Name

advertisement

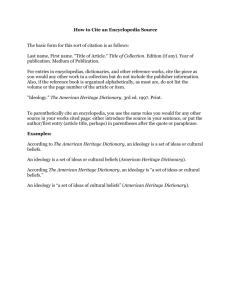

Name: ____________________________ English 10A Date: ____________________ Mrs. Mason Plagiarism/Paraphrasing The following information was taken directly from Harvard Guide to Using Sources. Verbatim Plagiarism If you copy language word for word from another source and use that language in your paper, you are plagiarizing verbatim. Even if you write down your own ideas in your own words and place them around text that you’ve drawn directly from a source, you must give credit to the author of the source material, either by placing the source material in quotation marks and providing a clear citation, or by paraphrasing the source material and providing a clear citation. Mosaic Plagiarism If you copy bits and pieces from a source (or several sources), changing a few words here and there without either adequately paraphrasing or quoting directly, the result is mosaic plagiarism. You are responsible for making clear distinctions between your ideas and the ideas of the scholars who have informed your work. Inadequate Paraphrase When you paraphrase, your task is to distill the source’s ideas in your own words. It’s not enough to change a few words here and there and leave the rest; instead, you must completely restate the ideas in the passage in your own words. If your own language is too close to the original, then you are plagiarizing, even if you do provide a citation. In order to make sure that you are using your own words, it’s a good idea to put away the source material while you write your paraphrase of it. This way, you will force yourself to distill the point you think the author is making and articulate it in a new way. Once you have done this, you should look back at the original and make sure that you have not used the same words or sentence structure. If you do want to use some of the author’s words for emphasis or clarity, you must put those words in quotation marks and provide a citation. Uncited Paraphrase When you use your own language to describe someone else’s idea, that idea still belongs to the author of the original material. Therefore, it’s not enough to paraphrase the source material responsibly; you also need to cite the source, even if you have changed the wording significantly. As with quoting, when you paraphrase you are offering your reader a glimpse of someone else’s work on your chosen topic, and you should also provide enough information for your reader to trace that work back to its original form. The rule of thumb here is simple: Whenever you use ideas that you did not think up yourself, you need to give credit to the source in which you found them, whether you quote directly from that material or provide a responsible paraphrase. Uncited Quotation When you put source material in quotation marks in your essay, you are telling your reader that you have drawn that material from somewhere else. But it’s not enough to indicate that the material in quotation marks is not the product of your own thinking: You must also credit the author of that material and provide a trail for your reader to follow back to the original document. This way, your reader will know who did the original work and will also be able to go back and consult that work if he or she is interested in learning more about the topic. Citations should always go directly after quotations. For examples and further explanation, go to http://usingsources.fas.harvard.edu/icb/icb.do?keyword=k70847&pageid=icb.page342054. The following information was taken directly from Harvard Guide to Using Sources. Common Knowledge The only source material that you can use in an essay without attribution is material that is considered common knowledge and is therefore not attributable to one source. Common knowledge is information generally known to an educated reader, such as widely known facts and dates, and, more rarely, ideas or language. Facts, ideas, and language that are distinct and unique products of a particular individual’s work do not count as common knowledge and must always be cited. Figuring out whether something is common knowledge can be tricky, and it’s always better to cite a source if you’re not sure whether the information or idea is common knowledge. If you err on the side of caution, the worst outcome would be that an instructor would tell you that you didn’t need to cite; if you don’t cite, you could end up with a larger problem. If you have encountered the information in multiple sources but still think you should cite it, cite the source you used that you think is most reliable, or the one that has shaped your thinking the most. For examples and further explanation, go to http://usingsources.fas.harvard.edu/icb/icb.do?keyword=k70847&pageid=icb.page342055. The following information was taken directly from Harvard Guide to Using Sources. Misrepresenting a Source When you use someone else’s ideas in your writing, you are expected to represent those ideas clearly and accurately. If you don’t understand something you’ve read, don’t try to incorporate it into your essay. If you try to incorporate ideas that you don’t understand, you run the risk of taking those ideas out of context or making the case that an author says something other than what he or she has actually said. In addition, if you don’t understand a source, you are more likely to blur the distinction between the source ideas and your own, which could lead you to unintentional plagiarism. The best way to prevent this is to make sure that you understand every idea that you are using in your paper, and to talk to your instructor about areas of confusion. For examples and further explanation, go to http://usingsources.fas.harvard.edu/icb/icb.do?keyword=k70847&pageid=icb.page355346. The following information was taken directly from Harvard Guide to Using Sources. When to Summarize, Paraphrase, and Use Quotes When you summarize, you provide your readers with a condensed version of an author’s key points. A summary can be as short as a few sentences or much longer, depending on the complexity of the text and the level of detail you wish to provide to your readers. [When you include a summary in your paper, you must cite the source.] When you paraphrase from a source, you restate the source’s ideas in your own words. Whereas a summary provides your readers with a condensed overview of a source (or part of a source), a paraphrase of a source offers your readers the same level of detail provided in the original source. Therefore, while a summary will be shorter than the original source material, a paraphrase will generally be about the same length as the original source material. [When you include a paraphrase in your paper, you must cite the source.] [When you quote from a source,] you should only quote directly from a text when it’s important for your reader to see the actual language used by the author of the source. For examples and further explanation, go to http://usingsources.fas.harvard.edu/icb/icb.do?keyword=k70847&pageid=icb.page350378. The information in quotes was taken directly from Harvard Guide to Using Sources. Parenthetical Citations Parenthetical citation: to credit a source and to alert the reader to find the source on the works cited Parenthetical citations MUST BE PRESENT for ALL research used in your report; every detailed summarized, quoted, or paraphrased must have a parenthetical citation. Parenthetical citations for different circumstances 1. When citing two articles by the same author, list the last name of the author first and the abbreviated version of the title. Example: (Smith, “Pollution…”). 2. If no author is listed, use the article title or whatever comes next on the works cited page. Example: (“The Mississippi” 41) 3. If there is no page number and for Internet sources, use the author’s name or whatever comes first on the works cited page. Example: (Straub) 4. “To attribute a point to multiple sources, list them together in one parenthetical citation, separated by semicolons. Include page numbers if you refer to specific pages in each work.” Example: (Adams; Dryer; White) 5. When citing sources “by multiple authors with the same last name, use the first initial and last name or, if necessary, first and last name.” Example: (C. White) Tips to Remember for In-text Citations Include the last name of the author and the page number where you found the information in your citation. For Internet sources, do not include page numbers. If there is no author listed, use the title of the work. Do not put a comma between the author’s last name or article title and the page number. “If the text of your paper makes it clear that you are referring to a particular work, there is no need to repeat the author’s name in a parenthetical citation; instead, you can cite the page number(s) only.” Include the citation immediately after the reference, regardless of where it falls in the sentence. Put commas and end punctuation after the closing parenthesis. If you use material that is already quoted within your source, use single quotes within the double quotes. The information in quotes was taken directly from Harvard Guide to Using Sources. Works Cited Page Order of information needs to be in alphabetical order. Make sure you include periods, commas, and quotation marks, etc. in the appropriate places. Indent the subsequent lines for each source. <web address>. Only include the sources that you actually used in your paper. “When you list two works by the same author, you do not need to list the author a second time. Instead, use three dashes to indicate the second reference to the author.” Example of a Works Cited Page Works Cited Dale, Youngbee. “Chinese Cannibalism of Infant Flesh Outrages the World.” The Washington Post. n.p. 10 March 2012. Web. 4 March 2014. <http://communities.washingtontimes.com/neighborhood/rights-sodivine/2012/may/10/chinese-cannibalism-infant-flesh-outrages-world/>. ---. “Has China’s One-Child Policy worked?” BBC News. n.p. 20 September 2007. Web. 4 March 2014. <http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/7000931.stm>. “Iranian People Vote for an Islamic Republic.” Government, Politics, and Protest: Essential Primary Sources. Ed. K. Lee Lerner, Brenda Wilmoth Lerner, and Adrienne Wilmoth Lerner. Detroit: Gale, 2006. 278-280. World History in Context. Web. 5 March 2014. “Women, Men, and Gender in Islam.” The Muslim Almanac: A Reference Work on the History, Faith, Culture, and Peoples of Islam. Azim Nanji. Detroit: Gale Research, 1996. World History in Context. Web. 5 March 2014.