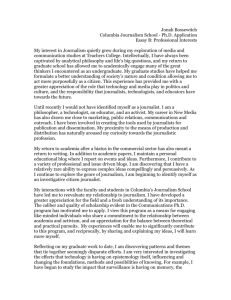

School of Media and Communication

advertisement