Cybercontextualism - Vox Communications

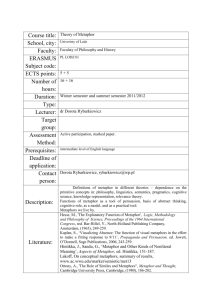

advertisement