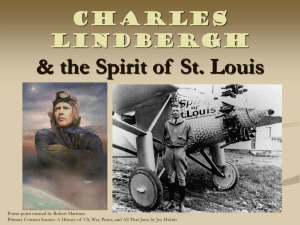

NYC Hotelier Raymond Orteig and “Lucky Lindy”

advertisement

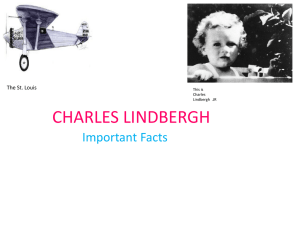

NYC Hotelier Raymond Orteig and “Lucky Lindy” By Stanley Turkel, MHS, ISHC On May 21, 1927, Charles A. Lindbergh completed one of the most famous flights of all time: the first solo nonstop transatlantic flight in history. Lindbergh piloted his plane, the Spirit of St. Louis, 3610 miles between Roosevelt Field on Long Island, New York and Paris, France in 33.5 hours. With that flight, Lindbergh won the $25,000 prize offered by a practically unknown New York City hotel owner. In 1919, a New York hotel owner, Raymond Orteig, issued an extraordinary challenge to the fledgling flying world. Enthralled by tales of pioneer aviators, the French-born Orteig, who owned the Brevoort and Lafayette hotels, offered a purse of $25,000 to be awarded to “the first aviator who shall cross the Atlantic in a land or water aircraft (heavier than air) from Paris or the shores of France to New York, or from New York to Paris without a stop.” Orteig said his offer would be good for five years, but five years came and went without anyone accomplishing this feat. No one even tried. In 1926, Orteig extended the term of his offer for another five years. This time around, however, aviation technology had advanced to a point where some thought that it might, indeed, be possible to fly nonstop across the Atlantic Ocean. Charles A. Lindbergh was one who thought it could happen, but few people believed that this obscure mail pilot had any chance of collecting Orteig’s $25,000 prize. 1 About Orteig. Born in France, Raymond Orteig emigrated to the United States in 1882. He began a career in the hotel and restaurant business and eventually became the maitre d’ at the Lafayette Hotel in New York City, which was located not far from the Brevoort Hotel. In 1902 he purchased the Brevoort, which was known for its basement café. Comprising three adjoining houses on Fifth Avenue between 8th and 9th Streets, the Brevoort had gained a reputation in the late 19th century as a stopping place for titled Europeans. The Brevoort Café’s French character, enriched by Orteig’s yearly wine-buying trips to France and a renovation that Orteig oversaw, attracted an illustrious crowd of Greenwich Village artists and writers. Among them was Mark Twain, lonely but popular, who took up residence between 1904 and 1908 in the Gothic-revival town house located on the southeast corner of Fifth Avenue and East 9th Street. (That house had been built in 1840 by James Renwick, architect of nearby Grace Church, built in 1845, and St. Patrick’s Cathedral, completed in 1878.) In 1954, the entire block, including the hotel and Mark Twain’s townhouse, was razed to make way for the 19-story Brevoort apartment building. About Lindbergh. As a youth, Lindbergh studied with fascination the flying exploits of the French ace Rene Fonck, who shot down 75 German planes during World War I. In September 1926, Fonck set his sights on claiming Orteig’s prize by crossing the Atlantic from New York to Paris. Fonck’s attempt failed before it ever got off the ground, when his luxurious silver biplane burst into flames on takeoff. Fonck survived the crash, but two crew members were killed. By this time Lindbergh had gained a reputation as a talented barnstormer, although he had not achieved the widespread acclaim of some of his fellow fliers. Nevertheless, his experience as daredevil, mechanic, and intrepid airmail pilot drew the notice of what was then a small 2 community of fliers. Just as important was the fact that Lindbergh had the confidence necessary to undertake such a bold adventure as a transatlantic flight. Lindbergh recalled that confidence in his autobiography, the Spirit of St. Louis: “Why shouldn’t I fly from New York to Paris? ...I have more than four years of aviation behind me, and close to 2,000 hours in the air. I’ve barnstormed over half of the 48 states…. Why am I not qualified for such a flight? Convinced that he was qualified for such a flight, Lindbergh set out to convince others too. He found his partners in February 1927. Less than 24 hours after hearing of Lindbergh’s search for a single-engine plane for such a flight, the Ryan Airlines Corporation, of San Diego, offered to build such a craft. About the Spirit of St. Louis. The airplane that Lindbergh would fly, dubbed the Spirit of St. Louis, was designed and built with the single goal of a transatlantic flight. Compared to a typical plane, extra fuel tanks were added and its wing span increased to accommodate the additional weight. The plane would have a maximum range of 4,000 miles, more than enough to reach Paris from New York. One innovative design decision put the main fuel tank in front of the pilot, rather than behind. Lindbergh didn’t want to be caught between the tank and the engine if the plane was forced into an emergency landing. This configuration meant that Lindbergh would not be able to see directly ahead as he flew. That did not seem to trouble him much, as he later wrote: “There’s not much need to see ahead in normal flight. I won’t be following any airways. When I’m near a flying field, I can watch the 3 sky ahead by making shallow banks. All I need is a window on each side to see through.” If he needed to see ahead, Lindbergh would use a periscope attached to the plane’s port side. The plane’s overall weight was crucial, so every ounce mattered. In his efforts to pare down the plane’s weight, Lindbergh considered every detail. He left behind any item considered too heavy or unnecessary, including a radio, parachute, gas gauges, and navigation lights. He designed special, lightweight boots for the flight and went so far as to cut his maps down to include only the reference points that he would need. Instead of a heavy leather pilot’s seat, Lindbergh would perch on a far lighter wicker chair. Once the plane was built and flight-ready, the plan was that Lindbergh would fly it from the Ryan factory in San Diego to an airfield in New York. Upon its completion on April 28, 1927, the Spirit of St. Louis weighed in empty at 2,150 pounds. Still on view at the Smithsonian Museum of Air and Space, the plane stands nine feet, eight inches high, and extends 27 feet, eight inches in length, with a wingspan of 46 feet. The craft was powered by a 220-horsepower, air cooled, nine-cylinder Wright J-5C “Whirlwind” engine that was designed to perform flawlessly for over 9,000 hours. This engine was outfitted with a special mechanism designed to keep it lubricated during the entire transatlantic flight. Disaster. Two days before Lindbergh’s scheduled departure from San Diego on May 10, 1927, the news broke that the French pilots Charles Nungesser and Francois Coli had taken off from Paris bound for New York. It appeared as though all of Lindbergh’s and Ryan Airline’s efforts 4 would be in vain. Despite a radio report claiming that Nungesser and Coli had been spotted over the Atlantic, the two were never heard from again. Thus, the loss of Nungesser and Coli meant that Lindbergh’s chance for glory was still within reach. “Lucky Lindy” and the Spirit of St. Louis landed at Curtis Field on Long Island (New York) on May 12, 1927. En route, pilot and plane set a new record for the fastest United States transcontinental flight. Eight days later, Lindbergh took off for Paris from New York’s Roosevelt Field. Fighting fog, icing, and sleep deprivation, Lindbergh landed safely at Le Bourget Field in Paris at 10:22 PM on May 20, 1927 – and a new aviation hero was born. The plane had carried him over 3,600 miles in under 34 hours. Boom. The first trans-Atlantic flight heralded the “Lindbergh Boom” in aviation. Aircraft industry stocks rose in value, and interest in flying skyrocketed. Lindbergh’s subsequent U.S. tour in the Spirit of St. Louis demonstrated the potential of the airplane as a safe, reliable mode of transportation. Following his U.S. tour, Lindbergh took his plane on a goodwill flight to Central and South America, where he painted the flags of the nations he visited on the cowling of his plane. 5 Bust. Conversely, Raymond Orteig is all but forgotten. His Lafayette Hotel (known as the Hotel Martin from 1863 to 1902, when Orteig acquired and rechristened it) was patronized by international celebrities who were drawn by its French food and service. When the Brevoort faltered in 1932 during the Great Depression (as did so many other hotels), Orteig sold it and nurtured the Lafayette through the depression. In 1953 the Lafayette was demolished for a modern apartment building, the six-story Lafayette Apartments at University Place and 9th Street. Stanley Turkel, MHS, ISHC, is a New York-based hotel consultant specializing in hotel franchising issues, asset management and litigation support services. He is a member of the International Society of Hospitality Consultants and can be reached at stanturkel@aol.com and 917-628-8549. 6