About To Kill a Mockingbird

advertisement

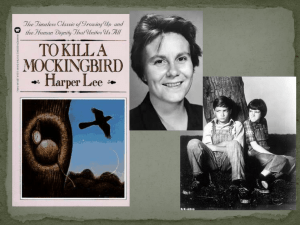

To Kill a Mockingbird

You never really understand a person until you consider things from his point of view--until you climb inside of his skin

and walk around in it.

Biography:

Nelle Harper Lee

Nelle Harper Lee was born on April 28 1926 in Monroeville Alabama, a city of

about 7,000 people in Monroe County, which has about 24,000 people.

Monroeville is in southwest Alabama, about halfway between Montgomery and

Mobile.

She is the youngest of four children of Amasa Coleman Lee and Frances Finch

Lee. Harper Lee attended Huntingdon College 1944-45, studied law at University

of Alabama 1945-49, and studied one year at Oxford University. In the 1950s she

worked as a reservation clerk with Eastern Air Lines and BOAC in New York

City.

In order to concentrate on writing Harper Lee gave up her position with the

airline and moved into a cold-water apartment with makeshift furniture. Her

father's sudden illness forced her to divide her time between New York and

Monroeville, a practice she has continued.

In 1957 Miss Lee submitted the manuscript of her novel to the J. B. Lippincott

Company. She was told that her novel consisted of a series of short stories strung together, and she was

urged to re-write it. For the next two and a half years she re-worked the manuscript with the help of her

editor, Tay Hohoff, and in 1960 To Kill a Mockingbird was published, her only published book. On May 29

1961 the Alabama Legislature passed a resolution to congratulate Miss Lee on her success. That year she

had two articles published: Love--In Other Words in Vogue, and Christmas To Me in McCalls. "Christmas

To Me" is the story of Harper Lee receiving the gift of a year's time for writing from friends. When

Children Discover America was published in 1965.

In June of 1966, Harper Lee was one of two persons named by President Johnson to the National Council

of Arts. Also named to the 26 member council was artist Richard Diebenkorn Jr.

In the same year, on November 28th, Truman Capote held his fabulous and flawless Black and White

Dance in honour of Katherine Graham. In Cold Blood had been published in January, with its dedication to

Jack Dunphy and Harper Lee. The 480 invitations included one to her.

Miss Lee attended the 1983 Alabama History and Heritage Festival in Eufaula, Alabama. She presented the

essay Romance and High Adventure. Most of what has been published on the doings of Miss Lee in the last

many years is speculation. Apparently she still plays golf, and there are various stories of her writing her

memoirs. An article in the Standard Times reported that Miss Lee was working on a book about the

Reverend Maxwell of Alexander City, Alabama. He was a local black preacher who murdered several

family members in order to collect their life insurance, and who was murdered at the funeral of his last

victim.

In his book Lost Friendships Donald Windham reported that in 1984 Miss Lee attended a dinner at his

place after the memorial for Truman Capote. She came with Alvin and Marie Dewey, who she had met

when in Kansas with Capote to do research for In Cold Blood.

Windham cooked chicken breasts in butter. He reported that Miss said that it had been fifteen years since

she and Capote had been in touch.

Miss Lee has received a number of honorary doctorates, perhaps four. In 1990 she was one of five

recipients at the University of Alabama. She did not speak or give an interview.

In 1997 she was awarded an honorary doctorate of humane letters at Spring Hill College in Mobile

Alabama. Professor Margaret Davis told Miss Lee she was being honored for her "lyrical elegance, her

portrayal of human strength, and wisdom." Miss Lee did not speak to the cheering and applauding

audience; Colman McCarthy, another degree recipient did. A photograph of a radiant Miss Lee appeared in

the Mobile Register on May 12, 1997.

About To Kill a Mockingbird

Harper Lee wrote To Kill a Mockingbird during a very tense time racially in her home state of

Alabama. The South was still segregated, forcing blacks to use separate facilities apart from those used by

whites, in almost every aspect of society. The Civil Rights Movement began to pick up steam when Rosa

Parks refused to give up her seat on a bus in Montgomery, Alabama, in 1955. Following her bold defiance,

Marin Luther King, Jr., became the leader of the movement, and the issue began to gain serious national

attention. Clearly, a prime subject of To Kill a Mockingbird, namely the injustice of racism and inequality

in the American South, was highly relevant at the time of its publication.

Interestingly, Harper Lee decided to set the novel in the Depression era of the 1930s. The main

character, Scout, is based on Lee's own childhood, and Dill is most likely based on her childhood friend and

neighbor, Truman Capote. By placing her novel in the 1930s, Lee provided her readers with a historical

background for current events of the time, and in doing so she exposed the deeply rooted history of the civil

rights struggle in the South.

In addition to a biting analysis of race relations, To Kill A Mockingbird is also a story about

Scout's maturation. Coming-of-age stories are also known as members of the genre Bildungsroman, a

novel about the early years of somebody's life, exploring the development of his or her character and

personality, which tends to depict main characters who take large steps in personal growth due to life

lessons or specific trauma. In the novel, this is also true for Boo Radley and by metaphor, the town as a

whole, but it centralizes around the character of Scout. In Lee's novel, Scout Finch works to come to terms

with the facts of her society, including social inequality, racial inequality, and the expectation that she act

as a "proper Southern lady." Scout is a tomboy who resents efforts to alter her behavior in order to make

her more socially accepted. In the 1930s, gender inequality also reigned, and women were not given equal

rights. Women in the South were expected to be delicate and dainty, concepts that Scout abhors; and

women were not allowed to serve on juries in Maycomb, according to the novel. Scout loves adventure and

can punch as well as any boy in her class. She finds it hard to fit into the mold of a Southern lady. Miss

Maudie is a strong role model for her in that Miss Maudie also defies some of their society's expectations

and maintains her individuality as a Southern woman. But Scout eventually succumbs--in her own way--to

social pressure.

The novel's characters are forced to examine the world (or at least the town) in which they live.

Through observing their society and interacting with people such as Tom Robinson and Boo Radley, they

come to understand more about true bravery, cowardice, and humanity.

Theme Develeopment:

When Children Discover America by Harper Lee

Wordsworth was right when he said that we trail clouds of glory as we come into the world, that we are

born with a divine sense of perception. As we grow older, the world closes in on us, and we gradually lose

the freshness of viewpoint that we had as chi ldren. That is why I think children should get to know this

country while they are young.

I do not think the youngest or even the most jaded citizen could go to Washington and through the Capitol

or the Smithsonian Institution without having the feeling of yes, we are something; yes, we do have a

history. It may be a short one, but every bit of it has worked to make us what we are, and it's there to be felt

in Washington.

I would like to take children to the South, perhaps to Charleston, a small city of great character and great

historic interest--a seaport town with a distinct air of something that was. In the Far West, I would show

children San Francisco. The Chinese people there are such wonderful Americans. They are people with

their own ancient culture, and yet they have become part of our civilization. New England, of course--in

autumn, you can get drunk on maple trees. And that first sight of the Rockies from the plains in Colorado.

You go through miles and miles of flatland country--and then suddenly, there they are, snow-capped in all

their majesty. Oceans and beaches-the Gulf side of Florida, down around Naples and Sarasota, with green,

green water. And my own part of home--pine-forest country, dense and beautiful.

I would like to show children my own town, my own street, my own neighbors. I live on the corner. My

next-door neighbor is a barber, and his wife owns a dress shop. My down-the-street neighbor has a grocery

store, and my neighbor down the hill is a teacher. My neighbor to the rear is a doctor; behind him is a

druggist. If children were visiting--from abroad or from other parts of the country--they would have

cookies and ice cream for them, and take them to the park with the lake and the swimming pool, and my

cook, Mary, would make them an enormous cake covered with caramel frosting, and for dinner give them

fresh vegetables from the garden and Southern chicken cooked right.

And then we would let them alone, to explore on there own. It's stifling to have adults with you all the time

when you are a child, to tell you about everything and explain things away for you. There is no sense of

discovery for a young, exploring spirit when adults are with you all the time to give absolutely straight

answers to everything.

I don't think, for instance, that the Lincoln Memorial needs to be pointed out to any human being of any

age. I would let children discover the beauty and mystery and grandeur of it. They'll ask questions later. No

child can possibly leave the Lincoln Memorial without questions, often important questions.

If more young people traveled with their eyes and minds open and saw this country, they would have a

deeper feeling about it. Adventuring across the country is out of style. Whatever happened to working after

school in a grocery store to get enough money to hitchhike to California during your vacation? My

youngest nephew may be one of the last to do that, and he did it when he was fifteen. His parents were

terrified, but he got himself to the World's Fair. His mother had thoughtfully sewn a bus ticket into the cuff

of his trousers, but he swore he would never use it. He ended up in Chicago and lived on milk and rolls for

three days because he didn't have any money. When he finally got home, he had lost thirty pounds; but he

was the happiest boy I had ever seen in my life. He had discovered America for himself. It

will mean something to him for the rest of his life.

Younger children may not respond in words, but they will drink everything in with their eyes, and fill their

minds with awareness and wonder. It's an experience they will enjoy and remember all their lives; and it

will give them greater pride in their own country.

Personal knowledge of his own country is part of every American's heritage, as Pulitzer Prizewinning author Harper Lee says [above].

To help us see our country through fresh eyes, we followed the adventures of a small French girl, her brother and her parents, as they

visited the United States for the first time in their lives. We photographed their reactions to the places they saw and the welcome they

received from ordinary citizens and outstanding Americans, including Vice-President Hubert H. Humphrey, opposite page. What ever

your nationality, we feel that it's a good year to discover America the beautiful, the friendly, the inspiring. --The Editors

"When Children Discover America" was published in McCalls August 1965.

Historical Analysis:

The Scottsboro Trial

Tom Robinson's trial bears striking parallels to the "Scottsboro Trial," one of the most famous-or infamouscourt cases in American history. Both the fictional and the historical cases take place in the 1930s, a time of

turmoil and change in America, and both occur in Alabama. In both, too, the defendants were AfricanAmerican men, the accusers white women. In both instances the charge was rape. In addition, other

substantial similarities between the fictional and historical trials become apparent.

A study of the Scottsboro trials will sharpen the reader's understanding of To Kill a Mockingbird. Both the

historical trial(s) and the fictional one reflect the prevailing attitudes of the time, and the novel explores the

social and legal problems that arise because of those attitudes.

First, it is essential to understand the social and economic climate of the 1930s. The country was in what

has been called the Great Depression. Millions of people had lost their jobs, their homes, their businesses,

or their land, and everything that made up their way of life. In every American city of any size, long "bread

lines" of the unemployed formed to receive basic foodstuffs for themselves and their families, their only

means of subsistence.

Many people lived in shanty towns, their shelters made of sheet metal and scrap lumber lean-tos. All over

America it was common to see unemployed men and women riding the rails, looking for work, shelter, and

food-for anything that offered some means of subsistence, some sense of dignity. It was a time when even a

full-time employee, such as a mill worker, earned barely enough to live on. In fact, in 1931 a person

working 55 or 60 hours a week in Alabama and other places would earn only about $156 annually.

The economic collapse of the 1930s resulted in ferocious rivalry for the very few jobs that became

available. Consequently, the ill will between black and white people (which had existed ever since the Civil

War) intensified, as each group competed with the other for the few available jobs. One result was that

incidents of lynchings--primarily of African-Americans--continued. Here, lynching should be defined as

the murder of a person by a group of people who set themselves up as judge, jury, and executioner outside

the legal system.

It was in such a distressing social and economic climate that the Scottsboro case (and Tom Robinson's case)

unfolded.

On March 25, 1931, several groups of white and black men and two white women were riding the rails

from Tennessee to Alabama in various open and closed railroad cars designed to carry freight and gravel.

At one point on the trip, the black and white men began fighting. One white man would later testify that the

African-Americans started the fight, and another white man would later claim that the white men had

started the fight. In any case, most of the white men were thrown off the train. When the train arrived at

Paint Rock, Alabama, all those riding the rails-including nine black men, at least one white man, and the

two white women--were arrested, probably on charges of vagrancy. The white women remained under

arrest in jail for several days, pending charges of vagrancy and possible violation of the Mann Act. The

Mann Act prohibited the taking of a minor across state lines for immoral purposes, like prostitution.

Because Victoria Price was a known prostitute, the police were tipped off (very likely by the mother of the

underaged Ruby Bates) that the two women were involved in a criminal act when they left Tennessee for

Alabama. Upon leaving the train, the two women immediately accused the African-American men of

raping them in an open railroad car (referred to as a "gondola") that was carrying gravel (or, as it was

called, "chert").

The trial of the nine men began on April 6, 1931, only twelve days after the arrest, and continued through

April 9, 1931. The chief witnesses included the two women accusers, one white man who had remained on

the train and corroborated their accusations, another acquaintance of the women who refused to corroborate

their accusations, the physician who examined the women, and the accused nine black men. The accused

claimed that they had not even been in the same car with the women, and the defense attorneys also argued

that one of the accused was blind and another too sickly to walk unassisted and thus could not have

committed such a violent crime. On April 9, 1931, eight of the nine were sentenced to death; a mistrial was

declared for the ninth because of his youth. The executions were suspended pending court appeals, which

eventually reached the Supreme Court of the United States.

On November 7, 1932, the United States Supreme Court ordered new trials for the Scottsboro defendants

because they had not had adequate legal representation.

On March 27, 1933, the new trials ordered by the Court began in Decatur, Alabama, with the involvement

of two distinguished trial participants: a famous New York City defense lawyer named Samuel S.

Leibowitz, who would continue to be a major figure in the various Scottsboro negotiations for more than a

decade; and judge James E. Horton, who would fly in the face of community sentiment by the unusual

actions he took in the summer of 1933.

In this second attempt to resolve the case, the trial for the first defendant lasted almost two weeks instead of

only a few hours, as it had in 1931. And this time the chief testimony included the carefully examined

report of two physicians, whose examination of the women within two hours of the alleged crime refuted

the likelihood that multiple rapes had occurred. Testimony was also given by one of the women, Ruby

Bates, who now openly denied that she or her friend, Victoria Price, had ever been raped. As a result of

this, as well as of material brought out by investigations and by cross-examinations of the witnesses of

Samuel Leibowitz, the character and honesty of accuser Victoria Price came under more careful scrutiny.

On April 9, 1933, the first of the defendants, Haywood Patterson, was again found guilty of rape and

sentenced to execution. The execution was delayed, however; and six days after the original date set for

Patterson's execution, one of the most startling events of the trial took place: local judge James Horton

effectively overturned the conviction of the jury and, in a meticulous analysis of the evidence that had been

presented, ordered a new trial on the grounds that the evidence presented did not warrant conviction. (It is

probably not a coincidence that Judge Horton lost an election in the fall following his reversal of the jury's

verdict.)

Despite judge Horton's unprecedented action, the second defendant, Clarence Norris, was tried in late 1933

and was found guilty as charged; but his execution was delayed pending appeal.

During this time all the defendants remained in prison, and not for two more years was any further

significant action taken as Attorney Leibowitz filed appeals to higher courts. Finally, on April 1, 1935, the

United States Supreme Court reversed the convictions of Patterson and Norris on the grounds that qualified

African-Americans had been systematically excluded from all juries in Alabama, and that they had been

specifically excluded in this case.

However, even this decision by the Supreme Court was not the end of the trials, for on May 1, 1935,

Victoria Price swore out new warrants against the nine men.

Primary documents related to the case afford several avenues of comparison between the Scottsboro trials

and Tom Robinson's trial in To Kill a Mockingbird. This is in addition to the more obvious parallels of time

(1930s), place (Alabama), and charges (rape of white women by African-American men). First, the threat

of lynching is common to both cases. Second, there is a similarity between the novel's Atticus Finch and

the real-life judge James E. Horton, both of whom acted in behalf of black men on trial in defiance of their

communities' wishes at a time of high feeling. In several instances, the words of the Alabama judge remind

the reader of Atticus Finch's address to the jury and his advice to his children. Third, the accusers in both

instances were very poor, working-class women who had secrets that the charges of rape were intended to

cover up. Therefore, the veracity or believability of the accusers in both cases became an issue.

THE TESTIMONY OF VICTORIA PRICE AND DR. R. R. BRIDGES, APRIL 3, 1933, AS

REPORTED IN THE NEW YORK TIMES

New York Times, Tuesday, April 4, 1933, p. 10, Vol. LXMI.

The retrial of Haywood Patterson got under way in early April, shortly after the choosing of the jury and

the address of Judge Horton to the courtroom. This document is from a New York Times account of the

testimony given on April 3. The star witnesses on this day were the chief accuser, Victoria Price, and Dr. R.

R. Bridges, who had given her a physical examination within two hours of the alleged rape. Both witnesses

had testified in the 1931 trial, but in April 1933 attention is called to Victoria Price's character and the

contradictions in her testimony, giving rise to questions about her truthfulness. Furthermore, as this

document illustrates, the testimony of Dr. Bridges for the first time is under serious scrutiny, not only from

the defense attorney but from the presiding judge.

GIRL REPEATS STORY IN SCOTTSBORO CASE.

MORAL ATTACK RULED OUT: Judge Rejects Court Records as Not Affecting the Credibility of Her Testimony

State's Witness at Decatur Trial Screams Denial of "Framing" Negro Defendants By RAYMOND F.

DANIELL, Special to the New York Times. DECATUR, Ala., April 3.

Victoria Price, whose testimony two years ago at Scottsboro led Jackson County juries to condemn eight of

nine negro defendants to death, repeated her charges today before Judge James E. Horton and a jury in the

Morgan County Court House at the first of the retrials ordered by the United States Supreme Court.

At times when Samuel S. Leibowitz, chief of defense counsel, pressed searching questions regarding her

past, her lip curled and she snapped her answers in the colloquialisms of the "poor white."

Mrs. Price entered an angry denial when Mr. Leibowitz asked if she had not concocted the whole story of

the mass attack by the negroes and forced Ruby Bates, the other victim of the alleged crime, to corroborate

her in order to forestall the danger of her own arrest for vagrancy or a more serious offense....

SHOUTS ANSWERS TO QUESTIONS

"That's some of that Ruby Bates' dope," she shouted in a voice that shook with anger.

"You can't prove it," she shouted another time when Mr. Leibowitz promised to show the court that the

condition in which doctors found her when she was examined at Scottsboro after an armed posse had taken

the girls and the negroes off the train on which the attack supposedly took place, was the result of her

misconduct the night before in a hobo jungle on the outskirts of Chattanooga.

Certified copies of court records from Huntsville where Mrs. Price lived with her widowed mother were

offered by Mr. Leibowitz to show that prior to March 25, 1931, she had been arrested for offenses against

the moral code.

She defended the testimony she had given with as much fire as she defended her reputation, heatedly

denying at one moment that she had wrecked the home of a married woman with two babies, and in the

next breath thrusting aside seeming inconsistencies in her testimony with apologies for her lack of

education and faulty memory.

DOCTOR DESCRIBES INJURIES

Although Mrs. Price insisted that she had fought the negroes until her strength gave out, and declared that

her head was cut open by a blow from the of a pistol wielded by Patterson, Dr. R. R. Bridges, the

Scottsboro physician, who testified just before adjournment, said he had found only superficial bruises and

scratches when he examined her.

While the doctor was on the stand judge Horton took a hand in the examination, showing particular interest

in the physician's statement that neither Mrs. Price nor her companion, the Bates girl, were hysterical or

nervous when they were brought to his office. Not until the next day, he said, did either of them show any

signs of nervousness and then, after a night in jail, it manifested itself in tears.

The star witness for the State told the sordid details of the crime before a crowded court with unabashed

frankness and plain-speaking. She repeated the lewd remarks she said the negroes made to her without the

flutter of an eyelash and in a voice that carried to the furthest comer of the courtroom. The only women in

the crowd which heard her story and the very clinical medical testimony which followed were two visitors

from New York. At times they looked as though they wished they had not come.

Metaphorical Analysis:

Countee Cullen:

"... in spite of myself, I find that I am actuated by a strong sense of race consciousness. This grows upon me."

Incident

Once riding in old Baltimore,

Heart-filled, head-filled with glee;

I saw a Baltimorean

Keep looking straight at me.

Now I was eight and very small,

And he was no whit bigger,

And so I smiled, but he poked out

His tongue, and called me, "Nigger."

I saw the whole of Balimore

From May until December;

Of all the things that happened there

That's all that I remember.

Countee Cullen: American poet, a leading figure with Langston Hughes in the Harlem Renaissance.

This 1920s artistic movement produced the first large body of work in the United States written by African

Americans. However, Cullen considered poetry raceless, although his 'The Black Christ' took a racial

theme, lynching of a black youth for a crime he did not commit.

Yet Do I Marvel

I doubt not God is good, well-meaning, kind,

And did He stoop to quibble could tell why

The little buried mole continues blind,

Why flesh that mirrors Him must someday die,

Make plain the reason tortured Tantalus

Is baited by the fickle fruit, declare

If merely brute caprice dooms Sisyphus

To struggle up a never-ending stair.

Inscrutable His ways are, and immune

To catechism by a mind too strewn

With petty cares to slightly understand

What awful brains compels His awful hand.

Yet do I marvel at this curious thing:

To make a poet black, and bid him sing!

Countee Cullen was very secretive about his life. According to different sources, he was born in Louisville,

Kentucy or Baltimore, Md. Cullen was possibly abandoned by his mother, and reared by a woman named

Mrs. Porter, who was probably his paternal grandmother. Cullen once said that he was born in New York

City - perhaps he did not mean it literally. Porter brought young Countee to Harlem when he was nine. She

died in 1918. At the age of 15, Cullen was adopted unofficially by the Reverend F.A. Cullen, minister of

Salem M.E. Church, one of the largest congregations of Harlem. Later Reverend Cullen became the head of

the Harlem chapter of NAACP.

Cullen won a citywide poetry contest and saw his winning stanzas widely reprinted. With the help of

Reverend Cullen, he attended the prestigious De Witt Clinton High School in Manhattan. After graduating,

he entered New York University, where his works attracted critical attention.

Cullen's first collection of poems, COLOR (1925), was published in the same year he graduated from

NYU. Written in a careful, traditional style, the work celebrated black beauty and deplored the effects of

racism. The book included 'Heritage' and 'Incident', probably his most famous poems. 'Yet Do I Marvel',

about racial identity and injustice, showed the influence of the literary expression of William Wordsworth

and William Blake, but its subject was far from the world of their Romantic sonnets. The poet accepts that

there is God, and 'God is good, well-meaning, kind', but he finds a contradiction of his own plight in a

racist society: he is black and a poet.

The Loss of Love

All through an empty place I go,

And find her not in any room;

The candles and the lamps I light

Go down before a wind of gloom.

Thick-spraddled lies the dust about,

A fit, sad place to write her name

Or draw her face the way she looked

That legendary night she came.

The old house crumbles bit by bit;

Each day I hear the ominous thud

That says another rent is there

For winds to pierce and storms to flood.

My orchards groan and sag with fruit;

Where, Indian-wise, the bees go round;

I let it rot upon the bough;

I eat what falls upon the ground.

The heavy cows go laboring

In agony with clotted teats;

My hands are slack; my blood is cold;

I marvel that my heart still beats.

I have no will to weep or sing,

No least desire to pray or curse;

The loss of love is a terrible thing;

They lie who say that death is worse.

Cullen's Color was a landmark of the Harlem Renaissance. The movement was centered in the

cosmopolitan community of Harlem, in New York City. During the 1920s, a fresh generation of writers

emerged, although a few were Harlem-born. Among the leading figures were Alain Locke (The New

Negro, 1925), James Weldon Johnson (Black Manhattan, 1930), Claude McKay (Home to Harlem, 1928),

Langston Hughes (The Weary Blues, 1926), Zora Neale Hurston (Jonah's Gourd Vine, 1934), Wallace

Thurman (Harlem: A Melodrama of Negro Life, 1929), Jean Toomer (Cane, 1923), Arna Bontemps (Black

Thunder, 1935), and of course Countee Cullen, a leading voice of the period. - The movement was

accelerated by grants and scholarships and supported by such white writers as Carl Van Vechten.

A brilliant student, Cullen graduated from New York University Phi Beta Kappa. He attended Harvard,

earning his masters degree in 1926. He worked as assistant editor for Opportunity magazine, where his

column, 'The Dark Tower,' increased his literary reputation. Cullen's poetry collections THE BALLAD OF

THE BROWN GIRL (1927) and COPPER SUN (1927) explored similar themes as Colour, but they were

not so well received. Cullen's Guggenheim Fellowship of 1928 enabled him to study and write abroad. He

married in April 1928 Nina Yolande Du Bois, daughter of W.E.B. DuBois, the leading black intellectual.

At that time Yolande was involved romantically with a popular band leader. Between the years 1928 and

1934, Cullen travelled back and forth between France and the United States.

By 1929 Cullen had published four volumes of poetry. The title poem of THE BLACK CHRIST AND

OTHER POEMS (1929) was criticized for the use of Christian religious imagery - Cullen compared the

lynching of a black man to Christ's crucification. His marriage did not succeed and he divorced in 1930.

Extra load for the marriage was Cullen's and Harold Jackman's close friendship. Jackman was a a teacher

whom the writer Carl Van Vechten had used as model in his novel Nigger Heaven (1926). In 1940 Cullen

married Ida Mae Robertson; they had known each other for ten years.

As well as writing books himself, Cullen promoted the work of other black writers. Cullen also translated

the Greek tragedy Medea by Euripides, which was published in THE MEDEA AND SOME POEMS

(1935), with a collection of sonnets and short lyrics.

As a poet Cullen was conservative: he did not ignore racial themes, but based his works on the Romantic

poets, especially Keats, and often used the traditional sonnet form. "Not writ in water nor in mist, / Sweet

lyric throat, thy name. / Thy singing lips that cold death kissed / Have seared his own with flame." ('2. For

John Keats, Apostle of Beauty') However, Cullen also enjoyed Langston Hughes's black jazz rhythms, but

more he loved "the measured line and the skillful rhyme" of the 19th century poetry. After the early 1930s

Cullen avoided racial themes. Cullen's later publications include ON THESE I STAND (1947), a collection

of his favorite poems, and the play THE THIRD FOURTH OF JULY (publ. 1946). Cullen died of uremic

poisoning in New York City on January 9, 1946. Private about his life, he left behind no autobiography.

Saturday's Child

Some are teethed on a silver spoon,

With the stars strung for a rattle;

I cut my teeth as the black racoon-For implements of battle.

Some are swaddled in silk and down,

And heralded by a star;

They swathed my limbs in a sackcloth gown

On a night that was black as tar.

For some, godfather and goddame

The opulent fairies be;

Dame Poverty gave me my name,

And Pain godfathered me.

For I was born on Saturday-"Bad time for planting a seed,"

Was all my father had to say,

And, "One mouth more to feed."

Death cut the strings that gave me life,

And handed me to Sorrow,

The only kind of middle wife

My folks could beg or borrow.