Charles Lindbergh & the Spirit of St. Louis

advertisement

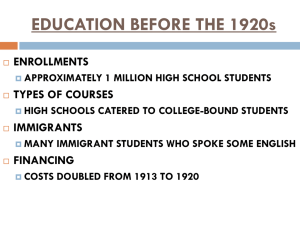

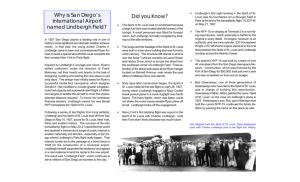

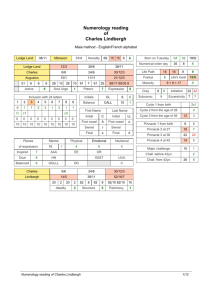

Charles Lindbergh & the Spirit of St. Louis Power point created by Robert Martinez Primary Content Source: A History of US, War, Peace, and All That Jazz; by Joy Hakim In 1919, a wealthy hotel man, Raymond Orteig, offered a prize of $25,000 to anyone who could fly from New York to Paris. Several pilots tried for the prize. No one collected. In 1927, competition got fierce. Besides the money, everyone knew there would be much glory for the pilot who first crossed the Atlantic Ocean. In April, Richard E. Byrd took off, crashed, and broke his wrist. That same April, two pilots set out from Virginia, crashed, and were killed. In early May, two French aces left Paris, headed out over the Atlantic, and were never heard of again. In mid-May, three planes were being made ready. Newspapers were full of their stories. The competition had captured the imagination of people on both sides of the Atlantic. Most of the newspaper attention focused on Byrd, who was famous and eager to try again. His plane had three engines and a well-trained crew. The second plane, with two engines, was to be flown by two experienced pilots. The third plane, a small singleengine craft, could hold only one person. It was called the Spirit of St. Louis. The Spirit of St. Louis got its name, from a group of St. Louis businessmen who helped pay for the plane. The pilot, Charles Lindbergh, was little known. He’d been a barnstormer, a pilot who went around doing trick flying, circles and loops and daredevil things. Lindbergh would take people on plane rides for $5 a spin. Charles Lindbergh picture on left. That was the kind of thing most pilots did in those days. People didn’t use airplanes for transportation. Trains were used to get places. Airplanes? No one was quite sure where the future of aviation lay. But if planes could fly across the ocean safely, they might have an important future. Lindbergh was a good pilot. He was the first man to fly the U.S. mail from St. Louis to Chicago. And the first to survive four forced parachute jumps (forced because his planes developed problems and crashed.) Something about him attracted people. Partly it was his looks. He was tall, six-foot-two, thin, with light, curly hair and a boyish grin. He looked younger than his 25 years. He was quiet, and was always more at ease with machines, or nature, than with people. He’d grown up in Minnesota, where his father was a congressman. Lindbergh never did well in school, maybe because he went to a different school almost every year. But he was smart enough to do a lot of reading. It was 8 a.m. on May 20 when he took off. The weather wasn’t good, but he was anxious to beat the others, and he was used to flying the mail in all kinds of weather. His little plane carried so much gasoline that some people thought it would never get into the air. But Lindbergh had planned carefully. There wasn’t an extra ounce on the plane. He sat in a light wicker chair and carried little besides the fuel, a quart of water, a paper sack full of sandwiches, and a rubber raft. There was no parachute, it would be of no use over the ocean, and there was no radio. He would be on his own once he left the East Coast. Lindbergh headed out to sea, and people around the world learned of it on their radios. That evening, during a boxing match at Yankee Stadium, the spectators rose and said a prayer for Charles Lindbergh, somewhere over the Atlantic Ocean. Lindbergh had to stay awake or crash. After eight or ten hours of sitting in one place he began to doze. The night before the flight he had been so excited, that he had not slept at all. Luckily the plane was frail. It banged about in the wind, and each time he started to nod it went spiraling down toward the water. That woke him. Then miraculously, the fatigue ended, he looked down, and there was Ireland. Lindbergh was exactly where the charts said he should be. Cockpit of the Spirit of St. Louis. Lindbergh didn’t know that his plane was spotted over Ireland and the news radioed to America and France. People cheered and wept with relief. He was seen over London, and then over the English Channel. Thirty-three and a half hours after he left the United States, he circled the Eiffel Tower in Paris. It had taken less time than he expected, so he was worried that no one would be at the airport to meet him. Then he looked down and saw a mob of people. They were waving and screaming. The young flyer, who had brought nothing with him but the paper bag with sandwiches, was carried about on shoulders and hugged and kissed and cheered. Charles Lindbergh was soon meeting kings and princes and more crowds of admirers. He wanted to stay in Europe and see the sights, but President Calvin Coolidge sent a naval cruiser to Europe just to carry him and the Spirit of St. Louis back to America. He was a world hero. Charles Lindbergh & President Calvin Coolidge. All over America there were parades and dinners and celebrations for the man they called “Lone Eagle.” People went wild with pride and excitement. By the way, Lindbergh collected the prize check.