APUSH: Chapter 17 Industrial Supremacy Reading List: #6: Andrew

advertisement

APUSH: Chapter 17 Industrial Supremacy

Reading List:

#6: Andrew Carnegie Becomes a Businessman (1868)

#20: The Sweatshops of Chicago

Social Darwinism and American Laissez-faire Capitalism

18.1: Andrew Carnegie, from "The Gospel of Wealth" (1889)

Andrew Carnegie Becomes a Businessman

Andrew Carnegie

Becomes a

Businessman (1868)

Andrew Carnegie came to the United States as a

penniless immigrant from Scotland. However, by the

end oj the nineteenth century he had become a wellknown industrialist and one v] the Wealthiest men in

the world. Carnegie launched his business career in

{868 and eventually amassed a fortune in the steel

industry. His company produced most of the steel

products in the United States by {900. The selection

that follows is taken from an article Carnegie wrote

for a magazine called Youth's Companion in i896,

entitled "How I Served My Apprenticeship As a Businessman." As you read the excerpts, consider what

values Carnegie's autobiography reflects.

I

am sure that I should never have selected a business career if I had been permitted to choose.

The eldest son of parents who were themselves

poor, 1 had, fortunately, to begin to perform some

useful work in the world while still very young, in

order to earn an honest livelihood . . . What I could

get to do, not what I desired, was the question.

When I was born my father was a well-to-do

master-weaver in Dunfermline, Scotland. He owned

no less than four damask looms and employed apprentices. This was before the days of steam factories

for the manufacture of linen. A few large merchants

took orders and employed "master-weavers," such as

my father, to weave the cloth, the merchants

supplying the materials.

As the factory system developed, handloom

weaving naturally declined, and my father was one

31

From "How I Served My

Apprenticeship As a

Business Man" by

Andrew Carnegie,

Youth's Companion,

Volume LXX, No. 17

Scottish immigrant Andrew Carnegie rose from

poverty to become one of

the wealthiest industrialists in the United

States.

of the sufferers by the change. The first serious lesson of

my life came to me one day when he had taken in the last

of his work to the merchant and returned to our little home

greatly distressed because there was no more work for him

to do. I was then just about ten years of age, but the lesson

burned into my heart, and I resolved then that "the wolf of

poverty" would be driven from our door some day, if I

could do it.

The question of selling the old looms and start

ing for the United States came up in the family

council

It was finally resolved to take the plunge

and join relatives already in Pittsburgh. I well remember

that neither father nor mother thought the change would be

otherwise than a great sacrifice for them, but that "it would

be better for our two boys. . . ."

Arriving in Allegheny City, four of us,—father,

mother, my younger brother and myself,—father entered a

cotton factory I soon followed and served as a "bobbin

boy," and this is how I began my preparation for

subsequent apprenticeship as a business man. I received

one dollar and twenty cents a week, and was then just about

twelve years old.

I cannot tell you how proud I was when I received my

first week's own earnings. One dollar and twenty cents

made by myself and given to me because I had been of

some use in the world! No longer entirely dependent upon

my parents, but at last admitted to the family partnership as

a contributing member and able to help them! I think this

makes a man out of a boy sooner than almost anything else.

. . . It is everything to feel that you are useful.

. .

For a lad of twelve to rise and breakfast every

morning, except the blessed Sunday morning, and go into

the streets and find his way to the factory, and begin work

while it was still dark outside, and not be released until

after darkness came again in the evening, forty minutes'

interval only being al-

lowed at noon, was a terrible task. . . . But I was young . .

. and something within always told me that ... I should

some day get into a better position . . .

A change soon came, for a kind old Scotsman, who

knew some of our relatives, made bobbins and took me into

his factory before I was thirteen. But here for a time it was

even worse than in the cotton factory, because I was set to

fire a boiler in the cellar, and actually to run the small

steam-engine which drove the machinery

The firing of the boiler was all right, for fortunately

we did not use coal, but the refuse wooden chips, and I

always liked to work in wood. But the responsibility of

keeping the water right and of running the engine, and the

danger of my making a mistake and blowing the whole

factory to pieces, caused too great a strain, and I often

awoke and found myself sitting up in bed through the night

trying the steam-gages But I never told them at home that I

was having a "hard tussle." No! no! everything must be

bright to them.

This was a point of honor, for every member of the

family was working hard except, of course, my little

brother, who was then a child, and we were telling each

other only all the bright things. Beside this no man would

whine and give up—he would the first. . . .

My kind employer, John Hay, peace to his ashes!

soon relieved me of the undue strain, for he needed some

one to make out bills and keep his accounts, and finding

that 1 could write a plain schoolboy hand, and could [work

with numbers], I became his only clerk. . . .

I come now to the third step in my apprenticeship, for

I had already taken two, as you see, the "cotton factory"

and then the "bobbin factory" I obtained a situation as

messenger-boy in the telegraph office of Pittsburgh when I

was fourteen. Here I entered a new world. . . . Amid

books, newspapers,

pencils, pen and ink and writing pads, and a clean office,

bright windows and the literary atmosphere, I was the

happiest boy alive.

My only dread was that I should some day be

dismissed because I did not know the city,- for it is

necessary that a messenger-boy should know all the firms

and addresses of men who are in the habit of receiving

telegrams. But I was a stranger in Pittsburgh However, I

made up my mind that I would learn to repeat successively

each business house in the principal streets, and was soon

able to shut my eyes and begin at one side of Wood Street,

and call every firm to the bottom. Before long I was able to

do this with the business streets generally. . . .

Of course, every ambitious messenger-boy wants to

become an operator, and before the operators arrived in the

early mornings the boys slipped up to the instruments and

practised. This I did and was soon able to talk to the boys

in the other offices along the line, who were also

practising.

One morning I heard Philadelphia calling Pittsburgh

and giving the signal, "Death Message." Great attention

was then paid to "Death Messages," and I thought I ought

to try to take this one. I answered and did so, and went off

and delivered it before the operator came After that the

operators sometimes used to ask me to work for them.

Having a sensitive ear for sound 1 soon learned to

take messages by ear, which was then very uncommon—I

think only two persons in the United States could then do it

Now every operator takes by ear, so easy it is to follow and

do what any other boy can—if you only have to. This

brought me into notice, and finally I became an operator

and received the—to me—enormous [salary] of twentyfive dollars per month, three hundred dollars a year!

This was a fortune, the very sum that I had fixed when

I was a factory-worker as the fortune I wished to possess,

because the family could live on three hundred dollar a year

and be almost, or quite

independent. Here it was at last! But I was soon to [receive]

extra compensation for extra work. The six newspapers of

Pittsburgh received telegraphic news in common. Six copies

of each despatch were made by a gentleman who received six

dollars per week for the work, and he offered me a gold dollar

every week if I would do it, of which I was very glad indeed,

because I always like to work with news and scribble for

newspapers. . . .

I think this last step of doing something beyond one's

task is fully entitled to be considered "business." The other

revenue, you see, was just salary obtained for regular work,

but here was a "little business operation" upon my own

account, and I was very proud indeed of my gold dollar

every week.

The Pennsylvania Railroad shortly after this was

completed to Pittsburgh, and that genius, Thomas A. Scott,

was its superintendent He often came to the telegraph office

to talk to his chief . . . and I became known to him in this

way.

When that great railway system put up a wire

of its own, he asked me to be his "clerk and operator."

So I left the telegraph office . . . and became connected with the railways.

The new appointment was accompanied by a,

to me, tremendous increase of salary. It jumped from

twenty-five to thirty-five dollars per month. Mr Scott

was then receiving one hundred and twenty-five dollars per

month, and I used to wonder what on earth he could do

with so much money.

I remained for thirteen years in the service of the

Pennsylvania Railroad Company, and was at last

superintendent of the Pittsburgh division of the road,

successor to Mr. Scott, who had in the meantime risen to the

office of vice-president of the company

One day Mr Scott, who was the kindest of men, and

had taken a great fancy to me, asked if I had or could find

five hundred dollars to invest.

Here the business instinct came into play. I felt that as

the door was opened for a business invest-

ment with my chief, it would be wilful flying in the face of

providence if I did not jump at it, so I answered promptly:

"Yes, sir, I think I can."

"Very well," he said, "get it, a man has just died who

owns ten shares in the Adams Express Company, which I

want you to buy It will cost you sixty dollars per share,

and I can help you with a little balance if you cannot raise

it all."

Here was a queer position The available assets of the

whole family were not five hundred dollars. . . .

Indeed, had Mr Scott known our position he would

have advanced it himself, but the last thing in the world the

proud Scot will do is to reveal his poverty and rely upon

others.

The family had managed by this time to purchase a

small house, and paid for it in order to save rent. My

recollection is that is was worth eight hundred dollars.

The matter was laid before the council of three that

night, and the oracle [wise one, used here in reference to his

mother] spoke. "Must be done. Mortgage our house I will

take the steamer in the morning for Ohio and see uncle, and

ask him to arrange it. I am sure he can." This was done. Of

course her vi sit was successful—where did she ever fail?

The money was procured, paid over, ten shares of

Adams Express Company stock was mine, but no one knew

our little home had been mortgaged "to give our boy a start"

Adams Express Stock then paid monthly dividends of

one percent, and the first check for ten dollars arrived. I can

see it now, and I well remember the signature of "J. C.

Babcock, cashier . . ."

Here was something new to all of us, for none of us

had ever received anything but from a toil. A return from

capital was something strange and new.

How money could make money . . . led to much

speculation upon the part of the young fellows

[Carnegie's friends], and I was for the first time hailed as a

"capitalist. . . ."

A very important incident in my life occurred when

one day in a train a nice, farmer-looking gentleman

approached me, saying that the conductor had told him I

was connected with the Pennsylvania Railroad, and he

should like to show me something. He pulled from a small

green bag the model of the first sleeping-car. This was Mr

Woodruff, the inventor. . . Its value struck me like a

flash. I asked him to come to Altoona the following week,

and he did so.

Mr. Scott, with his usual quickness, grasped the idea.

A contract was made with Mr Woodruff to put two trial

cars on the Pennsylvania Railroad. Before leaving Altoona

Mr Woodruff came and offered me an interest in the

venture which I promptly accepted. But how 1 was to make

payments rather troubled me, for the cars were to be paid

for jn monthly installments after delivery, and my first

monthly payment was to be two hundred and seventeen

dollars and a half

I had not the money, and I did not see any way of

getting it. But 1 finally decided to visit the local banker

and ask him for a loan, pledging myself to repay at the rate

of fifteen dollars per month. He promptly granted it. Never

shall I forget his putting his arm over my shoulder, saying,

"Oh, yes, Andy, you are all right." I then and there signed

my first note Proud day this, and surely, now, no one will

dispute that I was becoming a "business man." I had signed

my first note and, more important of all,—for any fellow

can sign a note,—I had found a banker willing to take it as

good.

My subsequent payments were made by the [money

received] from the sleeping-cars, and 1 really made my

first considerable sum from this investment in the

Woodruff Sleeping Car Company, which was afterward

absorbed by Mr. Pullman—a remarkable man who is now

known all over the world.

38

Eyewitnesses and Others: Readings in American History, Volume 2

Shortly after this I was appointed superintendent

of the Pittsburgh Division, and returned to my dear

old home, smoky Pittsburgh. Wooden bridges were

then used exclusively upon the railways, and the

Pennsylvania Railroad was experimenting with a

bridge built of cast-iron. I saw that wooden bridges

would not do for the future, and organized a company

in Pittsburgh to build iron bridges.

Here again I had recourse to the bank, because

my share of the capital was twelve hundred and fifty

dollars and I had not the money,- but the bank lent it

to me, and we began the Keystone Bridge Works,

which proved a great success. . . .

This was my beginning in manufacturing,- and

from that start all our other works have grown, the

profits of the one works building the other. My

"apprenticeship" as a business man soon ended, for I

resigned my position as an officer of the Pennsylvania

Railroad Company to give exclusive attention to

business.

I was no longer merely an official working for

others . . . but a full-fledged business man working

upon my own account.

REVIEWING THE READING

i. Carnegie uses his career to suggest certain

values to the youth of the United States.

What are these values?

2. What succession of jobs did Carnegie hold

before he went into business for himself?

3. Using Your Historical Imagination. According to Andrew Carnegie, what did it mean

to be a "real businessman"? Do you think it

means the same thing today?

The Sweatshops of

From The Poor in Great

Cities by Joseph

Kirklaiid.

Chicago (1891)

Prior to the passage of laws regulating wages and working

conditions, many of the poor living in the big cities of the

nineteenth century worked in sweatshops. Sweatshops were

makeshift factories where large numbers of people worked

long hours for little pay on a piecework basis. These

factories were usually crowded, dimly lighted, poorly

ventilated, unsafe, and unsanitary places. Although a

number of industries used the sweatshop system, the worst

working conditions were found in the garment industry. As

you read the following excerpts from a book about the poor

in big cities in the late 18OOs, look for reasons that help to

explain why people were willing to work under these

terrible conditions.

T

he sweat-shop is a place where, separate from the tailor-shop or

clothing-warehouse, a "sweater" (middleman) assembles

journeyman tailors and needle-women, to work under his

supervision. He takes a cheap room outside the dear

[expensive] and crowded business centre, and within the

neighborhood where the work-people live Thus is rent

saved to the employer, and time and travel to the employed.

The men can and do work more hours than was possible

under the centralized system, and their wives and children

can help, especially when, as is often done, the garments are

taken home to "finish." (Even the very young can pull out

basting-threads ) This "finishing" is what remains undone

after the machine has done its work, and consists in

"felling" [sewing the raw edges of] the waists and leg-ends

of trousers (paid at one and one-half cents a pair), and, in

short, all the "felling" necessary on any garment of any

kind. For this service, at

the prices paid, they cannot earn more than from twenty-five to

forty cents a day, and the work is largely done by Italian,

Polish, and Bohemian women and girls.

The entire number of persons employed in these

vocations [jobs] may be stated at 5,000 men (of whom 800 are

Jews), and from 20,000 to 23,000 women and children. The

wages are reckoned by piece-work and (outside the

"finishing") run about as follows:

Girls, hand-sewers, earn nothing for the first month, then

as unskilled workers they get $1 to $1.50 a week, $3 a week,

and (as skilled workers) $6 a week. The first-named class

constitutes fifty per cent of all, the second thirty per cent, and

the last twenty per cent. In the general work, men are only

employed to do button-holing and pressing, and their earnings

are as follows: "Pressers," $8 to $12 a week,- "underpressers," $4 to $7. Cloak operators earn $8 to $12 a week.

Four-fifths of the sewing-machines are furnished by the

"sweaters" (middlemen), also needles, thread, and wax.

The "sweat-shop" day is ten hours, but many take

work home to get in overtime, and occasionally the shops

themselves are kept open for extra work, from which the

hardest and ablest workers sometimes make from $14 to

$16 a week On the other hand, the regular work-season for

cloakmaking is but seven

124

Eyewitnesses and Others: Readings in American History, Volume 2

months, and for other branches nine months, in the

year. The average weekly living expenses of a man

and wife, with two children, as estimated by a selfeducated workman named Bisno, are as follows: Rent

(three or four small rooms), $2, food, fuel, and light

$4,- clothing, $2, and beer and spirits, $1. . . .

A city ordinance enacts that rooms provided for

workmen shall contain space equal to five hundred

feet of air for each person employed,- but in the

average "sweat-shop" only about a tenth of that quantity is to be found. In one such place there were

fifteen men and women in one room, which contained also a pile of mattresses on which some of the

men sleep at night. The closets were disgraceful. In

an adjoining room were piles of clothing, made and

unmade, on the same table with the food of the

family. Two dirty little children were playing about

the floor. . . .

The "sweating system" has been in operation

about twelve years, during which time some firms

have failed, while others have increased their production tenfold. Meantime certain "sweaters" have grown

rich,- two having built from their gains tenementhouses for rent to the poor workers. The wholesale

clothing business of Chicago is about $20,000,000 a

year.

REVIEWING THE READING

1. Who was the "sweater"?

1. What was "finishing" and how much could

be made doing it?

3. Using Your Historical Imagination. What

were the advantages of the sweatshop system to the "sweater"? How do you explain

the fact that workers were willing to come

to work in the sweatshops?

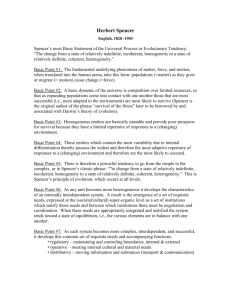

Social Darwinism

and American

laissez-faire

Capitalism

The "Fittest" and the

"Unfit-Herbert Spencer based

his concept of social evolution.

popularly known as "Social

Darwinism," on individual

competition. Spencer believed

that competition was "the law of

life" and resulted in the

"survival of the fittest."

British philosopher Herbert

Spencer went a step beyond

Darwin's theory of evolution

and applied it to the develop

ment of human society. In the

late 1800s, many Americans

enthusiastically

embraced

Spencer's "Social Darwinism" to

justify laissez-faire, or unrestricted, capitalism.

fn 1859. Charles Darwin published Origin of Species, which

explained his theory of animal and

plant evolution based on "natural

selection."

Soon

afterward,

philosophers, sociologists, and

others began to adopt the idea that

human society had also evolved.

"Society advances," Spencer

wrote, "where its fittest members are allowed to assert their

fitness with the least hindrance." He went on to argue

that the unfit should "not be

prevented from dying out."

Unlike

Darwin,

Spencer

Herbert Spencer (1820-1903) applied Charles

Darwin's ideas about evolution to society. He believed believed that individuals could

that keeping government limited would ensure the genetically pass on their learned

"survival of the fittest." (Peny-Castaheda Library. characteristics to their children.

University of Texas at Austin)

This was a common. but

The British philosopher Herbert Spencer wrote about

these ideas even before Darwin's book was published.

He became the most influential philosopher in applying Darwin's ideas to social evolution. Born in 1820,

Herbert Spencer taught himself about the natural sciences. For a brief time, he worked as a railroad surveyor and then as a magazine writer. Spencer never

married, tended to worry a lot about his health, and

preferred work to life's enjoyments.

In 1851, he published his first book. He

argued for laissez-faire capitalism, an economic system that allows businesses to operate with little government interference. A year

later, and seven years before Darwin published Origin of Species, Spencer coined the

phrase "survival of the fittest."

Darwin's theory inspired Spencer to write

more books, showing how society evolved.

With the financial support of friends, Spencer

wrote more than a dozen volumes in 36 years.

His books convinced many that the destiny of

civilization rested with those who were the

•'fittest."

erroneous, belief in the 19th century. To Spencer, the

fittest persons inherited such qualities as

industriousness, frugality, the desire to own property,

and the ability to accumulate wealth. The unfit

inherited laziness, stupidity, and immorality.

According to Spencer, the population of unfit people

would slowly decline. They would eventually become

extinct because of their failure to compete. The government. in his view, should not take any actions to

prevent this from happening, since this would go

against the evolution of civilization.

Spencer believed his own England and other

advanced nations were naturally evolving into peaceful "industrial" societies. To help this evolutionary

process, he argued that government should get out of

the way of the fittest individuals. They should have

the freedom to do whatever they pleased in competing

with others as long as they did not infringe on the

equal rights of other competitors.

Spencer criticized the English Parliament for "overlegislation." He defined this as passing laws that

helped the workers, the poor, and the weak. In his

opinion, such laws needlessly delayed the extinction

of the unfit.

Spencer's View of Government

Herbert Spencer believed that the government should

have only two purposes. One was to defend the nation

against foreign invasion. The other was to protect citizens and their property from criminals. Any other government action was "over-legislation."

Spencer opposed government aid to the poor. He said

that it encouraged laziness and vice. He objected to a

public school system since it forced taxpayers to pay

for the education of other people's children. He

opposed laws regulating housing, sanitation, and

health conditions because they interfered with the

rights of property owners.

Spencer said that diseases "are among the penalties

Nature has attached to ignorance and imbecility, and

should not, therefore, be tampered with." He even

faulted private organizations like the National Society

for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children because they

encouraged legislation.

In the economic arena, Spencer advocated a laissez-faire

system that tolerated no government regulation of private

enterprise. He considered most taxation as confiscation of

wealth and undermining the natural evolution of society.

Spencer assumed that business competition would prevent

monopolies and would flourish without tariffs or other

government restrictions on free trade. He also condemned

wars and colonialism, even British imperialism. This was

ironic, because many of his ideas were used to justify

colonialism. But colonialism created vast government

bureaucracies. Spencer favored as little government as

possible.

Spencer argued against legislation that regulated

working conditions, maximum hours, and minimum

wages. He said that they interfered with the property

rights of employers. He believed labor unions took

away the freedom of individual workers to negotiate

with employers.

Thus, Spencer thought government should be little

more than a referee in the highly competitive "survival

of the fittest." Spencer's theory of social evolution,

called Social Darwinism by others, helped provided

intellectual support for laissez-faire capitalism in

America.

Laissez-faire Capitalism in America

Historians often call the period between 1870 and the

early 1900s the Gilded Age. This was an era of rapid

industrialization, laissez-faire capitalism, and no

income tax. Captains of industry like John D.

Rockefeller and Andrew Carnegie made fortunes.

They also preached "survival of the fittest" in business.

American scholars like sociologist William Graham

Sumner praised the new class of industrial millionaires. Sumner argued that social progress depended on

the fittest families passing on their wealth to the next

generation.

According to the Social Darwinists, capitalism and

society itself needed unlimited business competition to

thrive. By the late 1800s, however, monopolies, not

competing companies, increasingly controlled the production and prices of goods in many American industries.

Workers' wages and working conditions were unregulated. Millions of men, women, and children worked

long hours for low pay in dangerous factories and

mines. There were few work-safety regulations, no

worker compensation laws, no company pensions, and

no government social security.

Although wages did rise moderately as the United

States industrialized, frequent economic depressions

caused deep pay cuts and massive unemployment.

Labor union movements emerged, but often collapsed

during times of high unemployment. Local judges,

who often shared the laissez-faire views of employers,

issued court orders outlawing worker strikes and boycotts.

Starting in the 1880s, worker strikes and protests

increased and became more violent. Social reformers

demanded a tax on large incomes and the breakup of

monopolies. Some voiced fears of a Marxist revolution. They looked to state and federal governments to

regulate capitalism. They sought legislation on working conditions, wages, and child labor.

Social Darwinism and the Law

Around 1890, the U.S. Supreme began aggressively

backing laissez-faire capitalism. Supreme Court

Justice Stephen J. Field asserted that the Declaration of

Independence guaranteed "the right to pursue any lawful business or vocation in any manner not inconsistent

with the equal rights of others ---"

The Supreme Court ruled as unconstitutional many

state laws that attempted to regulate such things as

working conditions, minimum wages for women, and

(Continued on next page)

child labor. The courts usually

based their decisions on the Fifth

and 14th amendments to the

Constitution. These amendments

prohibited the federal and state

governments from depriving

persons of "life, liberty, or property, without due process of law."

(The Supreme Court interpreted

"persons"

as

including

corporations.)

By 1912, both the federal government and many states had adopted

Progressive reform legislation

aimed at ending child labor and

improving working conditions. That

year saw three major candidates for

president, all espousing Progressive

ideas (Democrat Woodrow Wilson,

Republican Howard Taft, and

Progressive Theodore Roosevelt,

who had broken from the

Republicans because he believed

Taft was not progressive enough).

The idea of passing more laws to

correct society's ills had replaced

the Social Darwinist view that civilization best advanced when the

"fittest" had their way while the

"unfit" were allowed to die out.

Americans had increasingly come to

believe that society could choose its

future, which might require government regulations on private enterprise.

In 1905, the U.S. Supreme Court

used the "due process" reasoning

to strike down a New York health

law that limited the workweek of

bakers to 60 hours. The majority

of the justices held that this law

violated the 14th Amendment's

"liberty" right of employers and

workers to enter into labor Charles Darwin < 1809-1882) was probably greatest

contracts. In a famous dissent, scientist of the 19th century. Darwin s theory of evolution

however, Justice Oliver Wendell explained how species evolved over time. He did not

believe in Social Darwinism. (Perry-Castahcda Library,

Holmes criticized the majority University of Texas at Austin)

decision. In a memorable phrase,

he said: "The 14th Amendment does not enact Mr.

In England, Herbert Spencer grew

Herbert Spencer's Social Statics [one of Spencer's

increasingly pessimistic as he witnessed a swelling tide

books on Social Darwinism]." [Lochner v. New York

of legislation that attempted to end the evils of industri198 U. S. 45 (1905)]

alization and laissez-faire capitalism. Spencer died in

1903 and was buried in the same London cemetery as

In 1890, reformers got Congress to pass the Sherman

that great enemy of capitalism, Karl Marx.

Antitrust Act. This law focused on "combinations" like

monopolies (also called trusts). It banned them if they

interfered with interstate commerce by eliminating

competition and keeping the prices of goods high.

When cases reached the Supreme Court, however, the

justices largely ignored the control of consumer prices

by monopolies. Instead, the justices focused on the

behavior of "bad trusts" that used unfair tactics against

competitors.

The Supreme Court limited the protest rights of labor

unions in a 1911 case that outlawed some economic

boycotts. The Supreme Court continued to make decisions that weakened unions until the 1930s.

Despite a hostile Supreme Court, Progressive Era

reformers became increasingly successful in curbing

^*he abuses of laissez-faire capitalism. For example,

in 1906, Congress passed the Pure Food and Drug Act

that prohibited companies from selling contaminated

foods and misbranded drugs.

For Discussion and Writing

1. Social Darwinists believed that society naturally

evolved by individual competition and the "survival

of the fittest." Do you agree or disagree? Why?

2. Do you agree or disagree with Herbert Spencer's

view of government? Why?

3. Would you support laissez-faire capitalism in the

United States today? Explain.

/or further heading

Hofstadter, Richard. Social Darwinism in American

Thought. Boston: Beacon Press, 1992 [originally published 1944].

Wiltshire, David. The Social and Political Thought of

Herbert Spencer. Oxford: Oxford University Press,

1978.

ACTIVITY

Aboilsh the Federal Estate Tax?

Some social critics today argue that the United States

is in a new Gilded Age. As evidence of this, they point

to the decrease in government regulation of industry,

recent disclosures of corporate financial abuses, a weak

union movement, and an increased concentration of

wealth among a small percentage of Americans. A current controversy involves attempts to eliminate the federal estate tax.

The federal estate tax, first imposed during the Civil

War, is a tax on inherited assets valued at more than $ 1

million. Called the "death tax" by its critics, this tax

falls on the wealthiest 2 percent of American families.

The highest tax rate for the largest estates is currently

set at 55 percent.

Under President George W. Bush's 2001 tax cut law, the

federal estate tax will gradually decrease until it ends

completely in 2010. But this will not be permanent. In

2011, the estate tax will return at its 2001 rates.

Those in favor of permanently abolishing the federal

estate tax make these arguments:

The "death tax" is a form of government confiscation of wealth earned by individuals who have the

right to pass it on to their heirs.

Individuals who have already paid income and other

taxes should not have their lifetime savings and

property taxed again at death.

• This tax is not just a burden for rich individuals, but

for the owners of family farms and businesses.

•

It is unfair for the federal estate tax to be phased out

and then restored to its 2001 rates in 2011.

Those opposed to permanently abolishing the federal

estate tax make these arguments:

• Not taxing inheritances of extremely wealthy people will create a perpetual class of rich people. The

American ideal is that people should earn their own

wealth.

• Permanently abolishing the federal estate tax is

nothing less than a tax break for billionaires.

• Ending the estate tax will worsen the current federal

budget deficit and cost billions of dollars in lost revenue needed for Medicare, school, environmental,

and other programs.

• Eliminating the estate tax in 2010 and after would

cause a major drop in revenue just when huge numbers of workers will retire and will need Social

Security.

It is fair that the super rich, who benefit the most

from the American economy, pay more taxes than

less wealthy taxpayers.

What do you think is the fair thing to do?

Form small groups to discuss the following proposed

federal estate tax laws. After the discussion, the members of each group should take a vote on what they

believe is the fairest law. Each group should then report

to the class the results and reasons for its vote, including

minority views.

Proposed Federal Estate Tax Laws

1. Permanently and completely abolish the federal

estate tax now.

2. Permanently abolish the federal estate tax after it

phases out in 2010.

3. Restore the federal estate tax after 2010, but exempt

family-owned farms and businesses, raise the value

of taxable estates, and/or reduce the tax rate.

4. Restore the federal estate tax after 2010 at the 2001

tax rate (current law).

5. Permanently and completely restore the federal

estate tax now at the 2001 tax rates.

SOURCES

Acton. Harry Burrows. "Spencer, Herbert." The New Encyclopaedia Britannica

Micropaedia. 2002 ed. • Bruchey, Stuart. Enterprise. The Dynamic Economy of a

Free People. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1990. • Durant, Will.

The Story of Philosophy. The Lives and Opinions of the Greater Philosophers.

New York: Time, 1962 [originally published 1926]. • Heilbroner, Robert L.

"Economic Systems." The New Encyclopaedia Britannica Macropaedia. 2002

ed. • Hook, Janet. "Senate Vote Blocks Repeal of Estate Tax." Los Angeles Times.

13 June 2002:A1+. • Hofstadter, Richard. Social Darwinism in American

Thought. Boston: Beacon Press, 1992 [originally published 1944]. • Krugman,

Paul. "For Richer, How the Permissive Capitalism of the Boom Destroyed

American Equality." New York Times Magazine. 20 Oct. 2002:62+. • "Social

Darwinism." Tlte New Encyclopaedia Britannica Micropaedia. 2002 ed. • Tribe,

Laurence H. "Substantive Due Process of Law." Encyclopedia of the American

Constitution. New York: Macmillan Pub. Co., 1986. • Wiltshire, David. The

Social and Political Thought of Herbert Spencer. Oxford: Oxford University

Press, 1978.

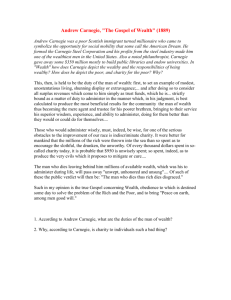

18.1

Andrew Carnegie,

from "The Gospel of Wealth"

(1889)

Written in 1889 for The North American Review, this piece justified the fortunes made by

industrialists like Carnegie and provided a model for the distribution of their wealth. Carnegie

believed laissez-faire economics were tied to social responsibility. Carnegie was born in Scotland

and worked in the United States as a messenger for Western Union and a bobbin boy before.

through shrewd salesmanship and investment, he became the head of Carnegie Steel Company,

which, after it was sold to J. P. Morgan, became United States Steel."

T

he problem of our age is the proper administration of wealth, that the ties of brotherhood may still bind together the rich and poor in

harmonious relationship. The conditions of human life have not only been changed, but revolutionized, within the past few hundred years.

In former days there was little difference between the dwelling, dress, food. and

environment of the chief and those of his retainers... .The contrast between the palace of

the millionaire and the cottage of the laborer with us to-day measures the change which has

come with civilization. This change, however, is not to be deplored, but welcomed as

highly beneficial. It is well, say, essential, for the progress of the race that the houses of some

should be homes for all that is highest and best in literature and the arts, and for all the

refinements of civilization, rather than that none should be so. Much better this great

irregularity than universal squalor. Without wealth there can be no Meccenas.

...to-day the world obtains commodities of excellent quality at prices which even the

preceding generation would have deemed incredible. In the commercial world similar

causes have produced similar results, and the race is benefited thereby. The poor enjoy

what the rich could not before afford. What were the luxuries have become the necessaries of life....

Objections to the foundations upon which society is based are not in order, because

the condition of the race is better with these than it has been with any other which has

* From Andrew Carnegie, "Wealth," North American Review, ]W>.

35

been tried.... NO evil, but good, has come to the race from the accumulation of wealth

by those who have had the ability and energy to produce it....

We start, then, with a condition of affairs under which the best interests of the race

are promoted, but which inevitably gives wealth to the few....What is the proper mode

of administering wealth after the laws upon which civilization is founded have thrown it

into the hands of the few?...

There are but three modes in which surplus wealth can be disposed of. It can be left

to the families of the decedents; or it can be bequeathed for public purposes; or, finally,

it can be administered by its possessors during their lives....

There remains, then, only one mode of suing great fortunes; but in this we have the true

antidote for the temporary unequal distribution of wealth, the reconciliation of the rich

and the poor—a reign of harmony, another ideal, differing, indeed, from that of the

Communist in requiring only the further evolution of existing conditions, not the total

overthrow of our civilization. It is founded upon the most intense Individualism. ...Under

its sway we shall have an ideal State, in which the surplus wealth of the few will become, in

the best sense, property of the man)', because administering for the common good; and this

wealth, passes through the hands of the few, can be made much more potent force for the

elevation of our race than if distributed in small sums to the people themselves. Even the

poorest can be made to see this, and to agree that great sums gathered by some of their

fellow-citizens—spent for public purposes, from which masses reap the principal benefit,

are more valuable to them than if scattered among themselves in trifling amounts through

the course of many years.

If we consider the results which flow from the Cooper Institute, for instance..., and

compare these with those who would have ensured for the good of the man form an

equal sum distributed by Air. Cooper in his lifetime in the form of wages, which the

highest form of distributing, being work done and not for charity, we can estimate of the

possibilities for the improvement of the race which lie embedded in the present law of

the accumulation of wealth....

This, then, is held to be the duty of the man of wealth: lb set an example of modest,

unostentatious living, shunning display or extravagance; to provide moderately for the

legitimate wants of those dependent upon him; and, after doing so, to consider all surplus revenues which come to him simply as trust funds, which he is called upon to

administer, and strictly bound as a matter of duty to administer in the manner which, in

his judgment, is best calculated to produce the most beneficial results for the community—the man of wealth thus becoming the mere trustee and agent for his poorer

brethren, bringing to their service his superior wisdom, experience, and ability to administer, doing for them better than they would or could do for them selves....

In bestowing charity, the main consideration should be to help those who will help

themselves; to provide part of the means by which those who desire to improve may do

so; to give those who desire to rise the aids by which the}' may rise; to assist, but rarely

or never to do all. Neither the individual nor the race is improved by alms giving. Those

worthy of assistance, except in rare cases, seldom require assistance....

The rich man is thus almost restricted to following the examples of Peter Cooper,

Enoch Pratt of Baltimore, Air. Pratt of Brooklyn, Senator Stanford, and others, who

blow that the best means of benefiting the community is to place within its reach the

ladders upon which the aspiring can rise—free libraries, parks, and means of recreation,

by which men are helped in body and mind; works of art, certain to give pleasure and

improve the general condition of the people; in this manner returning their surplus

wealth to the mass of their fellows in the forms best calculated to do them lasting good.

Thus is the problem of rich and poor to be solved. The laws of accumulation will be

left free, the laws of distribution free. Individualism will continue, but the millionaire

will be but a trustee for the poor, intrusted for a season with a great part of the increased

wealth of the community, but administering it for the community far better than if

could or would have done for itself. The best minds will thus have reached a stage in the

development of the race in which it is clearly seen that there is no mode of disposing of

surplus wealth creditable to thoughtful and earnest men into whose hands it flows, save

by using it year by year for the general good....

Such, in my opinion, is the true gospel concerning wealth, obedience to which is destined some day to solve the problem of the rich and the poor, and to bring "Peace on

earth, among men good will."

DOCUMENT ANALYSIS

1. What does Andrew Carnegie assert to be the duty of the "'man of wealth"? Does

Carnegie's formula seem practical?

2. Does Carnegie's "Gospel of Wealth" promote or inhibit democratic opportunity?