled. The results are presented in 11 vocational interest areas and 5 clusters with no link to career resources or a theoretical foundation. The obtained information may be useful in vocational counseling. Available from http://www.proedinc.com/ Wide Range Interest and Occupation Test (WRIOT2). This untimed instrument is designed for people with a wide range of literacy and language levels (limited to college), learning disabilities, and reading problems. The 238 color pictures are presented in a booklet or via computer and the consumer must indicate like, dislike, or undecided about each picture. The instructions are easily signed. The work activities vary from unskilled to professional. There are 39 scales and these are presented in three clusters: Occupations, Interests, and Holland Type. The information is useful as a career counseling tool. Available from http://www.pearsonassessments.com/ Order of Administration The order of administration of tests has an influence on the testing process. For many consumers who are deaf or hard of hearing more academically oriented testing may serve to heighten their anxiety, cause poor performance, and they may even leave the evaluation. In this instance, starting with hands on physical capacity or aptitude testing may serve to reduce anxiety and permit time to develop rapport. Using background information, then the evaluator may be in a better position to administer a brief achievement test followed by an interest inventory and further aptitude testing. On the other hand, for students who are interested in a postsecondary program, then they may expect to have some type of assessment of their academic skills. Therefore, an achievement test may be best at the onset of evaluation followed by an interest Equity 12 inventory, and further aptitude testing. When the testing is complete the evaluator will have to make the decision to continue with another evaluation tool, such as a situational assessment, or to conduct further testing. Summary There is an old English proverb; you can't make a silk purse out of a sow's ear that is applicable to test equity with persons who are deaf or hard of hearing. To paraphrase: how can you obtain fair and equitable (useful) information from tests that are not designed for persons who are deaf or hard of hearing? An analysis of the three variables (see Table 1) relative to testing shows the following: Timing: Six tests were timed, six untimed, and two were combined. A person who is deaf or hard of hearing may take longer to process English based items and consequently need more time. Reading levels: The four achievement tests varied, five tests required at least a 6th grade reading level, one a 4th grade level, and three no reading. Considering the average grade level of a high school graduate who is deaf or hard of hearing (somewhere between 4th -6th grade) most of these tests are not appropriate. The test user will need to delve further into the items because such statements as “handling bank accounts” or “run a dairy farm” (taken from an interest inventory) are loaded with possible language problems (translating from English to ASL). Handling may be misinterpreted as touching (to handle) money and how does a dairy farm ambulate rapidly (run)? Equity 13 Administration: Nine of the tests use combined oral/written methods for administration, two are oral only, two are written only, and one has some deafness considerations. The method of administration clearly shows the presence of the dominant hearing culture and the critical importance of proper test selection. None of these tests were originally designed for use with people who are deaf or hard of hearing (the SAT-10 was standardized with students who are deaf and hard of hearing but the test was not originally constructed with this population in mind). However, all of these tests can be used with specific types of people who are deaf or hard of hearing. The evaluator who knows deafness and the tests will be able to select a test that is a fit with the consumer’s educational and communication background, administer the test, and obtain useful results (see Appendix for suggested matches). Table 1 Three Variables Relative to Testing Persons who are Deaf or Hard of Hearing Test Timed Reading Level Administration WRAT4 Yes Varies Oral / Written ABLE No Varies Oral / Written SAT-10 No Varies Deafness WJ III ACH Both Varies Oral / Written CAPS Yes 6th Oral / Written O*Net AP Yes 6th / NA Oral / Written CSPDT Both NA Oral BETA-III Yes NA Oral / Written Shipley-2 Yes 6th Oral / Written Wonderlic CCAT Yes 6th Oral / Written Equity 14 O*Net IP No 8th Oral / Written SDS No 4th Written RFVII:2 No NA Oral WRIOT2 No NA Oral / Written References Aiken, L. (2000). Psychological testing and assessment. Boston: Allyn and Bacon. Bolton, B. F., & Parker, R. M. (Eds.). (2008). Handbook of measurement and evaluation in rehabilitation (Fourth ed.). Austin, TX: Pro-ed. Cheung, F. (1983). Vocational evaluation of severely disabled deaf. In D. Watson, G. Anderson, P. Marut, S. Ouellette & N. Ford (Eds.), Vocational evaluation of hearing impaired persons: Research and practice (1st ed., pp. 57-67). Little Rock, AR: University of Arkansas Rehabilitation Research and Training Center on Deafness and Hearing Impairment. DeMers, S. T. (August 2000). Report of the task force on test user qualifications. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. Ekstrom, R. B., & Smith, D. K. (2002). Assessing individuals with disabilities in educational, employment, and counseling settings. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. Geisinger, K. F. (n.d.). Rights and responsibilities of test takers: Guidelines and expectations. Retrieved August 11, 2011, from http://www.apa.org/science/programs/testing/rights.aspx Klukas, G. (2005). Achievement tests. In D. F. Roberts (Ed.), Test review manual for vocational evaluators (pp. 112-156). Athens, GA: Elliott & Fitzpatrick. Loew, R., & Mounty, J. (2008). Test equity for individuals who are deaf or hard of hearing PEPNet. Retrieved from http://resources.pepnet.org/files/356_2010_2_1_16_35_PM.pdf O*Net (n.d.). The O*Net content model. Retrieved from http://www.onetcenter.org/dl_files/ContentModel_DetailedDesc.pdf Peters, R. H. (2005). Interest inventories and vocational evaluation. In D. F. Roberts (Ed.), Test review manual for vocational evaluators (pp. 68-111). Athens, GA: Elliott & Fitzpatrick. Power, P. W. (2006). A guide to vocational assessment. (4th ed.). Boston: Pro-Ed. Reid, C., & Nunez, P. (n.d.). Exploring examination equity issues for certified rehabilitation counselor candidates who are deaf or hard of hearing. Schaumburg, IL: Commission on Rehabilitation Counselor Certification. Roberts, R. (2005). Aptitude tests. In D. F. Roberts (Ed.), Test review manual for vocational evaluators (pp. 157-186). Athens, GA: Elliott & Fitzpatrick, Inc. Equity 15 Thomas, S. W. (1997). Vocational evaluation and assessment: Philosophy and practice. Greenville, NC: East Carolina University. Twenty-Fifth Institute on Rehabilitation Issues. (1999). In D. W. Dew (Ed.), Serving individuals who are low-functioning deaf. Washington, DC: George Washington University Regional Rehabilitation Continuing Education Program. Wall, J., Augustin, J., Eberly, C., Erford, B., Lundberg, D., & Vansickl, T. (2003). Responsibilities of users of standardized tests (3rd ed.) Association for Assessment in Counseling. Retrieved from http://aac.ncat.edu/documents/rust.html Appendix Overall Test Match with Communication Preference Test WRAT4 ABLE SAT-10 WJ III ACH CAPS O*Net AP CSPDT BETA-III Shipley-2 Wonderlic CCAT O*Net IP SDS RFVII:2 WRIOT2 Deaf-ASL +/+/+ +/+/+/+ +/+/+ + Deaf-English Late Deafened + + + + + + + + + + + + + + Author contact information: Steven R. Sligar, Ed.D., CVE, PVE Associate Professor and Director Graduate Program in Vocational Evaluation Department of Rehabilitation Studies College of Allied Health Sciences, Mail Stop 677 East Carolina University Greenville, NC 27858-4353 252-744-6293 office 252-744-6302 fax sligars@ecu.edu Hard of Hearing + + + + + + + + + + + + + +