1 - Personal Webspace for QMUL

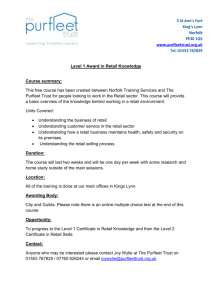

advertisement