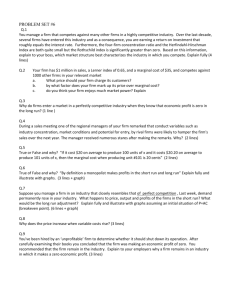

double_marginalization

advertisement

The theory of double marginalization, also known as the problem of successive monopoly, was independently developed by Cournot (1838) and Ellet (1839). Spengler (1950) is the classic reference for double marginalization in the vertical integration context (i.e., where the two monopolists and a final good producer and its supplier). Since Spengler was published in English before Cournot and Ellet, sometimes he is cited as originating the idea. The problem of double marginalization occurs when two firms independently set prices for complementary goods. This framework can be used in both the case of traditional complements (e.g., tea and sugar) and in the case of a vertical relationship (e.g., where the complementary goods are a manufactured good and the retail service whereby the good is sold). Consider two monopolists who produce complementary products. If they independently set prices (or quantities), then the prices chosen would be higher then those chosen by a merged firm, since each firm ignores the negative externality of its price on the profits of the other firm. If this effect is particularly strong, it can lead the merged firm to set price below marginal cost for one of the two products. Note that this effect does not require perfect monopoly. Both firms must have some market power (more specifically, they must have the ability to price above marginal cost and earn positive profits). If one of the two firms lacked any market power, then they would not be earning any profits, and the pricing of the other firm would have no negative externality on that firm (at least in the long run). Thus, double marginalization requires some market power by both firms, but not necessarily a full monopoly. Nor does the double marginalization effect require perfect complementarity between the two goods. As long as prices of each firm exert a negative externality on the profits of the other firm, this effect will hold. The double marginalization effect is closely related to the normal effect whereby horizontal mergers raise prices. In the case of horizontal mergers, the goods are substitutes. This means that the price of one firm exerts a positive externality on the other firms (a higher price for my competitor’s product means more profits for me). Thus, when horizontal competitors set prices independently, they price too low, relative to the prices that would maximize their total profits. When these firms merge, collude, or otherwise find a way to internalize this externality, they raise prices. The exact opposite happens in the case when the goods are complements. The externality is negative (a higher price for a complement means less profit for me), which means that independent pricing results in prices that are too low relative to the prices that maximize collective profits. Thus, when producers of complements merge, collude, or otherwise find a way to internalize this externality, they lower prices, resulting in a Pareto improvement (since consumers also prefer lower prices). The double marginalization problem can be solved in a number of different ways. I have already mentioned collusion (which could be implemented by a contract specifying a maximum resale price, which may or may not be legal under U.S. antitrust laws) and vertical mergers as two possibilities. A third possibility involves the use of franchise fees. This is easiest to see in the case where the two firms are monopolies in a vertical relationship (an upstream monopoly and a downstream monopoly). The upstream firm could charge its marginal cost to the downstream firm, and allow the downstream firm to extract the full monopoly profit. In return, the downstream firm would pay the upstream firm a lump sum franchise fee. This allows the upstream firm to capture a share of the monopoly profit, while effectively eliminating the double marginalization problem (since, conditional on one firm charging marginal cost, the other firm maximizes joint profits when it prices independently). Which solution is best will depend on industry details that go beyond the basic concern of double marginalization. In more general models, there may be asymmetric information, incomplete contracts, antitrust laws, and other externalities, and all of these issues will be affected by the regime chosen for jointly determining prices. Thus, the optimal choice of a strategy for dealing with double marginalization will have to consider the effect alleviating or aggravating other problems. References Cournot, A. (ed.) (1838 originally, 1971 English translation), Mathematical Principals of the Theory of Wealth. August M. Kelly, New York, Chapter IX. Ellet (1839 originally, 1966 English translation), An Essay on the Laws of Trade. Augustus M. Kelly, New York, pp. 77-80. Spengler, J.J. (1950), “Vertical Integration and Antitrust Policy,” Journal of Political Economy, pp. 347-352.