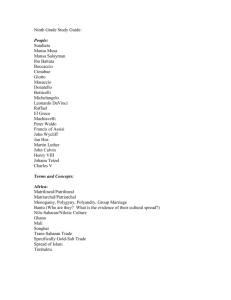

File - The E-Learning Experience

advertisement

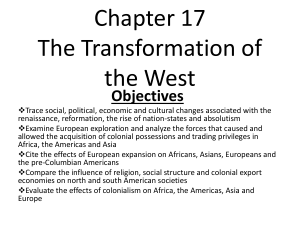

What was the Renaissance and how did it change Medieval Europe? Literally meaning “rebirth” the period known as the Renaissance may be considered as one of the most significant in European history.1 Characterised by religious, intellectual and artistic movements and introducing new values and beliefs, the Renaissance was nothing short of a cultural revolution which initiated the transition of medieval Europe into an era of modernisation. Renaissance Europe experienced great religious change due to opposition from such reformers as Martin Luther. Additionally, individuals such as Francesco Petrarca (Petrarch) fostered the development of humanism, an intellectual movement based on the study of the literary works of Greece and Rome, namely, the classics.2 Emphasis was placed on the potential of individual human ability, provoking a high regard for human worth.3 Another highly notable feature of the Renaissance was the evolution of art. During the fifteenth century, Florentine painters developed a persuasively realistic depiction of the human figure. The realistic portrayal of the human figure became one of the foremost preoccupations of Renaissance art.4 In addition to these movements, the Renaissance experienced significant political reforms. Keeping in mind however, while the Renaissance state was a vast improvement over the feudal anarchy of the Middle Ages, it was still rudimentary and highly inefficient when compared to the modern state.5 There were three main limitations to state building at this time. First, the decentralized chaos of the Middle Ages had given rise to a multitude of local institutions and customs, rights, and inherited titles and offices. The force of tradition with centuries of history to reinforce it made it almost impossible for kings to prohibit them. The parlements for example, could modify the king's laws, delay, or even refuse to enforce them if they thought those laws interfered with long established local customs and traditions. As a result, kings were forced either to work around the old offices by creating new parallel offices that would very gradually take over their 1 VHH, Green, Renaissance and Reformation, London, 1952, pp. 29 WJ Duiker and JJ Spielvogel, The Essential World History to 1500, Third Edition, California, 2008, pp. 279 3 ibid. 4 Duiker and Spielvogel, The Essential World History to 1500, pp. 280 5 C Butler, The Rise of the nation State during the Renaissance, 2007, viewed 14 May 2009, <http://www.flowofhistory.com/units/west/11/FC79> 2 functions, or incorporate the old offices into the new state apparatus, meaning any regularization of government institutions and practices on a national scale was still centuries away. Another problem was the aspirations of the nobles. Although they had suffered from a prolonged decline since the High Middle Ages, they remained somewhat resilient as a class. A major reason being they were still revered as a class and many middle class merchants and bankers were eager to buy noble titles and lands thereby continuing as the nobles of old. A prime example of this was the Fuggers of Augsburg, Germany, the richest banking family in Europe, who bought noble titles and lands and passed into idle noble obscurity. Aiding this process were the kings who, always needing money, sold noble titles and offices to anyone who could pay. As a result, fresh blood infused the nobility with new life. A third problem was the kings' inability (or unwillingness) to stay out of debt and pay their armies and bureaucrats. This encouraged corruption in the government and plundering and desertion by the mercenaries, which further reduced the kings' revenues and ability to pay their bills. Finally, although kings could control their national churches, they could not control the medieval mentality still linking politics and religion. This especially became a problem with the uprise of the Protestants against the Catholics.6 A major influence to the protestant uprise began with Martin Luther. Martin Luther’s Ninety-Five Theses, initiated enormous religious reform, proposing an objection to the Roman Catholic Churches sale of indulgences. To justify the sale of indulgences, Church leaders claimed to have inherited unlimited amounts of good works from Jesus, the credit of which could be sold to believers as indulgences. Ergo, indulgences were portrayed as "confession insurance" against eternal damnation.7 On 31 October 15178, Martin Luther nailed a paper of Ninety-Five Theses against indulgences (paying for remissions of temporal penalty for sin9) to the church door at Wittenberg.10 Although there was nothing unusual about this, as these were not the first theses he had offered for public disputation, nor did they embody necessarily 6 Butler, The Rise of the Nation State During the Renaissance, 2007 J Jones, Against the Sale of Indulgences, Pennsylvania, 2002, viewed 9 May 2009, <http://courses.wcupa.edu/jones/his101%5Cweb%5C37luther.htm> 8 GR Elton, Reformation Europe, 1517-1559, Second Edition, Massachusetts, 1999, pp. 15 9 RW Shaffern, ‘Learned Discussions of Indulgences for the Dead in the Middle Ages’, Church History, vol. 61, no. 4, Dec. 1992, pp. 367-381 10 A Pettegree, The Reformation World, London, 2001, pp. 73 7 revolutionary doctrines, Lutheran countries continue to celebrate this as the anniversary of the Reformation, and justly so. The controversy over indulgences brought together the man and the occasion, signaling the end of the medieval Church.11 Though indulgences were always proclaimed for ostensibly religious purposes, they were revealed to be no more than an important source of papal revenue.12 Thus, the argument proposed in Luther’s theses revealed the Churches extortion of its saints, becoming a foundation for the Protestant reformation. As it developed during the Renaissance, the Protestant Reformation had profound implications, not only for the modern world in general, but specifically for literary history. Just as Renaissance Humanists rejected medieval learning, the Reformation seemed to reject the medieval form of Christianity. Catholics such as Erasmus sought to reform the Church from within. However, Luther's disagreements with Church policy ultimately led him to challenge some of its most fundamental doctrines, therefore leading him and his followers to break away in protest; hence the term Protestants. Among the most important tenets of Protestantism was the rejection of the Pope as spiritual leader. A closely related Protestant doctrine was the rejection of the authority of the Church and its priests to mediate between human beings and God. Protestants believed that the Church as an institution could not grant salvation; only through a direct personal relationship with God (achieved by reading the Bible) could believers be granted such. Many scholars argue that this emphasis on a personal, individual connection with God spawned the modern emphasis on individualism in those cultures affected by Protestantism. However, some Protestants also believed that after the Fall of Adam, human nature was corrupted as far as human spiritual capabilities were concerned. Humans therefore are incapable of contributing to their salvation, for instance through good deeds; it could only be achieved through faith. Overall, there is a good deal of ambivalence regarding many of the Protestant positions, and in fact the disagreement among the many Christian sects may be precisely what distinguishes Renaissance religion from Medieval religion.13 11 Elton, Reformation Europe, 1517-1559, pp. 15 ibid., p. 19 13 Adapted from A Guide to the Study of Literature: A Companion Text for Core Studies 6, Landmarks of Literature, New York, 2009, viewed 13 May 2009, <http://academic.brooklyn.cuny.edu/english/melani/cs6/ren.html > 12 As well as significant religious change due to the development of Protestant beliefs, the Renaissance period produced profound intellectual reforms with the revival of classical learning due to the introduction of humanism. The Renaissance revived classical learning in such a way that it broke with the medieval Christian outlook.14 Where the classical authors were regarded as a source of wisdom on a level with the Bible and the Fathers, and where the Christian texts were rescrutinized in the light of the humanists’ new knowledge of language, literature and history, there was a shift of interest away from the abstractions of theology to the problems of leading the good Christian daily life. Additionally there was a shift of interest from relics, pilgrimages, the invocation of saints, and other popular routes to eternal salvation, to the individual’s direct relationship with God.15 As a result, the teaching of the Fathers, and of the Bible in both of which medieval theologians had been saturated, were treated in such a different way that many of the conventionally accepted beliefs of the Church were discarded.16 Though not anti-Christian, Renaissance individuals embraced the possibilities of this life rather than focusing on the hereafter. Furthermore, instead of renouncing earthly endeavors for contemplation of God, these elites cultivated personal excellence, sought the recognition of their achievements, and explored their own personalities. Individualism in this context was expressed through mastery of the classics. Similar to the thinkers of the Twelfth-Century Awakening, Renaissance scholars valued classical learning. However, unlike their medieval precursors, these scholars delved more deeply into classical texts and appreciated them for their own sake. Renaissance scholars assumed that classical authors could teach them much about life, civic duty, and graceful self-expression. However, these thinkers, unlike their medieval forebears, did not take the classics as timeless wisdom, but studied them critically in their historical context.17 Though in the Renaissance itself humanism was never defined as a philosophy18, it prompted notable works of philosophy, history, and political and social thought. Instructed by Byzantine scholars, many humanists 14 M Perry et al, Humanities in the Western Tradition, First Edition, California, 2003, viewed 9 May 2009, <http://college.hmco.com/humanities/perry/humanities/1e/students/summaries/ch13.html> 15 EN Williams, The Penguin Dictionary of English and European History, 1485-1789, London, 1980, pp. 223 16 Green, Renaissance and Reformation, pp. 32 17 Perry, Humanities in the Western Tradition, 2003 18 CG Nauert, Humanism and the Culture of Renaissance Europe, Cambridge, 2006, pp. 9 mastered Greek and explored Platonism and Aristotle in the original. Under the influence of Greek philosophy, humanists including Ficino, Pico Della Mirandola, and Pompanazzi developed increasingly secular ideas about ethics, the human soul, and the power of reason. Humanists used the works of Cicero as a model for prose and those of Virgil for poetry. As Petrarch said, “Christ is my God; Cicero is the prince of the language.”19 Additionally, humanists often consulted ancient historians for moral and political guidance, cultivating a critical historical awareness which they then applied in their own historical writings.20 Although intellectual reforms were undoubtedly critical towards the modernisation of Europe, perhaps one of the most important reforms was that of Art. Renaissance art broke with the medieval past by emphasizing the human form and the natural world. The principles of mathematical perspective were articulated, defining the Renaissance as a distinct age of cultural rebirth after the period of medieval decay. During the Early Renaissance, sculptors, architects, and painters all made the human figure and its proportions the center of their work. Ghiberti, Brunelleschi, and Masaccio all adapted the principles of linear perspective to their respective arts, while Donatello revived the classical tradition of free-standing sculpture. To capture further how the eye sees the world, Masaccio developed aerial perspective, while both he and Donatello realistically modeled the shapes of their figures. Brunelleschi embodied Renaissance ingenuity by creating an innovative dome for the Florence Cathedral. Other painters—including Fra Fillipo Lippi, Botticelli, and Ghirlandaio—experimented with a variety of techniques, including the use of sensual color, sculptural precision of line, and Flemish-influenced realism. High Renaissance artists absorbed their precursors' innovations and adapted them to a style marked by classical balance, simplicity, and harmony. Leonardo da Vinci pioneered the new style in painting, developing circular motion and pyramidal design to arrange figures both realistically and harmoniously. Michelangelo introduced a new degree of emotional and physical tension into sculpture and, as painter of the Sistine Chapel, skillfully adapted the proportions of his figures to fit the contours of the space while giving them 19 20 Duiker and Spielvogel, The Essential World History to 1500, pp. 279 Perry, Humanities in the Western Tradition, 2003 monumental weight and definition. He also excelled as a poet and an architect, executing his revision of Bramante's plan for St. Peter's in Rome. Raphael brought harmonious pyramidal design to its highest refinement in his Madonna-and-Child paintings and monumental School of Athens. The Venetian style revolutionized color by introducing oil paints. Titian developed this style by modeling his figures through color rather than line, using tone to create individualized portraits. Tintoretto pointed toward Mannerism with his unusual perspective lines and unearthly light.21 The culmination of artistic expression during the High Renaissance – whether in painting, sculpture, or architecture – is one of the glories of the Italian high Renaissance. The thought and experimentation of a multitude of artists since the days of Giotto and Duccio were merged in a great creative triumph, one of the most brilliant in all art history. 22 The intellectual, artistic and religious reforms so characteristic of the European Renaissance23 promoted new ideas, ideals and beliefs which drastically changed individual perspective towards art, religion and individual self. The emphasis placed on individual human ability24 was enough to significantly change the way human beings were depicted, which in turn, had profound effects on the artistic expression on the human body. Broadly speaking, the Renaissance represented a change of outlook as a result of which men began to view the old material of literature and art in a new way, thus arriving at new mental concepts in literature, art and religion.25 The provocative argument regarding indulgences put forth by Martin Luther in his Ninety-Five Theses as a reaction against Church corruption,26 incited protests regarding certain policies of the Church. Consequently, many Catholic saints broke away from the Church, forming Protestant sects. Finally, in regard to the political condition during the Renaissance, although the State had improved significantly since the feudal system of the Middle 21 Perry, Humanities in the Western Tradition, 2003 HS Lucas, The Renaissance and the Reformation, Second Edition, New York, 1934, pp. 298 23 JA Fernández-Santamaría, The Sate, War and Peace: Spanish Political Thought in the Renaissance 1516-1559, New York, 1977 pp. 2 24 Duiker and Spielvogel, The Essential World History to 1500, pp. 279 25 Green, Renaissance and Reformation, pp. 32 26 Adapted from A Guide to the Study of Literature: A Companion Text for Core Studies 6, Landmarks of Literature, 2009 22 Ages, the problems implicated as a result of the kings’ inability to effectively centralise the State, resulted in the hindrance to the significant need for strong political rule.27 27 ibid.