introduction - European Union Center of Excellence

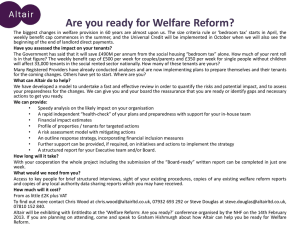

advertisement