Fiscal Responsibility and Cost Allocation Tools

advertisement

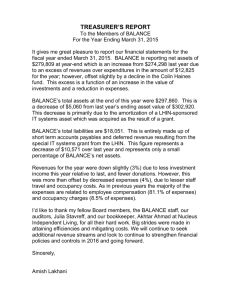

Fiscal Responsibility and Cost Allocation Tools for Small and Medium Size Entities PRESENTED BY DANIEL W. BRADLEY, CPA OF YOUNG, OAKES, BROWN & CO., P.C. ALTOONA, PENNSYLVANIA IN CONJUNCTION WITH THE COMMONWEALTH OF PENNSYLVANIA’S OFFICE OF CHILD DEVELOPMENT AND EARLY LEARNING WITH THE ASSISTANCE OF THE BRAIDING PRESCHOOL FUNDING TASK FORCE INDEX CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION TO BRAIDING FUNDING CHAPTER 2 TOOLS AN ORGANIZATION NEEDS TO BE SUCCESSFUL CHAPTER 3 PRESCHOOL PROGRAMS AND FUNDING CHAPTER 4 COST ALLOCATION PRINCIPLES CHAPTER 5 WORKSHEETS AND GUIDELINES CHAPTER 6 CASE STUDY INVOLVED WITH USING THE WORKSHEETS FOR A SAMPLE ORGANIZATION APPENDIX A DEFINITION OF TERMS USED IN THIS WORKBOOK RESOUNCES APPLICABLE WEBSITES The Commonwealth of Pennsylvania’s Office of Child Development and Early Learning would like to express its sincere gratitude to the members of the Braiding Preschool Funding Task Force CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION TO BRAIDING FUNDING BACKGROUND OF ‘BRAIDING FUNDING’ Under the Rendell Administration, multiple new preschool funding streams were established to promote the early education agenda and prepare the Commonwealth’s young children for school success. As a result of the new funding streams, the Office of Child Development and Early Learning (OCDEL) convened the Braiding Funds Task Force with the goal of assisting early education and care providers to utilize the funds appropriately and efficiently. The Task Force looked to assist providers in understanding the fiscal requirements of the different programs, how these requirements worked in relationship with each other, and how to braid the funding to achieve the next level of best practice in fiscal accounting. OCDEL in partnership with key early education and care practitioners from programs representing all OCDEL funding streams came together to consider the issues and prepare materials to assist providers in improving their practices. TARGET AUDIENCE The target audience for this manual and professional development opportunity is administrators and fiscal staff of small and medium size programs already using basic budgeting techniques, who wish to develop a deeper understanding of the concepts around cost allocation and management of multiple funding streams. Ideally the program administrator and the fiscal staff member would attend the workshop together in order to best support the continued development of the fiscal practice at the site. To receive the best results, program management and fiscal operations must be inextricably linked together in overall program management. OBJECTIVES Review of the material in this chapter will enable participants to: Understand and apply a number of basic accounting principles from the ‘tool kit’ to program operations Define “braiding” of preschool funding Derive the benefits associated with braiding funds 1-1 DEFINITION OF BRAIDING PRESCHOOL FUNDING The use of multiple sources of public and private funding to support program operations and services to individual children, with each source or thread of funding traceable and identifiable from a management and accountability perspective. Together the threads braid together to form a rope of coherent support for programming for children. To properly braid funds, appropriate cost allocation methodologies must be used and applied, assuring that there is no duplicate funding of the costs of services or programs. WORKING WITH ACCOUNTANTS Programs are encouraged to use these materials in conjunction with the advice of an accountant/auditor and well trained fiscal staff. The needs of a particular organization depend on various requirements. For example, in some cases, due to a law, regulation, contract, or agreement, an organization may be required to undergo an annual financial statement audit. If this is the case, the organization’s auditor can be an invaluable asset for providing advice, technical assistance, and training on many topics including braiding funding. In the United States, audits can only be conducted by Certified Public Accountants (CPAs); however, much accounting and auditing work is performed by uncertified individuals, who work under the direction and supervision of a certified accountant. A CPA is licensed by the state of his/her residence to provide auditing services to the public, although most CPA firms also offer accounting, tax, litigation support, and other financial advisory services. The requirements for receiving the CPA license vary from state to state, although the passage of the Uniform Certified Public Accountant examination is required by all states. This examination is designed and graded by the American Institute of Certified Public Accountants. With that being said, many organizations have no legal requirement to undergo an annual audit, and, as a result, many accountants, who may not necessarily be CPAs, can provide much of the same assistance mentioned in the preceding paragraph and more. An auditor is somewhat limited in the services he/she may provide to an auditee, that is, the organization being audited; however, an accountant who is not auditing the entity is free of many of those restrictions and, as a result, can actually act as a member of management. From an organization standpoint, the key is finding a qualified individual to act as your auditor or accountant. Ask for and follow-up on references from organizations like yours. The selected individual must be someone that the organization is comfortable with, but also must be well qualified to serve your organization. Accounting principles vary by industry and as a result, the selected organization must be familiar with the appropriate accounting principles governing your organization. 1-2 CHAPTER 2 TOOLS AN ORGANIZATION NEEDS TO BE SUCCESSFUL Introduction Many early learning programs resist operating like a business because management feels that focusing on mission fulfillment will be enough to continue in existence. The future presents challenges to many organizations as the demand for public funds and private contributions becomes more competitive. As a result, organizations must operate both efficiently and effectively by avoiding attributes that lead to poor performance and the inability to deliver service in a cost-effective manner. Organizations that operate both efficiently and effectively employ business tools and techniques that result in profitability, such as: Strategic plans Budgets Accurate and appropriate interim financial statements Proper cost assignment and allocation Dashboard to highlight significant variances Proper resource management Effective internal controls Cash management Unfortunately, many organizations fail to use the above mentioned tools. Efficient and effective management of early learning programs requires an acceptance by management that a focus on financial management and the use of business tools does not taint the mission, but rather enhances the operations of the entity. The organization’s board as well as its program and fiscal management must embrace appropriate business techniques; and both program and fiscal management must show a willingness and desire to learn about and utilize business management tools appropriate to their organization. 2-1 Every organization must operate within its means or have the ability to generate more resources. Planning and budgeting, appropriate cost allocation and cost assignment, appropriate internal controls, adaptability, the utilization of on-going performance measures, appropriate marketing strategies, and proper human resource management greatly enhance the organization’s chance of success well into the future. The Toolkit Various tools, techniques, and strategies are utilized by successful organizations. This section will introduce and explain several of these tools, techniques, and strategies. Business Plans Business plans are the long-term (five to ten years) guides that organizations follow to fulfill its mission. The business plan provides the link between the mission and the actions to attain the desired outcome based upon opportunities available to the organization due to the skills and expertise of the organization’s staff, as well as their commitment to the organization’s mission. The business plan explains what an organization does and why it exists. Budgets A key component of the business plan is an organizational budget that provides direction, control, and a start to future year’s budgets. Budgets should always be prepared at the program level, and then pieced together to arrive at an organizational budget. Expenditures should be classified by natural category (i.e. salaries, benefits, rent, etc.) as well as by functional categories (program versus management and general versus fundraising) by program to assist in outcome measurements. Program expenses are related to the mission statement. Management and general expenses are incurred to operate the organization and not directly related to the performance of the service. Fundraising expenses are those incurred principally to solicit resources. As mentioned previously, a business plan should be for the long-term (5 to 10 years), and, as a result, a budget for each period should also be prepared. With that being said, do not become married to the budgets contained in the business plan. Things do change and, therefore, consider each year individually. As the organization begin preparing its next year’s budget, staff should not assume that just because the organization had a certain expense in a prior year that that expense is valid for the current year. The organization needs to assign revenues and expenses to its projected operations. This process must be done in a realistic manner and not with an overly optimistic or pessimistic slant. If during this process, something does not make sense, investigate why immediately. Don’t wait until you actually have a problem. 2-2 Typically, the organization should determine the amount of projected revenue before determining expenses, since an organization cannot spend what it does not have. Certain expenses are relatively fixed or only impacted by inflation. An organization should first project these expenses. Next, project the remaining expenses based on what it will cost to achieve the organization’s goal for next year. Determine these remaining expenses in terms of dollars based upon how much labor will be needed, what benefits will be provided, what payroll taxes are required, how much is needed in the area of supplies, etc. Now that the organization has estimated current revenues and expenses, how did we end up, that is, do we have an excess of revenues or an excess of expenses? If we have an excess of expenses, do we have unrestricted net assets that we brought forward from the prior year in sufficient amounts to cover the excess? If not, the budget may needs to be revised; however, we also need to consider other sources of cash. For example, does the organization have an available line of credit to cover the shortfall in the current year, or are there certain fixed assets that are not currently needed that could possibly be sold. The planning process never ends. The current year budget should be compared to actual events on a continuous basis; however, the current year budget should not be changed unless a new funding source becomes available, a new program is started, or some other unanticipated significant event occurs. Key Financial Statement Consideration and Performance Measurements Financial Statements communicate the measure of performance, success and accountability of an organization. Financial ratios/analysis include budget comparisons, trends, and financial statement relationships expressed in analytical terms. Cash is the most liquid and desired asset. One of the skills required by every successful organization is the ability to manage its cash in order to permit it to pay its current bills. Management frequently is confused when the increase in net assets for the year does not translate into an increase in cash. The cash flow statement details how much cash was provided or used from operating activities, as well as from investing and financing activities. A cash flow statement reconciles the net income or loss of the organization to the changes in its cash balance during the period. After considering cash, an organization also needs to be aware of its working capital, (the excess of current assets over current liabilities). To properly and easily determine its working capital an organization should use a classified balance sheet, separating out current assets and liabilities, fixed and other assets, and long-term liabilities. 2-3 The executive director and the Board are frequently provided with a list of the organization’s current cash position as well as what bills are due within thirty days. In some cases, due to revenues not coming in as timely as they should, an organization should have available short-term financing to cover temporary cash shortfalls. To stretch every available dollar as far as possible, a successful organization takes advantage of cash as well as volume discounts. A cash discount is available if bills are paid within a specified period, while volume discounts result when organizations buy in larger quantities. A few simple “dashboard” type calculations/ratios can alert management to potential problems on a timely basis. Many early childhood programs use an enrollment report that compares staffed capacity to enrolled capacity. Most programs develop the revenue estimates based on the numbers of children that can be served. Since most early childhood programs have staff salaries and benefits as a high percentage of the budget, insuring that enrollment is sufficient to support the staffing patterns is critical. Immediate measures must be taken when these areas are out of sync. Other extremely useful management tools are comparative analysis. Comparing your budget to actuals on an on-going basis highlights significant difference between actual results and expectations, with a review to determine the cause of the variance and whether the expenses are truly needed. Trend analysis compares financial statements amounts for multiple periods in a side-by-side format. Common-size statements restate all financial statement components as a percentage of a common denominator. As mentioned earlier, working capital is the excess of current assests over current liabilities – a margin of safety, if the organization timely retires all of the current obligations using the current assets. The current ratio, i.e. current assets/current liabilities, is another measure of liquidity, where if the current ratio is less than 1:1, the organization lacks sufficient current assets to pay all current liabilities. The receivables to working capital ratio (Accounts receivables/working capital) may be indicative of collection problems. The number of days in working capital ratio (budgeted expenses for the year/365/working capital) determines the number of days an organization could stay in existence with no other revenues being earned. Whenever the number of days in working capital drops below an established level, the organization needs to review its collection efforts, reduce budgeted expenses, or seek credit on a long-term basis. Cost Allocation/Assignment Cost Allocation/Indirect Cost Plans assist decision makers on an on-going basis, provide cost control, and measure compliance with requirements. 2-4 Cost assignment is usually associated with a direct cost, while cost allocation is associated with indirect costs. Assigning direct costs is typically not an issue, because the classification is usually obvious. Indirect expenses are usually less obvious because they serve more than one purpose. Costs allocation can be accomplished in a variety of ways. First, determine to what cost center/function/program indirect costs should be allocated. Next, determine an appropriate cost driver, such as direct labor hours/dollars or square footage, that will be used as the basis to allocate/drive out the costs. Costs are allocated and assigned for several reasons. Generally accepted accounting principles require financial statements to be cost allocated by functional categories for nonprofit organizations. A grantor may specify that only certain costs are permitted to be charged against their grant, which may necessitate cost allocated to a grant and also by functional categories, if there is a limit on certain types of costs, such as administration. To determine the true cost of an activity in order to determine the amount to charge for a service, cost assignment and allocation is imperative. Internal Control Procedures Internal control in any organization is the responsibility of management. As part of continuous quality improvement, organizations should evaluate the need to change, update or modify procedures. Internal control is a process, which is affected by those individuals on the Board, within management, and the organization’s staff, designed to provide reasonable assurance about the achievement of the entity’s objectives with regards to reliability of financial reporting, effectiveness and efficiency of operations, and compliance with applicable laws and regulations. Internal control consists of five interrelated components: Control environment o This component encompasses the individual attributes of its people, including their integrity, ethical values, and competence as well as the environment in which they operate. It includes tone at the top of an organization. Control environment establishes the foundation for the remaining components. Risk assessment o Every entity must be aware of the risks that it faces. It must set activities and objectives so that the various components of an organization are working in conjunction with one another. An entity must establish mechanisms to identify, analyze, and manage the related risks. 2-5 Information and communication systems o These systems enable the entity’s employees to capture and exchange the information needed to conduct, manage and control its operations. Control activities o An organization’s policies and procedures Monitoring o The entire process of an entity must be monitored on an on-going basis and modification made if necessary. Policies assist management in the communication of established and approved procedures. They also communicate the mission, goals, objectives, and operating style of management. They can motivate and control. Risk of financial loss is inherent in any organization. An organization must attempt to reduce the risk of loss as part of its stewardship obligation. As a result, it is imperative that an organization’s governing body, management, and other personnel understand the controls that exist so that the risk of loss can be assessed, controls can be monitored, and necessary controls can be improved or implemented. Often controls are required by the funding source, program standards, or at the discretion of program management and need to be carefully considered and incorporated. Some common controls that reduce the risk of loss include using an appropriate accounting system; having written policies and procedures; using prenumbered purchase orders, invoices, receipts, receiving reports, and checks; reconciling bank accounts in a timely manner; signing checks after reviewing all appropriate, original documentation; maintaining an imprest petty cash system (where the receipts and remaining cash always equal some fixed dollar amount) reconciling underlying details to general ledger balances on an on-going basis; requiring dual signatures on checks; depositing all receipts intact on a daily basis; exercising appropriate oversight by the board of directors; and performing background checks on all new hires. With the above being said, before implementing any internal control, an organization must assess the cost/benefits of implementing that control. Only those controls where the benefits exceed the costs should be implemented. Some of the risks facing an organization are insurable risks. Examples of insurable risk include damage to property due to fire, flood, earthquake, or other natural disasters; injury or loss of life to individuals on your premises; theft or vandalism of property; property damage or injury to persons involved in an automobile accident, where the automobile is owned by the nonprofit or operated by the organization’s employees or volunteer while performing duties for the organization; and claims against directors and officers for personal liability resulting from actions by the organization or by the directors in the performance of their duties. 2-6 As it relates to directors’ and officers’ liability, directors and officers, while performing their official duties, must act in good faith and in the best interests of the organization. Many states have enacted The Model Business Corporation Act, which defines a director’s duty of care as that of an ordinary prudent person. A general rule is that directors or officers will not incur personal liability for the torts of an organization merely by reason of their official capacity. Such individuals are not liable for torts committed by or for the organization unless they participated in the wrongful act. Many states have also enacted legislation that indemnifies an officer or director of a nonprofit organization, if that officer or director receives no compensation for his or her services as an officer or director. Another risk facing an organization is the risk of loss due to fraud. Two types of fraud that affect organizations: management fraud or fraudulent financial statements employee fraud or theft of assets The best defense against fraud is an appropriate internal control system, which might include a whistleblower program and/or a hotline. Human Resources Management Salaries, payroll taxes, and fringe benefits usually comprise between 60-85% of the costs of operating many early education and care organizations. As a result, management must possess the requisite skills to deal with complex payroll issues as well as the required personnel management skills. Periodic performance reviews are an excellent time to discuss with the employees the value of the benefits provided to them, the value of the employee to the organization and the need for any improvement on the part of the individual. Other effective and valuable tools to use in relation to personnel management are: Formal, written job description for all employees to assist employees understand their duties and what is expected of them An organizational chart that graphically depicts where each employee fits within the organization and the authority and responsibility of each position Personnel manuals that explain what is expected of all employees. 2-7 As it relates to payroll issues, a nonprofit is treated like a for-profit entity to a large degree. The same payroll taxes and reporting responsibilities, except that 501 (c)(3) organizations are exempt from the Federal Unemployment Tax Act, apply, including Federal Insurance Contributions Act (Social Security or FICA); federal, state and local income tax withholdings; State Unemployment Tax Act (SUTA); Immigration Reform and Control Act, in which an employer must only hire individuals who can legally work in the United States; Child Labor Laws; Fair Labor Standards Act, which deals with minimum wage requirements for non-exempt employees; and the New Hire Reporting requirements, in which all employers must report certain information regarding newly hired employees to a designated State agency to locate parents, establish/enforce an order for child support payment as well as to detect and prevent erroneous benefit payments under unemployment and workers’ compensation programs. Substantial penalties from the Internal Revenue Service, state, and local taxing agencies exist for noncompliance, including noncompliance related to nonpayment of taxes, late payment, late filings, and filing incomplete or erroneous returns. To reiterate, management must have an intimate knowledge of their responsibilities related to the referenced reporting requirements as well as other legally mandated requirements related to payroll tax management and reporting to minimize the exposure to significant penalties that can result and that have forced some organizations to close their doors due to an inability to survive these penalties. Certain penalties can also be assessed against the individual(s) responsible for payment and reporting who failed to do so. This is an extremely important part of the job of management and should not be relegated to an insignificant role within the organization. Professional services exist that provides these services. If an organization had problems in this area previously, get professional help for these services—they may come at a cost, but they are extremely beneficial compared to the potential penalties for noncompliance. The Employee versus Independent Contractor Issue Many organizations utilize independent contractors versus employees, and, as a result, save payroll tax and employee insurance cost. These independent contractors also benefit by not having taxes withheld from their checks and can take advantage of various tax benefits. As a result, on occasion, an organization and the individual may agree to treat the individual as an independent contractor versus an employee, when in fact the opposite is proper. These situations have caused many abuses of the employment tax laws. An organization frequently needs to offer a variety of employee benefits to attract and retain qualified employees. Some of the more commonly offered fringe benefits are health insurance; life insurance; vision and dental insurance; disability income insurance; paid holiday, sick and personal days; workers’ compensation; family and maternity leave; retirement plans; employer provided child-care; and education assistance. All of these employee benefits come at a cost to the organization, and, as a result, the organization should make it clear to its employees the value of these benefits. Frequently, the costs of benefits as well as required payroll taxes add in excess of 40% to the wages paid to employees. 2-8 The Roles and Responsibilities of the Board of Directors Under the law a director has a duty of care as well as a duty of loyalty. These duties require a director to be well informed and active, while exercising prudent care when acting in his capacity as director, ensuring that the director always put the organization’s best interest above his own or that of any other organization or person. By doing so, the director should avoid actual or perceived conflicts of interest. The board has a responsibility to ensure that management is conducting its affairs in an appropriate manner. This does not means that the board must micro-manage the organization, but by the same token, the board cannot simply assume that management is acting in a proper way. The board must be vigilant in looking out for the best interest of the organization and find that delicate balance between micromanaging and being hands off. SPECIAL CONSIDERATRIONS FOR A NON-PROFIT ORGANIZATION The Privileges and Responsibilities of a Nonprofit By virtue of being a nonprofit organization, the Internal Revenue Service and State governments have granted non-profit organizations certain privileges; however, with privilege comes responsibilities. Usually the government’s involvement with organizations is geared toward protecting the nonprofit organization and fostering an environment conducive to the purposes and activities of most organizations. Some of the privileges granted by the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) include favored tax status through tax exemption. In addition, Section 501 (c) (3) organizations are granted the ability to solicit tax deductible contributions from donors. In return for these privileges, the IRS monitors the actions of organizations to ensure that the applications filed with and approved by the IRS continue to hold true as the nonprofits conduct their activities. Organizations that have been granted exemption may lose their privileges if they engage in certain prohibited transactions or activities. Organizations granted tax exemption under either section 501(c) (3) or (4) are subject to the Excess Benefit Transaction rules, known as the Intermediate Sanctions Law. An excess benefit transaction is any transaction in which the economic benefit is provided by either a section 501(c) (3) or (4) organization, directly or indirectly, to, or for, the use of any disqualified person if the value of the economic benefit provided exceeds the value of the consideration (including the performance of services) received for providing such benefit. A disqualified person generally includes a person who, at the time of a transaction deemed an excess benefit transaction, or at any time during the three years immediately preceding the date of the transaction, was in a position to exercise substantial influence over the affairs of the organization. 2-9 A disqualified person (which can include relatives of the disqualified person) who is determined to have received an excess benefit is liable for an excise tax. In addition, the disqualified person will be required to pay back the excess benefit to the organization, or be subject to an additional penalty for the excess benefit. Managers of organizations who engage in excess benefit transactions are subject to additional excise taxes. All organizations are subject to a variety of laws and regulations. Many organizations receive grants and subsidies from various branches of governments. As a result of accepting these grants and subsidies, the organizations typically have additional rules and regulations to comply with that are unique to the grant or subsidy. Most organizations are corporations in which states have granted legal substance by virtue of filing their articles of incorporation and by-laws with the state. Corporation can enter into contracts that are enforceable under the law, can sue and be sued, and can be subject to enforcement of the laws of the local, state, or federal government. Like any corporation, the nonprofit should maintain adequate board minutes, retain all contracts, retain their articles of incorporation and by-laws, retain its notification from the IRS of tax exemptions granted, and retain all audits and IRS or required state filings. IRS Reporting Requirements for Nonprofit Entities Organizations whose gross receipts are normally more than $25,000 per year must file an annual information return, Form 990. Organizations whose gross receipts are less than $100,000 during the year and whose total assets are less than $250,000 at the end of the year may usually file Form 990 EZ. An organization whose gross receipts are normally less than $25,000 per year are required to electronically file a postcard, Form 990-N, with the IRS. Most states exempt non-profits from taxation of income, but require the filing of an information return. Many states accept a copy of the federal Form 990 or Form 990EZ in lieu of requiring the detail to be included on the state prescribed form. Organizations that engage in business activities or own income producing property may be required to file, in addition to their Form 990, a Form 990-T and pay any tax that is due. Any nonprofit organization, normally exempt under Section 501(a) of the Internal Revenue Code, must file Form 990-T if it has annual gross income from an unrelated trade or business in the amount of $1,000 or more. The IRS defines gross income as the gross receipts, minus the cost of goods sold. Unrelated trade or business income is the gross income derived from any trade or business that is regularly carried on and is not substantially related to the organization’s exempt purpose. An organization, that is required to file Form 990 and that fails to do so, is subject to a penalty of $20 per day for each day the failure to file continues. The maximum penalty for each return required to be filed is the lesser of 5% of the nonprofit’s gross receipts or $10,000. The penalties and maximum limits are increased for nonprofit organizations with annual gross’ receipts in excess of $1 million. 2-10 Lobbying The IRS does not permit 501(c) (3) organizations to participate in the legislative process to more than an insubstantial degree. The IRS will consider an organization to be carrying on lobbying activities, if it contacts or urges the public to contact at any government level, members of a legislative body for proposing legislation and supporting legislation, opposing legislation, and advocating the adoption or the rejection of any legislation. Direct lobbying involves directly communicating with a member or an employee of a legislative body or with a government employee or official who can participate in the creation of legislation. Grass-roots lobbying involves an attempt to influence the opinions of the general public or a sector of the general public. Determining what constitutes an insubstantial amount of lobbying requires judgment; however, a nonprofit may make a safe harbor election with the IRS to abide by dollar ceiling amounts of expenses it incurs in lobbying activities. The dollar ceiling amounts are based on a sliding scale established by the IRS, in which the allowable percentages of total exempt expenditures decrease as total exempt expenditures increase. By making this election, the nonprofit takes the judgment out of the determination of what is meant by insubstantial. If it is determined that a nonprofit has exceeded the insubstantial limit of lobbying activities, it is subject to a substantial excise tax on the excess expenditures. Political activities differ from lobbying. Political activities involve participation or intervention, whether direct or indirect, in a political campaign on behalf of, or in opposition to, a candidate for public office at any government level. Direct or indirect participation or involvement includes making statements supporting or opposing a candidate, or publishing or distributing statements that support or oppose a candidate. If your nonprofit is determined to have carried on any political activity, it will lose its tax-exempt privilege. Private Inurement This is another situation in which an organization’s tax exemption will be lost. Private inurement results when the assets or revenues of a nonprofit benefit an individual or other non-tax-exempt entity. Examples of private inurement are excessive compensation to an individual; or where an individual other than a beneficiary of the entity’s mission may be allowed to use, rent free, an asset of the tax-exempt organization. 2-11 AUDITS GAAS versus GAGAS versus OMB Circular A-133 An organization that is required to have an audit conducted can be subject to three different levels of audits. The three levels of audits are those conducted under: Generally accepted auditing standards (GAAS) Generally accepted government auditing standards (GAGAS), also known as a “Yellow Book” audit The Office of Management and Budget of the United States (OMB) Circular A133 Every audit encompasses GAAS. An audit encompasses GAGAS as well as GAAS only when required by law, regulation, contract, agreement, policy or voluntary choice. An audit encompasses OMB Circular A-133 as well as GAAS and GAGAS when an organization has more than $500,000 of expenditures of federal financial assistance in their accounting year. Forms of federal financial assistance includes grants; cooperative agreements; donated surplus property; food commodities; loans; loan guarantees; property; interest subsidies; insurance; and direct appropriations. However, if an organization is determined to be a vendor versus a subrecipient, OMB Circular A-133 would not apply. For subsidy payments paid to child care providers, the provider is considered to be a vendor and, as a result, OMB Circular A-133 would not apply. The assistance may come as pass-through funds from state and local governments or another non-profit, or directly from the federal government. The complexion of the funds as federal does not change merely by passing through the “hands” of a non-federal entity. In some cases, the determination of the source of the funds is not clear from the grant agreement, particularly if the grant funds have passed through multiple recipients. The OMB has issued circulars to assist entities in administering the use of federal dollars. These circulars provide principles and standards of compliance for organizations awarded federal financial assistance. OMB Circular A-l22, Cost Principles for Not for Profit Organizations, establishes principles for determining applicable costs and covers the allowability and reasonableness of costs, cost allocation as well as the definition of direct and indirect costs. OMB Circular A-l10, Uniform Administration Requirements for Grants and Other Agreements with Institutions of Higher Education, Hospitals, and Other Not-for-Profit Organizations, establishes standards for the administration of federal financial assistance to organizations. 2-12 OTHER POTENTIAL AUDITS Funding agencies can also audit or monitor the activities of programs they fund. As a result, due to the number of potential parties who may be auditing or monitoring your program, it is imperative that your organization incorporate sound financial management. 2-13 CHAPTER 3 PRESCHOOL PROGRAMS AND FUNDING OBJECTIVES Review of the material will enable participants to become more familiar with the various types of funding available to Preschool programs as well as gain a greater understanding of the funds. The following program summaries are provided on the Office of Child Development and Early Learning’s website. Accountability Block Grant-Pre K (ABG) Child And Adult Care Food Program (CACFP) National School Lunch Program Title I — Improving The Academic Achievement Of The Disadvantaged Head Start Head Start Supplemental PA Pre-K Counts Keystone STARS Child Care Works Fees Child Care Private Fees District Funded Pre-K 3-1 The program summaries provide information related to the: Purpose of the funds Eligible providers Requirements related to family and child eligibility Means by which families can access services from a particular program Lead teacher qualifications and professional development, if applicable to a program Mandatory class size and staff/child ratios Reporting requirements of both the program and child/family Required curriculum Child assessment requirement, if any, for a program Reference to the regulations for a program Source of funding Major categories of allowable as well as unallowable expenses Financial reporting time lines Payment mechanisms to providers Fiscal year of the funding Whether parent fees are required or permitted How funds are allocated by the funding agency. 3-2 CHAPTER 4 COST ALLOCATION OBJECTIVES Review of the material in this chapter will enable participants to: A. Differentiate between direct and indirect costs Discuss when costs can be allocated Discuss various cost allocation methodologies COST ALLOCATION A cost is allocable to a particular cost objective (for example, a grant, contract, project, or service) in accordance with the relative benefits received. A cost is allocable to an award if it is treated consistently with other costs incurred for the same purpose in like circumstances and if it: Is incurred specifically for the award; Benefits both the award and other work and can be distributed in reasonable proportion to the benefits received, or Is necessary to the overall operation of the organization, although a direct relationship to any particular cost objective cannot be shown. Direct costs are those that can be identified specifically with a particular final cost objective (for example, a grant, contract, project, or service). Indirect costs are those that have been incurred for common objectives and cannot be readily identified with a particular final cost objective. Typical examples of indirect costs may include depreciation, operating and maintenance costs of a facility, and general and administrative costs, such as the salaries and expenses of the executive director and accounting. B. ALLOCATION OF INDIRECT COSTS Where an organization has only one major function, or where all major functions benefit from its indirect costs to approximately the same degree, the allocation of indirect costs may be accomplished using a single base, such as total direct costs. 4-1 Where an organization has several major functions which benefit from its indirect costs in varying degrees, allocation of indirect costs may require the accumulation of such costs into separate cost groupings which then are allocated individually to benefiting functions by means of a base which best measures the relative degree of benefit. For example, indirect salaries, payroll taxes, and benefits might be allocated based on full time equivalents, while occupancy related costs might be allocated based upon square footage of direct space utilized. EXAMPLE 4-1 An early learning classroom has 20 students. The total cost of the classroom is $100,000. Of the 20 students, 12 are funded by PA Pre K Counts, 6 by Head Start and 2 by CCIS. A reasonable allocation of cost could be based on the number of students. As a result, $60,000 of the total cost would be allocated to PA Pre K Counts ($100,000 X 12/20); $30,000 to Head Start ($100,000 X 6/20); and $10,000 to CCIS ($100,000 X 2/20). This assumes there are no direct costs to a particular funding stream. EXAMPLE 4-2 An early learning classroom has 20 students. The total cost of the classroom is $100,000. Included in the $100,000 is $10,000 of direct costs attributable to PA Pre K Counts. All other costs are considered indirect costs. Of the 20 students, 12 are funded by PA Pre K Counts, 6 by Head Start and 2 by CCIS. A reasonable rationale allocation of indirect cost could be based on the number of students. As a result, $54,000 of the total cost would be allocated to PA Pre K Counts ($ 90,000 X 12/20) as indirect cost and the $10,000 of direct costs would be added to the indirect costs arriving at a total cost of $64,000. In addition; $27,000 of indirect costs would be allocated to Head Start ($90,000 X 6/20); and $9,000 to CCIS ($90,000 X 2/20). EXAMPLE 4-3 An early learning center has three classrooms. Classrooms #1 and #2 each has 20 students, while Classroom #3 has 10 students. Each classroom is 450 square feet. The total cost of the three classrooms is $500,000, of which $60,000 is attributable to rent expense. The center has decided to allocate all expenses other than rent based upon the number of students, while the rent will be allocated based on square footage. As a result, Classroom 1 and 2 are each allocated $176,000 of the non-rent operating costs (20 students/50 students total X $440,000), while Classroom 3 is allocated $88,000 of the non-rent operating costs (10 students/50 students total X $440,000). The rent is allocated equally to each classroom since each is the same size. 4-2 As the above example illustrate, multiple methodology are available to an organization to allocate its costs, provided the methodology results in a reasonable, rationale allocation of costs based upon the benefits derived. Some examples of proper bases (drivers) to allocate costs are relative benefits derived, direct costs, direct salaries, square footage, or full time equivalents. Some examples of improper bases (drivers) are total funding by program or whether excess funds are available in a budget. 4-3 CHAPTER 5 WORKSHEETS AND GUIDELINES The Commonwealth of Pennsylvania’s Office of Child Development and Early Learning has developed the following version of a Braiding Funds Worksheet. The use of this worksheet is not required, but is extremely useful to organization demonstrate that cost have been allocated to the various funding streams in a reasonable, rationale manner. This worksheet is comprised of the following components: Facesheet – The facesheet documents the total funding at the agency level to be allocated across all budgets. To properly allocate costs, a user will need to list the same funding stream multiple times to account for different program hours or program year. Direct Salaries and Benefits – This form collects the salaries and benefits of the teachers and aides in each respective classroom. This worksheet then allocates the total salaries and benefits of the teachers and aides in the classroom to the respective funding source based upon the number of children in the classroom, the number of days per year for the respective funding sources as well as the hours per day. Program Distributed Charges – This form collects all other program expenses. This worksheet will distribute these charges to the respective funding sources based upon the same allocation method as the direct salaries and benefits mentioned immediately above. Administrative Distributed Charges – Use this form to enter all administrative and legal entity expenses. This worksheet will distribute these charges to the respective funding sources based upon the same allocation method as the direct salaries and benefits mentioned previously. Direct Program Charges – Use this form to enter any projected direct program expenses. Direct program expenses are allowable only if the program can make a strong justification as to why the expense should not be allocated to all programs. This information must be entered on the justification page which follows. Direct Program Charge Justification- This form documents the Organization’s case as to why certain expenses should be charged directly to a particular program as opposed to being spread among all funding sources. 5-1 CHAPTER 6 CASE STUDY USING THE COMMONWEALTH OF PENNSYLVANIA’S OFFICE OF CHILD DEVELOPMENT AND EARLY LEARNING’S VERSION OF A BRAIDING FUNDS WORKSHEET. OBJECTIVES Review of the material in this chapter will enable participants to: A. Understand the importance of cost allocation related to the various funding available to Pre-K providers Understand the braiding funds concept ESTABLISHING A COST ALLOCATION PLA Cost must be divided into two groupings: o o B. Program Administrative Costs must be consistently treated as either Program or Administrative Expenses are going to potentially be in both cost classifications. CASE STUDY OF THE ALLOCATION PROCESS DCAH, Inc. is in the process of allocating costs to its various funded programs. They have constructed a personnel cost worksheet, covering the proposed salaries and benefits of their staff. In addition, they have built into their worksheet the value of accumulated compensated absences to be carried over to a subsequent period. These absences will be paid or used in a subsequent period. Next, DCAH separated their personnel and other costs into those that, potentially, can be directly charged to a funded program. All other costs will be allocated. Next, DCAH’s management developed a schedule of classrooms, based upon available staff; number of students by funding source; classroom hours for funding sources as well as a calendar of total days by funding source. 6-1 The following is the relevant numerical data that has been collected based upon the above information in summarized form. (NOTE : THE FOLLOWING INFORMATION IS BEING USED FOR ILLUSTRATION PURPOSES ONLY AND IS NOT INTENDED TO BE A RECOMMENDED OR FACTUAL CASE—IT IS INTENDED SOLELY TO GIVE PARTICIPANTS AN OPPORTUNITY TO USE THE WORKSHEETS. PLEASE, DO NOT GET CONCERN ABOUT CERTAIN DATA WHICH IS CONTRARY TO WHAT MAY EXIST AT YOUR ORGANIZATION. AGAIN, THIS IS ONLY AN ILLUSTRATION AND IS NOT INTENDED TO REPRESENT A PRESCRIBED OR MODEL CLASSROOM, A MODEL CALENDAR, A RECOMMENED SALARY/BENEFITS PACKAGE, ETC.) Funding available: PA Pre K Counts $190,000 Head Start 140,000 Child Care Private Fees, which includes revenue from CCIS 85,000 Expenses that DCAH feels they can justify as being direct charges not subject to allocation: Professional Development Costs in Excess of 6 hours required by Child Care Private Fees funding: PA Pre K Counts $3,000 Head Start 2,000 Direct Salaries and Benefit Expenses Related to Teachers and Aides in the Three Classrooms Classroom 1: Teacher A: Salary $45,000 Benefits $13,500 Aide A: Salary $20,000 Benefits $ 8,000 Classroom 2: Teacher B: Salary $40,000 Benefits $12,000 Aide B: Salary $20,000 Benefits $ 8,000 Classroom 3: Teacher C: Salary $38,000 Benefits $11,400 Aide C: Salary $20,000 Benefits $ 8,000 6-2 Students by Funding Source by Classroom: Classroom 1: Pre K Counts 9; Head Start 9; Private 2 Classroom 2: Pre K Counts 15; Head Start 2; Private 3 Classroom 3: Pre K Counts 4; Head Start 13; Private 3 The calendar by funding source is summarized below: Pre K Counts 200 days/5 hours/day Head Start 180 days/5 hours/day Private 260/4 hours/day Program Distributed Charges total $60,000 Administrative Distributive Charges total $112,000 Using the above information, attempt to complete the sample worksheet. 6-3 APPENDIX A Definitions of Terms Used in this Workbook The following terms were presented in this manual. inclusive. Obviously, this list is not all- Accounting equation – [Assets = liabilities + net assets] is the basis for the statement of financial position, also called the balance sheet. Accounts payable - A/P, the bills your organization owes to suppliers. Accounts receivable - A/R, the amounts owed to you by your customers. Accrual method of accounting - record income when earned, not when payment is received. For expenses, record when goods or services are received, not when they are paid. Adjusting entries - entries necessary to update accounts for items that are not recorded in daily transactions, which are made when books are closed at the end of an accounting period. Aging report - list of accounts receivable amounts and their due dates, used to alert management to slow-paying customers. Also, for accounts payable to assist in managing outstanding bills. Allowance for bad debts- reserve for bad debts is an estimate of uncollectable accounts receivables. Assets - things of value held by the organization, such as cash, accounts receivable, furniture and fixtures, and certain intangibles. Balance sheet - statement of financial position that provides a financial "snapshot" of your organization at a given point in time. It lists an organization’s assets, liabilities, and equity. Change in Net Assets – the difference between revenue and expenses. Cash method of accounting - record income only when cash is received from customers. For expenses, record only when checks are written to the vendor. Chart of accounts - list of account titles used in your accounting records. Closing the books - the procedures that take place at the end of an accounting period. Adjusting entries are made, and then the revenue and gains and expense and loss accounts are "closed." The change in net assets (revenues and gains minus expenses and losses) that results from the closing is transferred to an equity account (net assets). A-1 Credit memo - Writing off all or part of a customer's account receivable balance. Credits - At least one component of every accounting transaction (journal entry) is a credit. Credits increase liabilities and net assets and decrease assets. Current assets - assets that are in the form of cash or will generally be converted to cash or used up within one year. Examples are accounts receivable and inventory. Current liabilities - Liabilities payable within one year. Examples are accounts payable and payroll taxes payable. Current ratio – current assets divided by current liabilities. It represents a measure of liquidity. The result should be are less 1.00; otherwise, an entity does not have sufficient current assets to meet its current obligations. Debit memo - Billing a customer again. Debits - At least one component of every accounting transaction (journal entry) is a debit. Debits increase assets and decrease liabilities and net assets. Depreciation expense - a procedure to annually write-off a portion of the cost of fixed assets, such as vehicles and equipment. Double-entry accounting - every transaction has at least two entries: a debit and a credit. Debits must always equal credits. Double-entry accounting is the basis of a true accounting system. Expense accounts - the accounts used to keep track of the costs of doing business, such as wages, payroll taxes, and rent. Fixed assets - Assets that have a useful life of more than one year and exceed the organization’s capitalization threshold, such as equipment and vehicles. Foot - to total the amounts in a column, such as a column in a journal or a ledger. General ledger- the collection of all balance sheet, revenue, gains, expense, and loss accounts used to keep the accounting records of an organization. Indirect costs -those costs that have been incurred for common objectives and cannot be readily identified with a particular final cost objective. Examples are rent, office supplies, and administrative salaries. Journal - the chronological listing of transactions of an organization that are recorded in sales, cash receipts, and cash disbursements journals. A general journal is used to enter period end adjusting and closing entries and other special transactions not entered in the other journals. A-2 Liabilities - what your organization owes creditors, such as accounts payable, payroll taxes payable and accrued payroll. Long-term liabilities - liabilities that are not due within one year, such as notes payables. Net assets - accumulated change in net assets of the organization. Post - to summarize all entries and transfer them to the general ledger accounts. Prepaid expenses - Amounts paid in advance to a vendor or creditor for goods or services, which is actually an asset of your organization since your vendor or supplier owes your organization the goods or services. An example would be the unexpired portion of an annual insurance premium. Statement of Activities - an income statement or "P&L." that lists an organization’s revenues, gains, expenses, losses, and change in net assets (profit or loss). Trend analysis – comparison of information from one period to another. For example, comparing expense for the current year to that of a prior year. Trial balance - prepared at the end of an accounting period by listing all the accounts with their associated balances in the general ledger. The debit balances equal the credit balances. Unearned revenue- deferred revenue or prepaid income represents money received in advance of providing a service to your customer. It is a liability of your organization since you still owe the service to the customer. An example would be an advance payment to your organization for some services your organization will be required to perform in the future. Variance Analysis- reviewing information when a deviation from some standard exist, such as reviewing expenses that are significantly different from the budgeted amount. A-3 RESOURCES National Association of Education for Young Children: Glossary of Financing Termshttp://www.naeyc.org/ece/critical/financing_glossary.asp U.S Department of Health and Human Services- Administration for Children and Families: Fiscal Glossary http://eclkc.ohs.acf.hhs.gov/hslc/Program%20Design%20and%20Management/Fiscal/Fi scal%20Glossary Office of Management and Budget Circulars http://www.whitehouse.gov/omb/circulars/