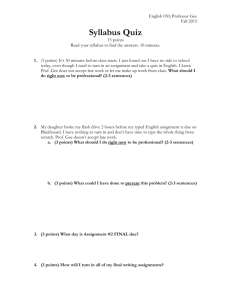

Context-Embedded Learning (LONG)

advertisement

Perhaps the most fundamental property of a constructivist learning environment is that it offers a context for student learning. Context-embedded learning has been a cornerstone of the constructivist movement since at least the early 1900’s. Now, nearly a century later, video games and simulations can offer new contexts for student learning that would not have been available to students in the past. Video games are able to provide students with a context that allows them to learn by doing, remain in a state of flow, explore microworlds that allow easy transfer of learning, develop situated and distributed understanding, exercise new identities, and benefit from role-playing. Learning By Doing While traditional teaching and learning tends to be a passive experience for the student who receives knowledge from the teacher, constructivist pedagogy emphases learning by doing, learning from experience, and problem solving in context. In order to learn by doing, a student must not simply read from a textbook or listen to a lecture. Rather, the student must engage authentic (or real-world) problems in their authentic context. Dewey (1915), for instance, felt that school work was “remote and shadowy compared with the training of attention and of judgment that is acquired in having to do things with a real motive behind and a real outcome ahead” (p. 12). He later noted that “one trouble [with traditional education] is that the subject-matter in question was learned in isolation” (1938, p. 48). Dewey (1915) was much more interested in students “having a part to do in constructive work” (p. 17). Consequently, he called for each student to be “given, wherever possible, intellectual responsibility for selecting the materials and instruments that are most fit, and given an opportunity to think out his own model and plan of work, led to perceive his own errors, and find out how to correct them” (p. 133134). He believed that “thinking... arises from the need of meeting some difficulty, in reflecting upon the best way of over coming it, and thus… planning [and] projecting mentally the results to be reached, and deciding upon the steps necessary and their serial order” (p. 135). Bruner (1966), too, urged educators to “consider education and school learning in their situated, cultural context” (p. x). He believed that “in a [traditional] detached school, what is imparted often has little to do with life as lived in the society” (1966, p. 152). He was interested more in history as a discipline than as a curriculum and he believed “it is a lame excuse to say children can’t do it” (Bruner, 1996, p. 91). Invoking Piaget’s little scientist, he also expressed that “learning to be a scientist is not the same as 'learning science': it is learning a culture, with all the attendant 'non-rational' meaning making that goes with it” (Bruner, 1996, p. 132). Ultimately, Bruner was interested in “knowing as doing” (p. 150) and “understanding by doing something other than just taking” (p. 151). Modern video game scholars have argued that video and computer games can help provide such a context for learning. Prensky (2001), for instance, highlighted several relevant concepts; games have rules, goals, outcomes/feedback, conflict/competition/challenge/opposition, problem solving, interaction, representation, and story (p. 106), including character (p. 134, 118-127). Regarding goals specifically, Prensky suggests elsewhere that the goals must be “worthwhile” (2005a, p. 9), or specifically “worth it to [students]” (2005, p. 4), to be effective. When he covers game design, he considers the way in which a game must be balanced so that “the game is neither too hard nor too easy at any point” (Prensky, 2001, p. 133). A well-designed game, particularly an RPG or MMORPG, can also include elements of exploration and discovery as well (p. 136). In his projection of the future of digital games, Prensky (2001) predicts that games will be “much more realistic, experiential, and immersive” and include “more and better storytelling and characters” (p. 404). Prensky later wrote about five levels of learning by doing. The first of these was the How level; as Prensky (2006) explained, “the most explicit kind of learning in video and computer games is how to do something” (p. 64). The second level is learning What to do (and what not to do) in any particular instance (p. 65). The third level of learning is the Why level; “strategy – the why of a game – depends on, and flows from, the rules” (p. 67). Why lessons include cause and effect, long term wining versus short term goals, order from seeming chaos, second-order consequences, complex system behaviors, counter intuitive results, using obstacles as motication, and the value of persistence (p. 67-68). The fourth level, Where “is the context level, which encompasses the huge amount of cultural and environmental learning that goes on in video and computer games” (Prensky, 2006, p. 68). Finally, there is the Whether level, in which “players learn to make value-based and moral decisions – decisions about whether doing something is right or wrong” (p. 69). Like Prensky, Gee discussed ways in which video games can provide a context for learning. Gee (2003), a linguist and cognitive scientist asserted that “words, symbols, images, and artifacts have meanings that are specific to… particular situations (contexts)” (p. 24). He argued that a good game can provide a “context within which to understand and make sense of what one is going to do” (Gee, 2004, p. 64). He also suggested that “the theory of learning in good video games is close to… the best theories of learning in cognitive science” (Gee, 2003, p. 7). Gee (2003) focused on the way that video games can provide a learning environment that is “set up to encourage active and critical, not passive, learning” (p. 49). He believed that active critical learning was based on experiencing (seeing, feeling, and operating on) the world in new ways (p. 23), and on being able to not only “understand and produce meanings” in the domain being learned, but also being able to “think about the domain at a ‘meta’ level as a complex system of interrelated parts” (p. 23). Even at a more basic level, Gee (2003) believed that “basic skills are not learned in isolation or out of context; rather… a basic skill is discovered bottom up by engaging with the domain” (p. 137). Gee also suggested that learners should get “lots of practice in a context where the practice is not boring (i.e. in a virtual world that is compelling to learners on their own terms and where the learners experience ongoing success)” (p. 71). Gee offered the following recipe for providing students with a context for learning. “The recipe is simple: Give people well designed visual and embodied experiences of a domain, through simulations or in reality (or both). Help them use these experience to build simulations in their heads through which they can think about and imaginatively test out future actions and hypotheses. Let them act and experience consequences, but in a protected way when they are learners. Then help hem to evaluate their actions and the consequences of their actions (based on the values and identities they have adopted as participants in the domain) in ways that lead them to build better simulations for better future action. Though this recipe could be a recipe for teaching science in a deep way, it is [also] a recipe for an engaging and fun game. It should be the same in school.” (Gee, 2005, p. 63) Gee (2005a) also expected good games to allow learners to practice skills “until they are nearly automatic, then [to have] those skills fail in ways that cause the learners to have to think again and learn anew” (p. 27) in cycles of expertise. In addition, virtual contexts can provide a greater amplification of input for the learner; in other words, “for a little input, learners get a lot of output” (Gee, 2003, p. 67). Because of these elements, and because of the tireless replayability of a game (as opposed to a teacher who may quickly tire of explaining things more than once), games can offer learners “a context where the practice is not boring” (p. 71) so that “they spend lots of time on task” (p. 71). Learners should also be given “ample opportunity to practice, and support for, transferring what they have learned earlier to later problems, including problems that require adapting and transforming that earlier learning” (p. 138). Aldrich (2005) quotes Will Thalheimer on the role of context in simulations: “The first thing that makes simulations work is context alignment. The performance situation is similar to the learning situation… when the learners enter a real situation, you want the environment to trigger the learning. That results in a 10 to 50 percent learning impact” (Will Thalheimer, as quoted in Aldrich, 2005, p. 84). When Aldrich (2004) discussed the objectives of designing an interface system for a simulation, his most important points were that a simulation interface should “represent the actual activity at some level” (p. 173) and “be a part of the learning” (p. 174) in the sense that simply learning the interface would help a user learn about the subject being learned. Though he advocated for keeping a simulation interface simple and streamlined (p. 175), he was interested in fidelity where it impacted learning. He suggested that a simulation interface should operate in real time such that “all options are available all the time”(p. 175). Similarly, he called for simulation design that, like the real world, included all three types of content, linear, cyclical, and open-ended (p. 99). He also opposed simulations that presented the world as it should be rather than as it is, even if this is done in the name of political correctness (p. 215). Shaffer (2004), too, noted that “new technologies make it easier for students to learn about the world by participating in meaningful activity” (p. 1403). He tied this directly to constructivist tradition, saying that “new technologies support Dewey’s vision of bringing the ‘life of the child’ into an environment for learning” (p. 1404). Shaffer aimed to apply the following philosophy to the design of educational video games: "pedagogical praxis seeks to create environments that are thickly authentic. Resnick and I (Shaffer & Resnick, 1999) argued that authenticity is an alignment between activities and some combination of (a) goals that matter to the community outside of the classroom, (b) goals that are personally meaningful to the student, (c) ways of thinking within an established domain, and (d) the means of assessment. Thickly authentic learning environments create all of these alignments simultaneously. For example, in the case of pedagogical praxis, when personally meaningful projects are produced and assessed according to the epistemological and procedural norms of an external community of practice." (Shaffer, 2004, p. 1406) Shaffer’s epistemic games “are about having students do things that matter in the world by immersing them in rigorous professional practices of innovation” (Shaffer & Gee, 2005, p. 12). As Shaffer and Gee explain, “in this approach, students do things that have meaning to them and to society, supported all along the way by structure, and lots of it—structure that leads to expertise, professional-like skills, and an ability to innovate” (p. 12). They point out that “the key step in developing the epistemic frame of most communities of innovation is in some form of professional practicum… environments in which a learner acts in a supervised setting and then reflects on the results of his or her action with peers and mentors” (p. 14), and they aimed to use video games to provide this practicum. In such epistemic games “students learn facts and content in the context of innovative ways of thinking and working… in a way that sticks, because they learn in the process of doing things that matter” (p. 24). Such epistemic games exemplify the learnby-doing philosophy. In these games, “students were learning to solve real problems by working on real problems, learning how to think about things that matter in the world by actually doing things that matter in the world” (Shaffer, 2006, p. 6). Shaffer (2006) argues that “video games can change education because computers now make it possible to learn on a massive scale by doing the things that people do in the world outside of school” (p. 9). Citing Gee’s principle of performance before competence, Shaffer (2006) explains that with video games students can “learn by doing rather than learning first and doing later” (p. 68), and that the “difference… between declarative knowledge and procedural knowledge, or being able to explain something and being able to actually do it – is fundamental to education as we know it” (p. 92). Again invoking Dewey, Shaffer state that “the process of moving from interest to understanding, according to Dewey, was learning by doing – or, to be more precise, learning by trying to do something, making mistakes, and then figuring out how to fix them” (p. 124). Because epistemic games can “develop professional skills, knowledge, and epistemology in the context of professional values,” Shaffer suggests that, “epistemic games are thus a potentially important part of children’s development” (p. 132). Several other scholars have demonstrated the value of video games in providing a learning context. Like Shaffer, Squire and Jenkins (2003) advocate the use of games “in conjunction with real-world simulations” (p. 9). They also noted that “students learning in the context of solving complex problems not only retain more information but tend to perform better in solving problems” (p. 28). Holland, Jenkins, and Squire (2003) explained that “embedding challenges within the tool requires users to actively monitor their performance, observing, hypothesizing, acting, and reflecting” (p. 37). As they point out, “In addition to being potentially more motivating for learners, engaging in such critical thinking processes is generally thought to be the basis of meaningful learning... knowledge developed in the context of solving problems is typically recalled better than knowledge learned by rote and more readily mobilized for solving problems in novel contexts” (p. 37). Video games that can exercise such thinking processes “give students a sense of the practice for which they’re being trained” (p. 40). McMahan (2003) also discussed the value of the presence and immersion offered by video games (p. 68-77). And, as Filiciak (2003) expressed it, players “desire the experience of immersion, so we use our intelligence to reinforce rather than to question the reality of the experience” (p. 99), a factor that can work both for and against the instructional goals of video games. Flow Ideally, the student in an environment where they can learn by doing will be challenged without being frustrated, and thus remain in a state of flow, an ideal state of learning (or performance). Csikszentmihalyi (1997) described flow experiences as “exceptional moments” (p. 29) that tend to occur “when a person's skills are fully involved in overcoming a challenge that is just about manageable… a fine balance between one's ability to act, and the available opportunities for action” (p. 30). This bears resemblance to Vygotsky’s (1978) Zone of Proximal Development, which also describes the way in which students learn when challenged just beyond the horizon of their mastery, but not so far beyond that they become frustrated. Early in his description of the optimal experiences that generate flow states, Csikszentmihalyi (1997) noted that “it is easy to enter flow in games” (p. 29), at least in part because games, like other flow activities, “provide immediate feedback” (p. 30). Videogames, in particular, are designed to provide individualized levels of challenge and feedback for players. Shaffer (2006) made the connection between video games and Csikszentmihalyi’s work, pointing out that “we learn best when working on things that are neither too easy nor too hard” (p.125). Shaffer went on to point out that, as Dewey suggested “the obstacles have to be relevant to the thing you are trying to do: They have to push back on issues that are related to the task at hand, rather than being something irrelevant or extraneous that you have to overcome in order to keep working” (p. 125). Relevance, which is treated in more detail below, is key to the use of flow experiences for learning – and needs to be present in educational games. Massively multiplayer online roleplaying games (MMORPGs) are a medium in which such relevance might be easily incorporated; as Steinkuehler (2004b) points out, in an MMORGP “information is given ‘just in time,’ always in the context of the goal-driven activity that it’s actually useful for – and made meaningful by – and always at a time when it can be immediately put to use” (p. 7), thus facilitating playing and learning in a state of flow. Microworlds In order to support student’s early efforts, the learning context can be a microworld, or simplified version, of the real-world context in which similar skills might be used – and to which students’ new skills will eventually be expected to transfer. Microworlds model only the elements of the experience that are important to a student’s developmental level, while limiting other distractions. Papert (1980) originated the concept of microworlds as incubators for knowledge (p. 120). This concept of microworlds stems from Papert’s belief “that learning physics consists of bringing physics knowledge into contact with very diverse personal knowledge, [and that] to do this we should allow the learner to construct and work with transitional systems that the physicist may refuse to recognize as physics” (p 122). Microworlds, then, can be considered simply “transitional systems.” Papert explores a set of criteria for creating microworlds. The first of these is that the design should be very simple and accessible (p. 126). It must also offer the “possibility of activities, games, art, and so on… to make the activity in microworlds matter” (p. 126). Finally, microworlds should be designed such that “all needed concepts can be defined within the experience of that world” (p. 126). Later, Papert (1993) explained a Microworlds as “simple, restricted worlds” (p. 56) that are “limited enough to be thoroughly explored and completely understood” (p. 59). “In an analogy between ideas and people,” he explained that “microworlds are the worlds of people we know intimately and well” (p. 59). Jonassen (2000) described microworlds as “primarily exploratory environments, discovery spaces, and constrained simulations of real-world phenomena in which learners can navigate, manipulate or create objects, and test their effects on one another” (p. 157). He also made the observation that “video-based adventure games are microworlds that require players to master each environment before moving onto more complex environments” (p. 157). In Jonassen’s description, a well-designed microworld is one in which “instruction proceeds from simple to complex skills” (p. 159), and the environment exploits “the interest and curiosity of the learner” (p. 159). Microworlds should also be “simple, so they can be understood, general, so they apply to many areas of life, useful, so the ideas are important to learners in the world, and syntonic (resonant with one’s experience), so learners can relate them to prior experience” (p. 159). These elements may be what some games lack, and making these judgments will be one of the challenges of creating good educational games or simulations to serve as microworlds. The goal of a microworld, according to Papert (1980), is to help students “get a feel for why the world works as it does” rather than “to establish a given truth” as the goal would be in traditional pedagogy (p. 129). Papert points out that “we learned how to build and use theories only because we were allowed to hold ‘deviant’ views… for many years” (p. 132). In microworlds, unlike in most schools, false theories are tolerated (p. 132). Learning in microworlds is also product-oriented, such that the child is learning new concepts “as a means to get to a creative and personally defined end” (p. 134). Perhaps most importantly, children are able to practice bricolage, or tinkering, and to become bricoleurs, or tinkerers (p. 173, 175, 223), when learning in a microworld. The advantages of microworlds are many, and their disadvantages few. Jonassen (2000) considers microworlds to be environments that “encourage active participation” (p. 168), “provide instruction that is situated in rich, meaningful settings” (p. 169), and “support self-regulated learning” (p. 169). However, “their openness can be frustrating at first” (p. 169), and overcoming this may require students to acquire skills they do not posses. Microworlds can be an example of what Prensky (2006) calls a complex game (p. 58). In his discussion of Digital Natives and Digital Immigrants, Prensky (2006) describes Digital Immigrant’s games as trivial pursuits (or mini-games), except for a few exceptions, such as “chess, go, strategy games, and Dungeons and Dragons” (p. 55). Complex games: “Can take from 8 to over 100 hours to complete. Require players to learn a wide variety of often new and difficult skills and strategies, and to master these skills and strategies by advancing through dozens of ever-harder levels. May require both outside research and collaboration with others while playing. Often require players to assume alternate identities. Frequently present players with ethical dilemmas or life-and-death decisions. Often take from 20-60 hours to master. Include just about very electronic game that comes in a box, either for a PC or a console (PlayStation, Game Cube, or XBox), a well as many that are made for handheld devices such as GameBoys. Most simulation games (Sim City, Airport Tycoon, etc.), history strategy games (Civilization III and Rise of Nations), military strategy games, and sports games are complex games.” (Prensky, 2006, p. 58) However, just as not all video games are microworlds, Prensky (2006) cautions that not all video games are complex; “One-on-one arcade-type fighting games such as Virtua Fighter and other similar ones are just glorified mini-games" (Prensky, 2006, p. 59). It is the adaptability, worthwhile goals, and meaningful decision making that keeps kids playing complex games despite their relative difficulty (p. 60-63), and Prensky believes that “complex games, already educating our kids after school, also have the potential to be a huge boon to formal education” (p. 63). If one of the benefits of games is that they can provide an authentic context for student tasks, they can also provide support within this context, such that “learning even at its start takes place in a (simplified) subset of the real domain” (Gee, 2003, p. 137). This Gee (2003) called the Subset Principle (p. 137), and later “fish tanks” (2004, p. 61 and 2005a, p. 27), “supervised fish tanks” (2004, p. 65), “supervised sandboxes” (p. 66), “unsupervised sandboxes” (p. 70), and simply “sandboxes” (2005a, p. 27), but this might have been called a microworld by Papert and others. In a well-designed microworld, learners will see, “especially early on, many more instances of fundamental signs and actions than would be the case in a less controlled [context]” (Gee, 2003, p. 137). In the tradition of Papert’s microworlds, Aldrich (2004), too, is interested in the way “simulations describe small worlds” (p. 152) as a context for learning. The simulation he designed, Virtual Leader, provides a microworld in which players learn about leadership, a skill that is typically difficult to teach (and assess) in a traditional classroom environment. Shaffer offered several other examples of video games providing a microworld (or part of a microworld) in which students can learn and pursue meaningful goals. He was explicitly interested in “computational microworlds, which Hoyles, Noss, and Adamson (2002) define as 'environments where people can explore and learn from what they receive back from the computer in return for their exploration' (p. 30)” (Shaffer, 2005, p. 18). Shaffer (2006) later noted that “Every computer program creates a world: what Seymour Papert and others have called a Microworld” (p. 67). One example was an epistemic game called Escher’s World, in which students take on the role of a designer in training and in which a computer program called Geometer’s Sketchpad creates a mathematical microworld in which students can complete their designs (p. 84). In another epistemic game called Science.net, students “write using a journalism microworld whose features push back on specific elemsnts of writing to formula and writing as a watchdog” (p. 152). Each of the other epistemic games Shaffer discussed, including The Debating Game, Digital Zoo, The Pandora Project, and Urban Science also provide students with a microworld in which to learn by doing and thus practice thinking, acting, and innovating like a professional. Like Prensky, Shaffer believed that the “video games… of children’s culture today demand strategic thinking, technical language, and sophisticated problemsolving skills” (p. 6). And, in the tradition of Dewey, he believed that video games can provide a “simulated ‘world of hard conditions’” (p. 127). Another example similar to Shaffer’s epistemic games, is Supercharged!, a game discussed by Holland, Jenkins, and Squire (2003). They explain that “games present players microworlds; games offer players (students) contexts for thinking through problems, making their own actions part of the solution, building on their intuitive sense of their role in the game-world” (p. 28). The game was based on the concept that: "students have difficulty grasping core concepts of elctromagnatism because they run counter to their own real world experiences, yet playing a game that requires mastery of those principles in order to win may give them an intuitive grasp of how they work that can be more fully developed in the classroom" (Holland, Jenkins, and Squire, 2003, p. 35). Even so, they “do not believe that Supercharged! will ever replace Physics teachers, textbooks, or other educational materials. Rather, Supercharged! can be used as an instructional tool or resource within a broader pedagogical framework" (Holland, Jenkins, and Squire, 2003, p. 36). There are many ways in which even commercial off the shelf video games can serve as valuable microworlds for learning. Shaffer, Squire, and Gee (2005) explained that “video games are important because they let people participate in new worlds” (p. 105). Also, as Jenkins, Klopfer, Squire, and Tan (2003) explained, games can be “motivating and authentic” without being “dangerous and expensive” (p. 7). Furthermore, video games allow learners to “manipulate otherwise unalterable variables… [and] view phenomena from new perspectives” (Squire, 2003, p. 6). Ideally, a game used as an educational microworld will be similar to MIT’s Revolution, in which “the game world is big enough so that each student can play an important part, [and yet] small enough that their actions matter in shaping what happens” (Squire & Jenkins, 2003, p. 16). While it seems that role playing games, and in particular multiplayer games, can fit this bill, it is debatable whether or not MMORPGs are appropriate in this respect. Still, MMORPGs may be some of the best commercial examples of microworlds. As Steinkuehler (2005b) pointed out, “MMOGaming is participation in a multimodal, and digital textual place” (p. 98). She also explained that “within video games… the reader becomes or inhabits a symbol, enabling him or her to interact with signs as if they are the very things they represent” (p. 99), a property of video games that supports learners in transferring new skills to other environments. Transfer The transfer of skills from a learning situation to a real-world scenario is one of the goals of any educational system. Shaffer (2006) wrote that “impacts that transfer form one context to another are, in some sense, the holy grail of education, and certainly the ultimate goal in the development of educational games” (p. 157). Slator (2006) expressed this mandate by writing that “students who learn through simulations should acquire content-related concepts and skills as a consequence of playing the game, and this learning should transfer to knowledge contexts outside the game” (p. 4). In a serious game, such as biohazard, “understanding is to be performed in certain contexts” (Holland, Jenkins, and Squire, 2003, p. 38), and “games such as Escher’s World can accomplish, in a very general but very important sense, the elusive educational goal of producing worthwhile effects that transfer from one context to another” (Shaffer, in press, p. 4). Specifically, in the case of Escher’s World, “students were able to use the practices of the design studio to transfer the epistemic framework of developing and defending expressive solutions to open-ended problems from graphic design to mathematics” (Shaffer, 2004a, p. 1411). Pillay (2005) also established that skills acquired in a computer game do transfer to other similar activities, though the games and activities he studied were comparatively unsophisticated. In any case, while this sort of transfer may be the goal of any educational game, it is important to note that a game alone is unlikely to reliably produce this effect. As Squire (2002) warned: “playing Civilization might be a tool that can assist students in understanding social studies, but playing the game is not necessarily participating in historical, political, or geographical analysis. Therefore, building on our earlier discussion of transfer, there is very good reason to believe that students may not use their understandings developed in the game - such as the political importance of a natural resource like oil - as tools for understanding phenomena outside the game, such the economics behind The Persian Gulf War or contemporary foreign policy, even in a game as rich as Civilization III” (Squire, 2002, p. 9). The role of the teacher in supporting the development of student understanding remains important when games are used in formal education. (The role of the teacher will be addressed in greater detail in a later section. Situated and Distributed Understanding Learning that happens within a microworld (or other authentic context) is what constructivists consider situated learning, and allows students to develop a situated understanding of the skills they are developing and problems they are solving. Bruner (1996) believed that all knowledge is “always ‘situated,’ dependent upon materials, task, and how the learner [understands] things” (p. 132). Duffy and Jonassen (1992) also explained that constructivists “emphasize ‘situating’ cognitive experiences in authentic activities” (p. 4). Phrased another way, they believed that “we must aid the individual in working with the concept in the complex environment, thus helping him or her to see the complex interrelationships and dependencies” (p. 8). It is significant, especially in terms of microworlds and educational technologies, that they point out “the context need not be the real world of work in order for it to be authentic… rather, the authenticity arises from engaging in the kinds of tasks using the kids of tools that are authentic to that domain” (p. 9). In the constructivist tradition, Gee (2003) argued that learning involves situating (or building) meanings in context, and that “video games are particularly good places where people can learn to situate meanings through embodied experiences” (p. 26). He highlighted examples in which “the player (learner) is immersed in a world of action and learns through experience, though this experience is guided or scaffolded by information the player is given and the very design of the game itself” (Gee, 2005, p. 59). Gee (2003) understood that “meaning and knowledge are built up through various modalities (images, text, symbols, interactions, abstract design, sound, etc.)” (p. 111), which video games can provide in spades. Many scholars believe that video games and simulations can provide environments in which such situated learning can occur. Shaffer, Squire, Halverson, and Gee (2005), for example, stated that “the virtual worlds of games are powerful because they make it possible to develop situated understanding” (p. 106) and that “video games take advantage of situated learning environments” (p. 108). When discussing the new ways in which a student engaged with her world after playing the epistemic game Madison 2200, the authors wrote that “this is situated learning at its most profound – a transfer of ideas from one context to another that is elusive, rare, and powerful” (p. 109). Later Shaffer (2006) wrote about a journalism class (J-828) that inspired the epistemic game Science.net; “As the situated view of learning suggests, novice journalists in J-828 learned by becoming members of a community, and they came to see themselves as members of the community by learning to do things that members of the community do” (p. 148). Dede (2005), too, found that learning situated in virtual environments and augmented realities was important because of the capacity for transfer of learning to real problems. Steinkuehler, who studied MMORPGs specifically, was also interested in “the situated meanings individuals construct, the definitive role of communities in that meaning, and the inherently ideological nature of both” (p. 17). Just as they may provide students an opportunity for situated learning, many microworlds (and other authentic contexts) offer opportunities for students to developed a distributed understanding of skills and problems. Unlike in traditional testing situations, students do not need to memorize all of the answers to their problems and information required in the learning context. They can call upon tools and other individuals within the context to aid them in their efforts. As Bruner (1996) expressed it, intelligence is “not simply 'in the head' but [is] 'distributed' in the person's world - including the toolkit of reckoning devices and heuristics and accessible friends that the person could call upon... intelligence, in a word, reflects a micro-culture of praxis" (p. 132). Gee (2003) considered this one of the principles of good learning that many good video games do well; in good games “thinking, problem solving, and knowledge are ‘stored’ in material objects and the environment” (p. 111). Identity As students develop situated and distributed understanding within a learning context, they are essentially exploring an identity within that context – a way of acting and thinking that is specific to the context and problems at hand. Constructivist educators purposefully and explicitly support the development of educationally beneficial identities by their students. Some modern constructivists strive to help students develop professional identities that may be useful in their adult future, particularly professional identities that emphasize sophisticated or innovative ways of thinking, doing, and problem solving. Shaffer, Squire, and Gee (2005) believed that “the virtual worlds of games are rich contexts for learning because they make it possible for players to experiment with new and powerful identities” (p. 106). Shaffer articulates this well, with respect to his epistemic games: “the ability of students to incorporate epistemic frames into their identities (or portfolio of potential identities) suggests a mechanism through which sufficiently rich experiences in technology-supported simulations of real-world practices (such as the games described above) may help students deal more effectively with situations in the real-world and in school subjects beyond the scope of the interactive environment itself.” (Shaffer, in press, p. 19) Gee (2003) was most interested in the way that good games can facilitate learning by requiring players to take on a new identity and form “bridges from [their] old identities to the new one” (p. 51). He felt that “all deep learning – that is active, critical learning – is inextricably caught up with identity” (p. 51), and he tapped into the tradition of Piaget’s little scientists when he offered the example of “a child in a science classroom engaged in real inquiry, and not passive learning, [who] must be willing to take on an identity as a certain type of scientific thinker, problem solver, and doer” (p. 51). This concept he extended to the many roles that students might play in good role-playing video games, which he reported made him “think new thoughts about what [he as a player] valued and what [he] did not” (p. 56). He suggested that game designers and teachers “need to create a game-like biology world in which learners can act and decide as certain types of biologists” (Gee, 2005, p. 85) in order to help students become “authentic professionals [with] specific knowledge and distinctive values tied to specific skills gained though a good deal of effort and experience” (p. 51). Gee felt that good games can facilitate learning that “involves taking on and playing with identities in such a way that the learner has real choices” (p. 67). Citing Gee, Shaffer (in press) identified three levels of identity that can be developed in a game: “the real identity of the player… the virtual identity of the character or role the player has in the game… [and] a third projective identity, which is the kind of character the player wants to be in the game” (p. 19). He also discusses the importance of developing possible selves in a game; “possible selves give form to a person’s hopes for mastery, power, status, or belonging, and to a person’s fears of incompetence, failure, and rejection” (Shaffer, 2006, p. 158). With his epistemic games, Shaffer aims to “give adolescents new possible selves that are based on authentic experiences with innovative thinking that matter in the world” (p. 158). This experience can also extend to selves that are impossible in the real world. As Lahti illustrated, “this becomes a safe way [for players] to try on being a different race or sex” (p. 168). Steinkeuher (2006a) studied the nuanced development of such new identities in MMORPGs in particular (both in and out of game identities), suggesting that MMORPGs too might be a medium in which students might develop meaningful new identities. Role Playing One particularly powerful strategy for supporting this sort of identity development is to facilitate true role-playing experiences for students, in which each student takes on a specific role within a cognitively immersive environment. Story telling, especially in conjunction with student role-playing, can also be a powerful tool. Jonassen, Peck, and Wilson (1999) discussed “Role-Playing on the Web” (p. 33) and the creation of web-based simulations and games; they were especially interested in the promise of new technologies to allow even “elementary students [to] build simple to complex microworlds” (p. 33). Role-playing appeared again in their discussion of visualizing with technology when they suggested that students might “role play press conference(s)” (p. 66). This theme recurred yet again in their treatment of learning by constructing realities with hypermedia, where they shared a handful of examples of “anchoring instruction in hypermedia learning environments” (p. 92), which provide a scenario for the student to explore and play. Jonassen, Peck, and Wilson (1999) also mentioned the promise of text based MUDs (Multi-User Dungeons, and later Multi-User Domains) and MOOs (Object Oriented MUDs) as a powerful role-playing context for students (p. 140), where students can “can assume a virtual persona different from their real-world persona” (p. 141). These environments were also associated with “facilitat[ing] dialogue and knowledge building among the community of learners” (p. 200). Although “children enjoyed opportunities to choose their own paths through the environment, with some eventually learning to construct their own rooms and environments” (p. 141), there were some potential drawbacks to the use of these games in education; “boys seemed to show more interest than girls… [and] older children (11-14) participated more than younger children” (p. 141). Modern Multiplayer Online Role Playing Games (MMORPGs) are direct descendents of these early text based games, and may share some of the same potentials and drawbacks. Jonassen (2003) also this compelling vision of MUDs in the classroom, a vision that applies as much or even more so to modern MMORPGs: “Imagine, for instance, a MUD in which a student is placed on the main street in a small community in colonial America, with the option of entering stores, blacksmith shops, pubs, jails, homes, and other buildings of the period. Inside each building would be descriptions of the people and artifacts it contained. Students would make decisions and express their choices, to which the MUD’s characters and objects (and other students) would react. Imagine, too, that teachers and their classes could work together to develop new buildings. This option (which is often provided in MUDs) could be great incentive for research, collaboration, problem-solving, and other high-level activities.” (p. 104) These environments (MUDs or MMORPGs) also make natural microworlds, which Jonassen (2003) is still concerned with. Central to his philosophy is his belief that “transfer of learning, particularly higher order kinds of learning, requires well-developed mental models” (p. 190) and that “in order to construct mental models, learners must explore and manipulate phenomenon, observe the effects, and generate mental representations of those phenomena” (p. 190). This can occur in MMORPGs if they adhere to the four essential characteristics of a microworld, as Jonassen interprets Papert: “simple to understand reflects generic characteristics that can be applied to many areas of life presents concepts and ideas that are useful and important to learners in the world reflects syntonic characteristics, which allow learners to relate prior knowledge and experience to current phenomenon being studied” (p. 191) Jonassen later added the following: “Provides a meaningful learning context that supports intrinsically motivated and self-regulated learning Establishes a pattern whereby the learner goes from the “known to the unknown” Provides a balance between deductive and inductive learning Emphasizes the usefulness of errors Anticipates and nurtures incidental learning” (p. 193) In addition to the above, MMORPGs, like other games in general, “can embed cognitive, social, and cultural factors within the environment… which can help learners transfer skills from play and imitation to real situations that they will experience” (Jonassen, 2003, p. 191). Those that allow user creation within the game environment can tap into the idea that “the creation process is an important component of learning (Papert, 1980), which is supported with students constructing their understanding of a phenomenon in a microworld” (Jonassen, 2003, p. 197). Jonassen also points out that “as is the case with most instructional design projects, the people who learn the most are the designers and developers, not the target audience” (p. 191). With respect to virtual reality environments, which modern MMORPGs provide, Jonassen also suggests that active decision-making in the environment “gives students the feeling of participating in a realworld environment, and also transforms learning into exploration” (p. 205). More recent game scholars add a great deal to Jonassen’s work. Squire and Jenkins (2003) suggest that “games encourage role playing, which can… help students… to adopt different social roles or historical subjectives” (p. 28). For example, Jenkins, Klopfet, Squire, and Tan (2003) discuss the prototype Revolution, which “builds on… the value of combining research and role-playing in teaching historyu, that is, the game offers kids the chance not simply to visit a ‘living history’ museum… but to personally experience the choices that confronted historical figures” (p. 9). Shaffer (in press) concluded that by playing his epistemic games “students developed useful real-world skills and understandings in computer-supported role-playing games” (p. 3). The use of story in role-playing games can be a powerful tool for providing an emotionally meaningful context for student actions. As Grodal (2003) wrote, “video games are… the medium that is closes to the basic embodied experience” (p. 139). He went on to explain that in games the story is “developed by the player’s active particiation, and the player needs to posses a series of specific skills to ‘develop’ the story, from concrete motor skills… to a series of planning skills” (p. 139). Squire (2003) subscribes to the view that “interactive digital storytelling should emerge as a legitimate art form in the upcoming years, and video games seem to be paving the way” (p. 9). Holland, Jenkins, and Squire (2003) believe that “the heart of the game is its dramatic force; rather than a lecture, the player is compelled by a visceral or an emotional logic” (p. 39). Echoing core constructivist philosophy, they also note that “rather than regurgitating context-free facts, the player [of a role playing game] must take the next step and utilize knowledge in tense contextually rich situations” (p. 39) Naturally, such learning does not require a computer. Shaffer (2006) shared the example of The Debating Game, a face-to-face roll playing unit in which “students step into the roles of debaters and judges and play by the rules that define those roles” (p. 25). He notes that like Dungeons and Dragons, a pen and paper (tablet-top) role-playing game, “The Debating Game is a fantasy role-playing game… in which players take on the roles of debaters and judges to inhabit an imagined world in which they are making judgements about the morality of historical actors and about the skill of their own peers” (p. 25). The importance of role playing with respect to learning in video games will be addressed in greater detail in a later section. Providing a context for learning is an important element of a constructivist learning environment, but that context is much more powerful if it provides students with opportunities for inquiry.