Looking for Atlantis

advertisement

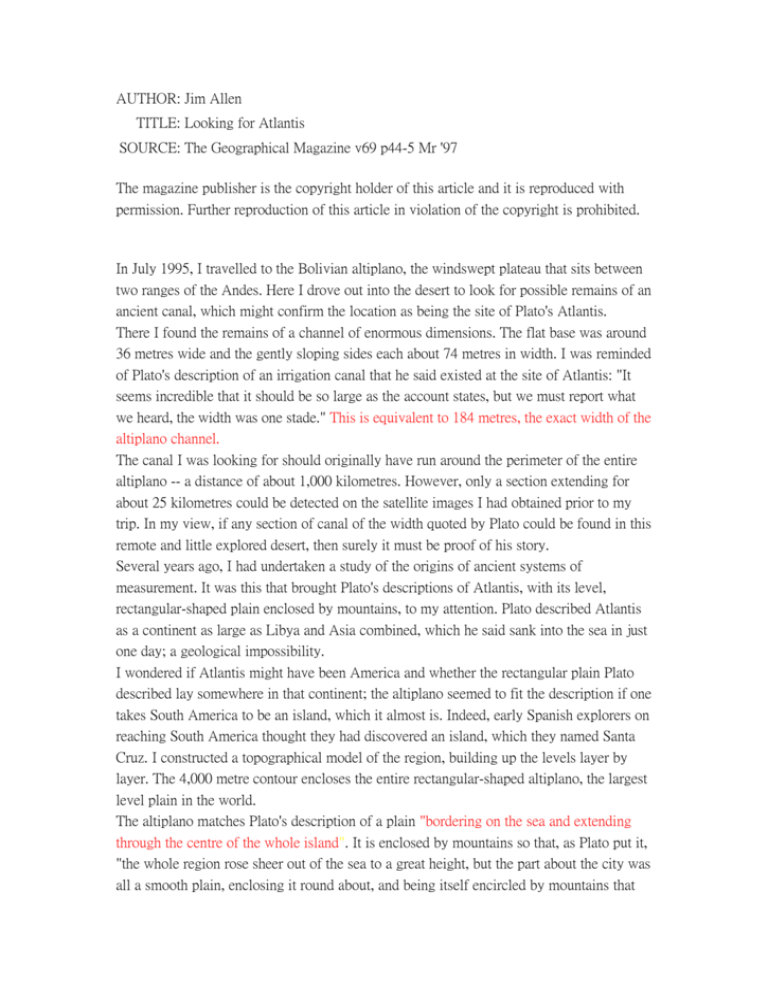

AUTHOR: Jim Allen TITLE: Looking for Atlantis SOURCE: The Geographical Magazine v69 p44-5 Mr '97 The magazine publisher is the copyright holder of this article and it is reproduced with permission. Further reproduction of this article in violation of the copyright is prohibited. In July 1995, I travelled to the Bolivian altiplano, the windswept plateau that sits between two ranges of the Andes. Here I drove out into the desert to look for possible remains of an ancient canal, which might confirm the location as being the site of Plato's Atlantis. There I found the remains of a channel of enormous dimensions. The flat base was around 36 metres wide and the gently sloping sides each about 74 metres in width. I was reminded of Plato's description of an irrigation canal that he said existed at the site of Atlantis: "It seems incredible that it should be so large as the account states, but we must report what we heard, the width was one stade." This is equivalent to 184 metres, the exact width of the altiplano channel. The canal I was looking for should originally have run around the perimeter of the entire altiplano -- a distance of about 1,000 kilometres. However, only a section extending for about 25 kilometres could be detected on the satellite images I had obtained prior to my trip. In my view, if any section of canal of the width quoted by Plato could be found in this remote and little explored desert, then surely it must be proof of his story. Several years ago, I had undertaken a study of the origins of ancient systems of measurement. It was this that brought Plato's descriptions of Atlantis, with its level, rectangular-shaped plain enclosed by mountains, to my attention. Plato described Atlantis as a continent as large as Libya and Asia combined, which he said sank into the sea in just one day; a geological impossibility. I wondered if Atlantis might have been America and whether the rectangular plain Plato described lay somewhere in that continent; the altiplano seemed to fit the description if one takes South America to be an island, which it almost is. Indeed, early Spanish explorers on reaching South America thought they had discovered an island, which they named Santa Cruz. I constructed a topographical model of the region, building up the levels layer by layer. The 4,000 metre contour encloses the entire rectangular-shaped altiplano, the largest level plain in the world. The altiplano matches Plato's description of a plain "bordering on the sea and extending through the centre of the whole island". It is enclosed by mountains so that, as Plato put it, "the whole region rose sheer out of the sea to a great height, but the part about the city was all a smooth plain, enclosing it round about, and being itself encircled by mountains that stretched as far as the sea." What if it was not the island continent of Atlantis that sank into the sea as Plato believed, but only the island city of Atlantis, built around the lava rings of an extinct or dormant volcano, which sank beneath an inland sea, or what is now Lake Poopó? The city could only have sunk into such a body of water, as it lay upon a plain "high above the level of the sea". The island city was surrounded by concentric rings of water and land, the rings of water being connected to the sea by means of an artificial channel. The walls of this ancient city were plated in gold, silver, bronze, tin and a mysterious metal called "orichalcum", which could be polished to "sparkle like red fire". All these metals are found around Lake Poopó. Numerous gold and copper mines still exist there; the silver-rich mountain of Potosí was a great source of wealth for the Spanish empire and is still a major source of tin. Even the unknown orichalcum is found here; it is a natural alloy of gold and copper found only in the Andes. The continent that Plato called Atlantis could well be that which we now call South America. At the time of the Spanish conquest, the Inca called it 'Tahuantinsuyo', meaning 'land of the four quarters'. Their capital was at Cuzco, some 350 kilometres north of Lake Titicaca, in what is now Peru. The quarter of their empire running along the Andes, east of Cuzco, was called 'Antisuyo' and was home to the ferocious Antis Indians. In their native language, 'atl' means water and 'antis' means copper; could this be the origin of the name Atlantis? During the wet season, from December to March, the altiplano floods. The south of the the plain suffers drought conditions for the rest of the year. The contours of the altiplano are such that it would have been feasible to construct a perimeter canal, like the one Plato described, which would drain water away during the wet season and provide water for irrigation during times of drought. The altiplano is an enclosed basin and a period of torrential rain could produce within it an inland sea such as that which existed from 38,000BC to 23,000BC (known as Lake Minchin) and again in 9000BC, when the plain was submerged beneath 60 metres of water for about 1,000 years. If we reexamine Plato's statement about the end of Atlantis, such an event is described as occurring as a result of earthquakes and floods, in a single day and night of rain. And the altiplano is an area prone to earthquakes. Plato gives a date for the end of Atlantis as being around 9600BC. At this time, the altiplano was indeed flooded. However, he also said that the end took place at a time when the confederation of Atlantis was engaged in a war against Egypt. Should the years be in fact lunar months, then this could correspond to the attacks on Egypt made by the Sea Peoples, or "the Peoples from the Isles in the midst of the sea". These people were defeated, it is written, by Ramesses III in about 1200BC. Many of the invaders were taken prisoners and some entered the service of the king. It seems possible that the story of Atlantis came from one of these people, and was handed on by temple priests to the visiting Greek statesman Solon, which is, after all what Plato claimed. Added material Jim Allen is a former cartographic draughtsman and air photo interpreter. He has prepared a 176-page illustrated book on his theory GARY HALEY The lost city of Atlantis as portrayed by Thomas Cole (1801-48) THE BRIDGEMAN ART LIBRARY An aerial photo provides evidence of a section of canal in the Bolivian altiplano of the width quoted by Plato A LEGEND OF A CITY In Plato's story, written about 380BC, he describes Atlantis as an island continent which had existed in the Atlantic Ocean, but which sank into the sea in the space of a single day and night. In his detailed geographic description, he tells of a rectangular level plain lying in the centre of a continent, next to the sea and midway along its longest side. The plain was high above the level of the sea and enclosed by mountains. Near the centre of the plain was a volcanic mound with concentric rings of sea and land enclosing a central island. On this island lay the Royal City of Atlantis. A canal was excavated to the nearby sea to allow the rings of water to be used as harbours by this great commercial society. The walls of the city were plated in gold, silver, bronze, tin and an exotic alloy called orichalcum. The end of the city was brought about at a time of violent earthquakes and floods, when it was "swallowed up by the sea and vanished". Source: Plato IX, Timaeus, Critias, translated by RG Bury (LOEB Classical Library). Alternative translation: Desmond Lee (Penguin Classics). GOING THERE When to go: December to March is the wet season. Most of the year the southern altiplano is windswept, sunny in the day and freezing at night. July and August is the best season. Getting there: There are no direct flights to Bolivia. American Airlines (Tel: 0345 789789) offers the simplest route from London Heathrow to La Paz via Miami. British Airways (Tel: 0345 222111) flies from Heathrow to La Paz. Visa requirements: British citizens do not require a visa for a stay of up to 90 days. Further information: Journey Latin America runs a three day tour of the altiplano (Tel: 0181 747 8315). Useful books include Bolivia travel survival kit (Lonely Planet, £12.99) and South American Handbook (Footprint Handbooks, £21.99). WBN: 9706003134012 http://vnweb.hwwilsonweb.com/hww/results/results_single_fulltext.jhtml;hwwilsonid =FJ1PNCZHGH0I3QA3DINCFF4ADUNGIIV0