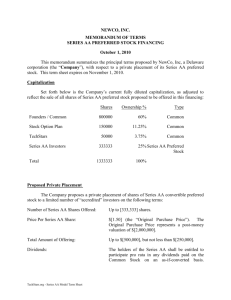

Term Sheet Tutorial: Venture Capital & Angel Investing

advertisement