Lecture: State and National Progressivism

advertisement

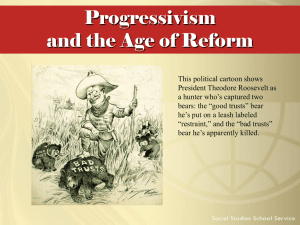

State and National Progressivism With networks of Progressive journals and journalists in place, Progressivism expanded beyond city-level reform. Two of the most flamboyant individuals in American history are responsible for expanding the Progressive Movement to the state and national levels almost simultaneously. Robert “Battling Bob” La Follette became the Progressive Governor of Wisconsin, and Theodore Roosevelt brought Progressivism to the whole country upon his ascending to the presidency in the wake of the assassination of William McKinley. A look at the lives of both men is a look at the American Dream as the 20th century opened. Bob La Follette led a life in Wisconsin similar to that of a sheriff in an old Western movie, a hero that cleaned up the town. He rose from obscurity to be the youngest member of the House of Representatives, a Senator, the Governor, and a presidential candidate. While he often resorted to patronage he served three terms as the Governor of Wisconsin and brought Progressivism to his state by 1900, making Wisconsin the envy of other Progressive-minded states. He worked his way through college and law school and took his brand of fanatically patriotic Protestantism on the campaign circuit around the state. He pioneered the tactic of barnstorming, or speaking wherever and whenever people would gather to listen, and it won him the District Attorney’s job without even being endorsed by his party, the Republicans. By 1884 he made his youthful debut in the House of Representatives but returned to practicing law when he was defeated in 1890. The Republican Party of Wisconsin indulged in Gilded Age graft with railroad and lumber companies. Party leaders tried to bribe La Follette to influence his brotherin-law, a judge, to ease up on regulation that hindered these industries. Not only did La Follette refuse the bribe, he exposed the whole affair to the press, forever cutting himself off from the Republican Party. He campaigned on his own for ten years and won the governorship in 1900. As Governor, La Follette developed a strategy to push a variety of Progressive reforms that became so successful it was referred to as the “Wisconsin Idea” as it spread around the country. La Follette set up independent regulatory commissions made up of experts. University professors in, say, forestry were called on to come up with ideas that “Back-to-the-People-Bob” could popularize. Can you think of anything more boring than listening to botany facts and statistics? But “Battling Bob” could take the plans from state university professors and barnstorm around in exciting attacks on the lumber giants. His persuasive leadership coupled with their scientific expertise created a startling new phenomenon in American politics, a government machine run by the educated elite but with the full support of an enthusiastic populace. This unstoppable combination has been used in one form or another ever since. A short list of immediate Progressive reforms reveals that whereas in 1900 half the states had no laws for a minimum age for workers, by 1914 all but one state set a limit. By 1917, 39 states shortened the work day for women, and 8 states had minimum wage laws for women. By 1916 2/3 of the states had workman’s compensation laws to protect and provide for workers injured on the job. Obviously, these are not the accomplishments of politicians looking out for the interests of big business. Progressives saw themselves as returning to the example of the Founding Fathers. Many Progressives, like La Follette, were independently wealthy and devoted their public service careers not to pocketing more money but to helping “the needy.” Progressive heroes imagined themselves possessed of “disinterested benevolence.” Unlike La Follette, Theodore Roosevelt was not a “self-made” man. His American Dream stemmed from his ancestors who were among the first to settle in New Amsterdam and who eventually established a glass-importing business. The Roosevelts, a name which means “field of roses,” were among the richest American “blueblood” families. Theodore’s father was a New York City banker, and TR was raised with all the privileged trappings of a Gilded Age upper-class lifestyle. Hampered by asthma, “Teedie” was told by his father at the age of six that he was brilliant, but besides being given a brain he was also given a body. “You are going to have to build your body,” his father told him as a gym was installed in the family home. TR was the first president of the United States to lift weights. From that point on TR was possessed of phenomenal, nearly obscene amounts of energy. His Harvard education made him an historian and a classical scholar, but his curiosity and drive made him an amateur naturalist, cow-puncher, Rough Rider, and big game hunter. In short, he was an American Renaissance man who entered politics because he said he wanted “to be among the doers.” He was also among the readers; he read a book a day his entire adult life. This bundle of energy was President at the age of 42, the youngest man ever to hold that office. After McKinley was shot in September of 1901 in Buffalo, New York, TR claimed to the Cabinet that he would continue all of the fallen President’s policies. There was an audible sigh of relief in the room. Within one year, however, TR was challenging Congress at every turn. By 1909, after winning a second term in his own right, TR had launched Progressive Reform at the national level and made the US President the most powerful individual in America and in the world. While not every president has since deserved or wanted that status, they possessed it because of TR. He called the presidency a “bully pulpit,” from which he preached that the benefits of being a member of the wealthy class and a Harvard graduate entailed social responsibility. He laid the foundations, therefore, for the modern welfare state. TR’s social conservatism and pugnacity were mixed perfectly with political shrewdness to make him a powerful reformer. He is by far the most eager man to have ever been president. His rise to power is a stunning arc of talent that began with being elected to the New York legislature as a Representative. He ran for mayor of New York City next (and lost), but his career received a sudden blow with the death of his first wife and his mother in the same house on the same day in 1884—Valentine’s Day! To escape these tragic events he bought a ranch out in the Dakota Territory and worked right alongside his cowhands. He became famous for knocking a cowboy out cold who had called him “four-eyes” in a bar and for admonishing one of his workers on a cattle drive by shouting, “Hasten forward thither!” He also became famous for writing The Winning of the West, a multi-volume history of westward settlement that was nationalistic, patriotic, and filled with biographies of heroic expansionists. Throughout the work he expressed Federalist opinions going so far as to call Thomas Jefferson a “humbug and a hypocrite.” These exploits brought him to the attention of President Benjamin Harrison who placed the energetic young man on the United States Civil Service Commission from 1889-1895 where TR received much publicity by being a Republican who actually believed, much to Harrison’s surprise, in civil service reform. Even greater publicity came with a new post as the New York City Chief of Police. TR and his friend, Jacob Riis, would sneak around at night to catch corrupt cops and violators of liquor laws. Riis took photos of TR catching the offenders red-handed, and the photos appeared in newspapers, making TR’s teeth, moustache, and glasses famous. Roosevelt would work all the next day after a night out to avoid letting his desk work get behind, then stay up the next night to go out and catch some more evil-doers who assumed he would be home in bed. Then he would go to work the next day so that no one could say he was a slacker at the office. How many hours was he awake by then—60? These exploits brought him to the attention of William McKinley who made him, as we have seen, the Assistant Secretary of the Navy where he read Mahan’s book and operated with nationalistic and militaristic views. When war broke out with Spain, TR sought to enlarge his heroic image by resigning from the Navy Department and mustering the Rough Riders. We last left him exulting after the charge up San Juan Hill that he got to shoot a Spaniard in the stomach saying afterward that the enemy soldier “crumpled like a rabbit.” This heroic image was tempered by the fact that TR had stashed a dozen pair of glasses all over his uniform apparently terrified that an accident would leave him blind. All the nation saw, however, was his gallant flesh wound and his triumphal return to win as Governor of New York. His Rough Riders even rode around and shot their weapons in the air during his campaign. His meteoric rise did not stop. Despite the fact that he had begun to show Progressive leanings, William McKinley took him on as his Vice President. The Republican Party wanted to capitalize on TR’s fame but imagined the nearly useless role of VP would “keep him harmless.” Mark Hanna, however, reminded the Republicans that only one heartbeat stood between “that Madman and the Presidency.” And that noble heart stopped. I say noble because I can never forget McKinley’s treatment of his wife who had a bizarre condition that prompted her to occasionally have spasms of the face that caused her to make “demonic” expressions, even during state dinners. When such an episode took her, President McKinley would merely take out his handkerchief and cover her face until the fit was over. Then he would resume conversation as if nothing had happened. How could an assassin shoot a man who was that kind? The Madman was President, though. TR was an opinionated storyteller that had to be the center of attention wherever he went, and he always arrived 15 minutes late to let anticipation build. His relatives, Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt, said that TR had to be the “bride at every wedding and the corpse at every funeral.” He commented on everything. He hated Emile Zola’s novels (banned by obscenity laws); he liked “full baby carriages, football players, and reform.” He was incessantly active and hunted or hiked whenever possible, usually with visiting dignitaries in tow, panting. His second wife’s parlor was the one room at Sagamore Hill, the family home on Long Island, not covered with game heads, and it even had a polar-bear rug. He is the only president to be an amateur boxer and lost the sight in one eye in the boxing ring, a fact he demanded be kept secret. He claimed he would never be assassinated because his reflexes were too quick. While he is not the man to originate the saying, TR is the first president of the United States to believe, “America should order the affairs of the rest of the world.” While we are dealing with domestic Progressive reforms, be assured we will return to TR’s incredible importance in foreign policy later. For now suffice it to say he was a cartoonist’s dream to caricature, and his trademark smile became famous the world over. His motto was, “Get action! Do things!” When asked what should be done with a mob he responded, “Take 10 or 12 of their leaders out and shoot them!” When asked what should be done with Socialists in America he said, “Surround them with soldiers intent on doing them harm!” When asked if he liked Folgers coffee he said, “It’s good to the last drop,” and that has been their company slogan ever since. Don’t think of TR as a buffoon, though. He loved it when people underestimated him. He was our first historian president. His keen awareness of the foundations of the country and his understanding of the lessons of the Civil War (he was the first president to have a Union father and a Confederate mother) pointed to Federalism. He admired the United States as a republic of self-denying gentlemen but said we had filled the continent and industrialized rapidly without deserving to do so. He said America had not devised a system of management to which we could safely entrust the legacy of the American Revolution in the modern world. He announced he was the manager to do it. Just like his genius coffee slogan, he coined the name of his domestic program spontaneously while in the West on a 262-speech tour. TR loved public speaking and always leaned forward on the tip of his toes with his over-large head appearing as if he were about to plunge into the crowd. He snapped his teeth together audibly as he spoke. Once, in reference to Indians, he said they deserved a “square deal” from America. At another speech he said the magic words in reference to blacks. Each time the crowd interrupted him with uproarious applause, so he kept it. He even came up with an easy way for journalists and citizens to remember his program. The Square Deal had three “Cs.” The first on the agenda was the Control of corporations. TR believed in direct national economic development. When the nation was casting about for who would make the determination in enforcing the Sherman Anti-Trust Act’s language of “unreasonable restraint of trade,” TR suggested that he could do it. He believed there were “good” trusts and “bad” trusts and gained his reputation as the Great Trustbuster by taking down only those trusts that “misbehaved.” He established a Bureau of Corporations within his new Department of Labor and Commerce and gave this new regulatory commission a characteristically brusque name, “Watchdog Agency.” Even after being the second president to ask J. P. Morgan to personally boost the American economy, he attacked Morgan’s railroad, the Northern Securities Company, and US Steel. To prove that the President was sovereign economically he intervened in the strike of the United Mine Workers and forced them and the coal mine owners to accept his terms. TR argued that since the US Navy ran on coal, a slowdown in the production of coal was a national security issue. He threatened, therefore, to take over the mines and work them with the US Army. The mine owners were forced to pay 10% higher wages and to shorten the work day. Consumer protection was the second component of the Square Deal. TR pushed the Pure Food and Drug Act and the Meat Packing Act through Congress in 1906 after reading The Jungle by Upton Sinclair, an expose of the muck raked up in meat packing plants and included in the sausage. While Sinclair was trying to make the nation accept Socialism, he managed only to make the President physically sick. Sinclair said he aimed at the heart of America but hit them in the stomach. Regulations poured out of Washington to protect consumers but wound up driving small competitors out of business and raising the price of meat dramatically. Regardless of federal inspections, by the way, I still suggest you cook all meat before eating it. Theodore Roosevelt was a hunter but also a nature lover, and Thoreau and TR’s friend, John Muir, did not entirely convince the President of the advantages of leaving the wilderness pristine. The third component of the Square Deal was therefore Conservation of natural resources which TR defined as “developing” those resources in the hands of scientific experts. Thus the field of natural resource management was born. TR set aside 43 million acres as national forests, 53 wildlife refuges, and 65 million acres of coal reserves. TR’s administration permitted big corporations to purchase permits to acquire access to the coal to avoid exploitation. TR was in control. But he did not choose to exercise his Constitutional option to run for the presidency again, at least not yet. He honored Washington’s two-term precedent and hand-picked William Howard Taft to succeed him, only the second time a president could do such a thing. TR expected Taft to carry on with a nation far more accustomed to a strong president with national unity and big government solutions to national problems. TR’s integrity, guts, and energetic service made the presidency dominate the 20th century with a legacy of a government bureaucracy of “experts.” While Taft set aside more land and busted more trusts, TR was remembered as the Trustbuster and the Great Conservationist. The two men were not to remain allies for long.