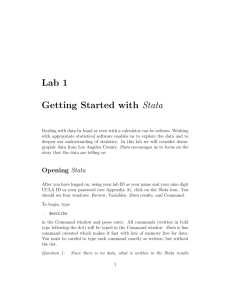

in Stata

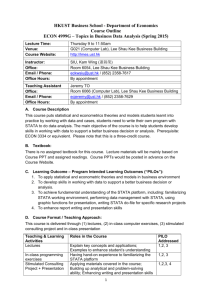

advertisement

Washington & Lee’s Guide to Stata Niels-Hugo Blunch and Carol Hansen Karsch Table of Contents Stata Resources...........................................................................................................................................................1 Components of Stata: .................................................................................................................................................1 Stata Basics: ...............................................................................................................................................................2 Opening a Stata File ...........................................................................................................................................2 . use .............................................................................................................................................................2 . set memory................................................................................................................................................2 Command Syntax ...............................................................................................................................................2 Making Stata Stop ..............................................................................................................................................3 Restricting the Data ............................................................................................................................................3 “Help” in Stata ....................................................................................................................................................3 Interactive vs. Batch Mode .........................................................................................................................................4 Interactive Mode .................................................................................................................................................4 Batch Mode Using Do Files ...............................................................................................................................4 Best of Both Approach .......................................................................................................................................4 Documenting A Stata Session – The Log - File: ...............................................................................................4 Importing Data into Stata: ..........................................................................................................................................5 Examining the Data ....................................................................................................................................................6 . describe .............................................................................................................................................................6 . summarize varname, detail ...............................................................................................................................6 . codebook varname ............................................................................................................................................6 . tabulate varname ...............................................................................................................................................7 . tabulate varone vartwo......................................................................................................................................8 . tabstat varone vartwo, etc. ................................................................................................................................8 . histogram varname ...........................................................................................................................................9 . graph box varname ...........................................................................................................................................9 . tsline varname .................................................................................................................................................11 Verifying the Data ....................................................................................................................................................12 . assert ...............................................................................................................................................................12 Numeric Missing Values ..................................................................................................................................12 . correlate - Checking For Correlation ..............................................................................................................13 Creating & Modifying Variables ..............................................................................................................................14 CREATING NEW VARIABLES....................................................................................................................14 Variable Names: .......................................................................................................................................14 i = Versus == ..............................................................................................................................................14 . generate...........................................................................................................................................................14 Addition/Subraction ..................................................................................................................................14 Division /Multiplication (Interaction) .......................................................................................................14 Exponentiation ..........................................................................................................................................14 Lag ............................................................................................................................................................15 Log: ...........................................................................................................................................................15 . egen.................................................................................................................................................................15 Dummy Variables .............................................................................................................................................15 The Easy Way ...........................................................................................................................................15 Second Method .........................................................................................................................................16 Third Method ............................................................................................................................................16 Dates .................................................................................................................................................................17 MODIFYING VARIABLES ............................................................................................................................17 String Variables ........................................................................................................................................17 . destring ...................................................................................................................................................17 . replace .....................................................................................................................................................18 . recode ......................................................................................................................................................18 Modifying and Combining Files ..............................................................................................................................19 Modifying a File ...............................................................................................................................................19 . keep & . drop ..........................................................................................................................................19 . move & . order : reordering the list of variables .....................................................................................19 . sort ..........................................................................................................................................................19 . reshape (wide long or long wide) ..................................................................................................20 Combining Files ...............................................................................................................................................21 . append .....................................................................................................................................................21 . merge ......................................................................................................................................................21 Time Series and Panel Data ..............................................................................................................................22 Time Series Operators ..............................................................................................................................23 Regression Analysis .................................................................................................................................................24 OLS (Studenmund, pp. 35 – 40) .......................................................................................................................24 Restricting Stata commands to observations with certain conditions satisfied.........................................24 Ensuring Consistency Among the Number of Observations in the various estimation samples ..............24 Ramsey’s Regression Specification Error Test (RESET) (Studenmund, pp. 198 - 201) ..........................25 ii Akaike’s Information Criterion and the Schwartz (Bayesian Information) Criterion (Studenmund, p. 201) ...........................................................................................................................................................25 Detection of Multicollinearity: Variance Inflation Factors (Studenmund, p. 259) ...................................25 Serial Correlation ..............................................................................................................................................25 Durbin-Watson D Test for First-Order Autocorrelation (Studenmund, p. 325) ........................................25 Dealing With Autocorrelation ..................................................................................................................26 GLS Using Cochrane-Orcutt Method (Studenmund, p. 332) ...................................................................26 Newey-West standard errors (Studenmund, p. 334) .................................................................................26 Heteroskedasticity ............................................................................................................................................26 White test (Studenmund, p. 360) .............................................................................................................26 Weighted-Least Squares (WLS) (Studenmund, p. 363) ...........................................................................26 Heteroskedasticity-corrected (HC) standard errors (Studenmund, p. 365) ...............................................26 Hypothesis Testing ...................................................................................................................................................27 t-tests.................................................................................................................................................................27 f-tests ................................................................................................................................................................27 Tests for joint statistical significance of explanatory variables ................................................................27 Testing for equality of coefficients ...........................................................................................................27 Making “Nice” Tables of Regression Results ..........................................................................................................28 . outreg2 ............................................................................................................................................................28 The “estimates store” and “estimates table” Commands: .................................................................................28 More Advanced Regression Models ........................................................................................................................30 . logit & . probit models ...................................................................................................................................30 Probit with marginal effects reported .......................................................................................................30 Logit with marginal effects reported.........................................................................................................30 Multinomial logit ......................................................................................................................................30 Appendix A ..............................................................................................................................................................32 Do File Example ...............................................................................................................................................32 Appendix B ..............................................................................................................................................................33 Importing an Excel file into Stata .....................................................................................................................33 Appendix C ..............................................................................................................................................................34 Downloading Data from ICPSR .......................................................................................................................34 Using a Stata Setup File to Import ASCII Data into Stata................................................................................35 iii STATA RESOURCES Stata’s own website is the natural starting place – the following link leads you to a wealth of info on Stata, including Tutorials, FAQs, and textbooks: http://www.stata.com/links/resources.html One of the most helpful links found on the Stata site is UCLA’s Stata Resources website. It includes a set of learning modules: http://www.ats.ucla.edu/stat/stata/modules/default.htm COMPONENTS OF STATA: Stata opens several windows when it launches. A window can be opened and made active either by clicking on it with the mouse or by selecting it from the “Window” menu. Right-clicking on a window displays options for that window. 1) Results are displayed in the Results window. 2) Commands are entered into the command line from the Command window. 3) Previously entered commands are displayed in the Review window. 4) The variables for the current dataset are displayed in the Variables window. a) The Variables window can be used to enter variable names into the Command window (simply click on a variable name) b) In version 10 of Stata, right clicking on a variable in the window gives the options to rename, create or edit a label, or change a variable’s format. The Stata toolbar provides access to commonly used features: 1) Holding the mouse pointer over a button displays a description of the button. 2) A window can be opened by clicking its button on the toolbar. Menus and dialogs can provide access to commands in Stata until the time comes when you want to directly enter the command in the command window. The working directory is displayed on the status bar in the lower left-hand corner. 1 STATA BASICS: Stata is case sensitive. Commands are written in lower-case. Variable and file names can be in upper and/or lower case, but consistency is necessary. Stata interprets GDP and gdp as two different variables that can co-exist in the same file. OPENING A STATA FILE . use The easiest way to open a Stata file is to double click on it in the directory. If you are already in the program, the the menu system is the next easiest: click on the File menu, select Open and then browse to your file. Alternatively, type the command: . use filename in the command window or in a batch file. A file cannot be opened when another file is already open. Either close the first file or use the replace option in the . use command. . use filename, replace . set memory Stata tries to load an entire file into memory. A problem will arise if you try to open a large file and insufficient memory has been allocated to the program. You’ll get an error message that states that there is “no room to add observations.” To assign more memory to Stata, use the . set memory command. For computers on campus, you could easily set memory to 300m or 300000k, maybe more, if necessary. Then use the menu system or the . use command to open the file from within that copy of the Stata program. Do NOT double click on the file in the directory. That launches another copy of the Stata program with the default amount of memory allocated to it, and you’ll get the error message again. It is just like having two copies of MS Word or Excel open, one with the default memory and one with the increased amount of memory. COMMAND SYNTAX Stata commands have a common syntax, which is written in the following manner: . prefix_cmd: command varlist if exp in range, options In a lot of Stata documentation, commands are preceded by a “.” and that convention will be followed in this guide. Do NOT type the period!!!! Commands can be extremely simple: . list will cause Stata to list the entire file. No need to use a menu to issue that command! Obviously, commands can be more complex and powerful. Following the standard syntax, the list command illustrated below, (abbreviated to just . l), instructs Stata to list only the mpg, price and weight variables, if the price is greater than 20,000 in observations 1 through 100 by groups based on the values of the variable rep78. The option “clean” instructs the program to list the observations without boxes around each variables which makes the listing nice and compact. . by rep78: l mpg price weight if price > 20000 in 1/100, clean By default, observations are listed a screen full at a time. To get to the next screen of results, click on the blue – more – command that appears at the end of each screen. To change the default setting to get an uninterrupted flow of results, type in the command: 2 . set more off To switch back to the default of one screen full of output at a time, use the command: . set more on. MAKING STATA STOP To stop the output, whether streaming or paused at a - more - prompt, click on the break button, the red circle with the white “X”, located in the toolbar under the Help menu. RESTRICTING THE DATA The if and in qualifiers are extremely useful and work with many commands. They are used to restrict the operation of a command to observations that meet the specified conditions. In the example above, the . list command was restricted to observations with vehicles whose prices exceeded $20,000 within the first 100 observations. The results were also restricted to include only the variables contained in the varlist (mpg, price and weight.) Other variables in the dataset would not appear in the resulting list. For more examples of using the if qualifier, especially in regression models, see: “Restricting Stata commands to observations with certain conditions satisfied” in the “Regression Analysis” section. A typical example of a prefix_cmd is by which can be used to divide the data up into groups. “HELP” IN STATA Stata’s “Help” utility is very good. Use it to see how to use commands. Issuing the command ". help <XXXXXX>", for example, ". help summarize", will make Stata search through all the official Stata files. Descriptions will use the common Stata syntax described above. Alternatively issuing the command ". findit <XXXXXX>", will make Stata search the Web in addition to the official Stata files. This is particularly useful if searching for a keyword, concept and/or a Stata command that is NOT part of official Stata (there are many user-written Stata commands on the Web that can be downloaded into official Stata this way, by following the appropriate links resulting from the search.) 3 INTERACTIVE VS. BATCH MODE INTERACTIVE MODE In interactive mode, commands are typed “as you go” into the command window. The drawback is that when you end your Stata session, all your work is gone… (EXCEPT if you created a “log-file,” see below.) BATCH MODE USING DO FILES In batch mode, commands are written and saved as do files. Type the Stata commands directly into the “New Dofile Editor” (the fifth-from-last icon on the toolbar,) one command per line, the same way you would have done in interactive mode. Then SAVE the file before running it by clicking the “Do current do-file” button in the Do-file Editor. Advantages of using do files include: 1) Reproduce results exactly – and fast!! 2) Continue analyses from the point where you left off. 3) Recall your reasoning. Comments in do-files serve as memory aids, which can be useful six months later or as documentation for others trying to understand your work. Enclose multiple lines of comments by beginning the line with a "/*" and closing with a "*/". A single comment line can begin with a “*” or a “//”. The “//” can also be used to include comments on the same line as a command. Examples of all three types of comment codes are illustrated in the sample do file in Appendix A. BEST OF BOTH APPROACH Alternatively, combine the interactive and batch modes. Figure out the commands while working in interactive mode, then copy the error-free commands from the Results or Command windows and paste them into the Do-file Editor. This approach takes discipline. It can be hard to make yourself stop and do this bit of housekeeping, but it is usually time extremely well spent. So, it is highly recommended. DOCUMENTING A STATA SESSION – THE LOG - FILE: As explained above, do-files; except for initial, exploratory work; are the best way to document your work because results can always be replicated, and they serve as documentation of your Stata session. There is a possibility of documenting your entire Stata session, however, no matter whether you work in interactive or batch mode – this is the so called “log-file,” which is a file containing everything you did in your Stata-session. To start a log file interactively, simply click on the “Begin Log” icon. It is bronze-colored and is between the print and viewer (eye) icons on the toolbar. To start a log file in a do file, use the command: . log using "C:\XXXX\YYYYY\ZZZZZ.log", replace where “X”, “Y” and “Z” specify the relevant path. The “replace” option gives permission to the system to overwrite a previous log-file of the same name. If no pre-existing log-file is found, Stata will send an innocuous message stating that fact. As an alternative, the “append” option instructs the program to add the current log session to the end of an existing log-file of the same name. 4 IMPORTING DATA INTO STATA: There are several ways to import data into Stata (listed in order of ease on your part): 1) Load a pre-existing Stata file (*.dta) 2) Copy & paste from a spreadsheet, such as Excel, into Stata’s Data Editor (feasible only for a relatively small dataset.) 3) Type the numbers into Stata’s Data Editor (ditto #2.) 4) Use the “. insheet”, “. infile”, or “. infix”, command. These are relevant for Excel files, freeformatted ASCII (text) files, etc. See Appendix B for step by step instructions for using the . insheet command to import an Excel file into Stata. For additional information, type the command . help infiling in the command window to get an overview of all three methods. 5) Use a setup file and a data dictionary. This is typically the situation when using data from ICPSR. See Appendix C for more information. Unless you began with a Stata data file, once the data is loaded, save it as a Stata file, so that it will be available for future analyses using the command: . save " C:\XXXX\YYYYY\ZZZZZ.dta", replace This command was probably already included in the setup file in method #5. If methods #2 or #3 were used, rename the variables from the default names of "var1", "var2", etc., to more descriptive names. See . rename in “Creating & Modifying Variables” in the next section. You can of course rename variables created via any of the other methods, but presumably those names should already be relatively descriptive. 5 EXAMINING THE DATA The following are a few commands that will familiarize you with a data file. The next several examples use the auto.dta dataset that comes installed with Stata. Type . sysuse auto to load it. . describe gives an overview of a file. The command gives a count of the total number of observations in the file, and lists each variable by: name, type, display format, value label and label information. If the file has been sorted, the sort variable is identified. . describe Contains data from C:\Program Files\Stata10\ado\base/a/auto.dta obs: 74 1978 Automobile Data vars: 12 13 Apr 2007 17:45 size: 3,478 (99.7% of memory free) (_dta has notes) variable name make price mpg rep78 headroom trunk weight length turn displacement gear_ratio foreign Sorted by: Note: storage type str18 int int int float int int int int int float byte display format %-18s %8.0gc %8.0g %8.0g %6.1f %8.0g %8.0gc %8.0g %8.0g %8.0g %6.2f %8.0g value label variable label origin Make and Model Price Mileage (mpg) Repair Record 1978 Headroom (in.) Trunk space (cu. ft.) Weight (lbs.) Length (in.) Turn Circle (ft.) Displacement (cu. in.) Gear Ratio Car type make dataset has changed since last saved . summarize varname, detail gives mean, std. dev., variance, skewness, kurtosis, and percentiles for the “varname” variable specified. Can be abbreviated as: . su, . sum, . summ, etc. . summ mpg, detail Mileage (mpg) 1% 5% 10% 25% 50% 75% 90% 95% 99% Percentiles 12 14 14 18 Smallest 12 12 14 14 20 25 29 34 41 Largest 34 35 35 41 Obs Sum of Wgt. 74 74 Mean Std. Dev. 21.2973 5.785503 Variance Skewness Kurtosis 33.47205 .9487176 3.975005 . codebook varname gives much the same information as summarize, detail, except it includes the number of missing values, which is extremely valuable information. Observations with missing values for variables used in a regression equation will not be included. This is important to know early in a project and could have a huge impact on your analyses. To get this information for ALL the variables in the file, simply issue the codebook command without specifying the variable(s.) 6 . codebook mpg mpg Mileage (mpg) type: range: unique values: mean: std. dev: numeric (int) [12,41] 21 units: missing .: 1 0/74 21.2973 5.7855 percentiles: 10% 14 25% 18 50% 20 75% 25 90% 29 . tabulate varname creates a frequency table of occurrences. This is useful for categorical variables or continuous variables with a limited range of values. The by option is permitted. If the missing option is specified, missing values are included in the frequency counts. To ask for more than one frequency table in a single command, use the .tab1 command: . tab1, varone vartwo, etc.. . by foreign: tab mpg -> foreign = Domestic Mileage (mpg) Freq. Percent Cum. 12 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 24 25 26 28 29 30 34 2 5 2 4 2 7 8 3 3 5 3 1 2 2 1 1 1 3.85 9.62 3.85 7.69 3.85 13.46 15.38 5.77 5.77 9.62 5.77 1.92 3.85 3.85 1.92 1.92 1.92 3.85 13.46 17.31 25.00 28.85 42.31 57.69 63.46 69.23 78.85 84.62 86.54 90.38 94.23 96.15 98.08 100.00 Total 52 100.00 Mileage (mpg) Freq. Percent Cum. 14 17 18 21 23 24 25 26 28 30 31 35 41 1 2 2 2 3 1 4 1 1 1 1 2 1 4.55 9.09 9.09 9.09 13.64 4.55 18.18 4.55 4.55 4.55 4.55 9.09 4.55 4.55 13.64 22.73 31.82 45.45 50.00 68.18 72.73 77.27 81.82 86.36 95.45 100.00 Total 22 100.00 -> foreign = Foreign 7 . tabulate varone vartwo creates a crosstab table. This is useful for categorical variables. . tab rep78 foreign Repair Record 1978 Car type Domestic Foreign Total 1 2 3 4 5 2 8 27 8 2 0 0 3 9 9 2 8 30 17 11 Total 47 21 68 . tabstat varone vartwo, etc. is a more advanced alternative to the tabulate command. Tabstat produces nice tables for multiple variables, including missing variables. Desired statistics can be specified, and the by option is permitted. . tabstat price weight mpg rep78, by(foreign) stat(mean median sd variance count) missing Summary statistics: mean, p50, sd, variance, N by categories of: foreign (Car type) foreign price weight mpg rep78 Domestic 6079.627 4749 3127.482 9781143 51 3309.804 3350 700.2614 490366 51 19.90196 19 4.759222 22.6502 51 3 3 .8340577 .6956522 47 Foreign 6384.682 5759 2621.915 6874439 22 2315.909 2180 433.0035 187492 22 24.77273 24.5 6.611187 43.70779 22 4.285714 4 .7171372 .5142857 21 . 5705 5705 . . 1 3690 3690 . . 1 16 16 . . 1 4 4 . . 1 Total 6165.257 5006.5 2949.496 8699526 74 3019.459 3190 777.1936 604029.8 74 21.2973 20 5.785503 33.47205 74 3.405797 3 .9899323 .9799659 69 8 . histogram varname useful for checking that data is normally distributed and to look for outliers. By default, the histogram is scaled to density units, i.e., the sum of their areas is equal to 1. Alternatively, frequency, fraction or percent scales can be specified. The discrete option tells Stata to give each value of varname its own bar. The by option is permitted. . histogram mpg, frequency discrete by(foreign, col(1)) 0 8 Foreign 0 2 4 6 Frequency 2 4 6 8 Domestic 10 20 30 40 Mileage (mpg) Graphs by Car type . graph box varname produces a box plot, another way to visualize the data that provides more information than a histogram. Adjacent values are the 25th or 75th percentiles ± 1.5 times the Inter-Quartlile range (the distance between the 25th and 75th percentiles.) However, the adjacent values indicated on the graph, by convention, is "rolled back" to actual data points, so they always reflect real data 9 o o adjacent line <- outside values <- upper adjacent value whiskers <- 75th percentile (upper hinge) box <- median <- 25th percentile (lower hinge) whiskers adjacent line <- lower adjacent value o <- outside value 10 . tsline varname 4000 3800 3600 3400 Calories consumed 4200 4400 plots time series data. (Type . sysuse tsline2 to load the example dataset.) This command must be preceded by the . tsset command, which declares the data to be time-series. (See “Time Series” in “Creating & Modifying Variables” for more information.) Like the histogram and the box plot graphs, the time series graph can be used to look for anomalies and outliers. In the graph below, the spikes in calorie consumption at the end of the year are probably holiday eating, but the data should be checked. 01jan2002 01apr2002 01jul2002 Date 01oct2002 01jan2003 Another way to check for outliers is to see if there are values that lie more than three standard deviations away from the mean. This involves the use of the r(mean) scalar. To load the scalar with the mean for the variable that is being checked, submit the . summarize varname, detail command, then list the observations that exceed ± three standard deviations. Here are the commands and the results for the calories consumed datafile. The excessive calorie consumption did occur during the holidays and therefore are probably not clerical errors. . su calories, detail . l if calories >=r(mean) + 3*r(sd) & calories < . | calories <=r(mean)-3*r(sd) 332. 359. 362. 365. day calories ucalor~s lcalor~s 28nov2002 25dec2002 28dec2002 31dec2002 4163.4 4340.2 3896.8 3898.2 4263.4 4440.2 3996.8 3998.2 4063.4 4240.2 3796.8 3798.2 11 VERIFYING THE DATA . assert is useful for checking data, particularly in do files, where many assets can be listed back to back to check that the data really are as expected. If assertions are true, Stata quietly goes through the do file executing the commands. If an assertion is false, Stata aborts operation and gives an error message that includes the number of instances where the assertion is false. . assert gender==0 | gender== 1 2 contradictions in 365 observations assertion is false r(9); To see the contradictions, use the list command qualified by an if statement. . list if gender !=0 & gender 18. 32. !=1 day calories ucalor~s lcalor~s gender 18jan2002 01feb2002 3679 3582 3779 3682 3579 3482 . 11 .assert is also helpful after two files have been merged to see if there are non-matches. A merge value equal to 1 (_merge==1) means that the data came from the “master” file only; _merge==2 means the data came from the “using file”; a _merge==3 means both files contributed data to the observation. .assert _merge==3 More information can be found in the section on “Modifying & Combining Files.” NUMERIC MISSING VALUES As explained in the description of the . codebook command, careful consideration must be paid to missing values in a datafile. By default, Stata uses a “.” for numeric missing values. Internally, “.” is stored as a very, very large number. Most commands, like . regress, drop observations with missing values, which can cause problems if too many observations are dropped from the analysis. Just as important, other commands, like . replace, do NOT ignore them. The command .replace group=3 if group>=3 will replace any group with a missing value with a 3. To exclude missing values from the replacement, the command must be written as: . replace group=3 if group>=3 & group <. The .egen rmiss() function can be used to create a new variable that stores a count of the number of missing numeric values in each observation. An extension to the egen command rmiss2() counts the number of missing values in both numeric and string variables. It can be downloaded by typing the . findit rmiss2. The . tabmiss program creates a frequency table of the number of missing values by variable. The program works for both numeric and string variables. , It can be downloaded by typing, findit tabmiss. See: http://www.ats.ucla.edu/stat/Stata/faq/nummiss_stata.htm for more information about tabmiss and rmiss2(). 12 . correlate - CHECKING FOR CORRELATION Checking pairwise correlations gives an overview of the relationship between the numeric variables in a study. Looking at the data at this level can provide useful information for regression model specification. . correlate varone vartwo A scatterplot with regression line graph can also be informative. See: http://www.ats.ucla.edu/stat/stata/faq/scatter.htm 13 CREATING & MODIFYING VARIABLES CREATING NEW VARIABLES Variable Names: 1) Variable names are case-sensitive. Total, TOTAL and total are seen as three different variables by Stata. So, it is important to be consistent. 2) Names must begin with a letter. 3) Spaces are not allowed; use an underscore instead. 4) Names can be up to 32 characters in length. Shorter names (eight characters or less) are preferred, because longer names are often truncated in result outputs. = Versus == A single equal sign, =, is used in mathematical expressions. Use = with the . generate, . rename and . recode commands. A double equal sign, ==, is a logical operator that returns a 0 if an expression is false and a 1 if it is true. Use == with an if qualifier to test for equality. Examples include: . regress price mpg foreign if foreign == 1 . su price if region == “West” (Recall: su, sum, summ are all equally valid abbreviations for the . summarize command.) . generate To create a new variable, use the . generate (. gen) or . egen command. Spacing is not important; operators can have spaces before and/or after or none at all. Constants and variables can both be used to create new variables. For a complete list of operators, type: . help operators. Addition/Subraction . gen sum = varone + vartwo . gen sum2=varone + 10 // constants can also be used to create variables . gen net_pay = gross – deductions Division /Multiplication (Interaction) . gen total = price * quantity // total is equal to price times quantity . gen mpg=mileage/gallons // mpg is equal to mileage divided by gallons Exponentiation . gen x_sq = x^x OR . gen x_sq = x*x . gen x_cubed = x^3 OR . gen x_cubed=x*x*x 14 Lag Useful with time-series data. . gen price_lag = price[_n-1] // price_lag equals the price in the previous observation _n is a system variable that refers to the current observation. _n-1 refers to the previous observation. For a complete list of system variables, type: .help _variables in the command window. Note: If the dataset has been declared to be time-series with the . tsset command, then the . L.varname command can be used in a regression equation. This method works without creating new variables. See “Time Series” in “Creating & Modifying Variables” for more information. Log: Often used when the relationship between the dependent variable and the independent variable is not constant. . gen log_x = ln(x) . egen The egen command provides extensions to the generate command and offers very powerful capabilities for creating new variables with summary statistics. Egen works by observation (row) or by variable (column.) In the next two commands the new variables will have values based upon other variables in the same observation. . egen AvgScore=rowmean(test1 test2 test3 test4) . egen answered=rownonmiss(question1 – question25) In the next command, a summary statistic for a column of data will be added to each observation. The same value will be added, unless subsets are created using the by option. . egen subtotal = total(price) DUMMY VARIABLES There are a number of different methods that can be used to create dummy (indicator) variables which take on a value of 0 if the condition evaluates to false, and 1 if it is true. The easiest way ONLY works if there are no coding errors, so it is important to check first using either the . tab varname (tabulate) or .assert commands. The Easy Way For a variable such as “educat” with five categories: 1) no education completed 2) primary completed 3) secondary completed 4) tertiary completed 5) technical/vocational First, confirm that the variable really does have only those five categories . . tab educat, missing Second, use the following command to create the five dummy variables which by default will be named: educat_1, educat_2, educat_3, educat_4, educat_5; one for each of the “educat” categories. 15 . tab educat, gen(educat_) Finally, . rename the dummy variables to something more descriptive. It is crucial to know EXACTLY how the “educat” categories were coded. If they are coded “0” for “No education”, “1” for “Primary completed”, “2” for “Secondary completed”, “3” for “Tertiary completed”, and “4” for “Technical/vocational education completed”, then issue the following (five) commands to rename the variables: . rename educat_1 Noedu . rename educat_2 Pri . rename educat_3 Sec . rename educat_4 Ter . rename educat_5 Voc However, if they were coded “0” for “No education”, “1” for “Technical/vocational education completed”, “2” for “Primary completed”, “3” for “Secondary completed”, and “4” for “Tertiary completed”, then you would issue the following commands: . rename educat_1 Noedu . rename educat_2 Voc . rename educat_3 Pri . rename educat_4 Sec . rename educat_5 Ter Note how the subsequent analysis would be completely thrown off by a renaming mistake. If the dummies were renamed the first way when the second way really corresponded to the coding of the underlying “educat” variable, then we would effectively mistake tertiary education with technical/vocational education and vice-versa – not good if doing a wage regression!!! Second Method This way is more tedious but it is also more foolproof than the first approach. It’s foolproof because it explicitly takes into account the EXACT definition of the underlying variable from which the dummy variables were created. The dummy variables are created one at a time. Assuming that the coding of “educat” follows the first convention explained in the first method, issue the following commands to create the dummy for “Noedu”: The dummies for “Pri” through “Voc” are created using the same approach. generate Noedu = . replace Noedu = 0 if educat >=0 & educat <= 4 replace Noedu = 1 if educat==0 The first command creates the new variable, Noedu, initially with “missing” values. The second command “fills up” the missing values with zeros – note: the if qualifier explicitly takes the valid range of the “educat” variable into account. Finally, the third command replaces the zeros with ones when the if qualifier evaluates to 1 (true.) Otherwise, the zeros are left intact. Third Method The third method involves the use of the interaction expansion (. xi) command. .xi: regress wage agegrp i.educat i.race As in the first method, dummy variables are created automatically. By default, the names assigned to the dummy variables start with _I. To see their definitions, type: .describe _I* For more information, by typing . help xi in the command window. 16 DATES Any model that involves time-series data or date manipulation, such as generating an elapsed time variable, needs its date variable(s) in Stata date format. The base date used by Stata is January 1, 1960, which is assigned a value of 0. Dates prior to 1/1/1960 have negative values while dates post 1/1/1960 have positive values. Two functions are provided that will do the conversions, which to use depends upon how the dates in the file are formatted. If there are separate variables for month, day and year, then use an mdy type function: . gen birthday=mdy(month, day, year) If the date is a string variable, such as: Jan 1, 2008, then use the date function: . gen birthday=date(datevar, “MDY”) Once created, the date variable can be formatted to look more “intelligible” to humans. The format command causes a Stata date such as 17532, (17532 being the number of days since Jan 1, 1960,) to be written as 1jan2008. . format birthday %td For more information about this subject, see Stata’s .help. MODIFYING VARIABLES String Variables In Stata, non-numeric variables are called “string” variables. To specify a particular string value, enclose it in double quotes. Remember, since Stata is case-sensitive, each of the following are evaluated as unique strings. Also note the use of the double equal sign; the if qualifier is testing for equality. if gender == “male” if gender == “Male” if gender == “ male” if gender == “male ” if gender == “24450” A string variable can consist solely of numbers, but mathematical operations cannot be performed with it. Therefore it can be a good idea to format numbers for which a mathematical operation is inappropriate, such as identification numbers, as string variables. See the help file for more information on the following two approaches: . tostring or . generate as_str . destring If a variable was mistakenly imported as a string variable when it should have been numeric, the . destring command will convert it. (Remember, the . describe varname command gives information on how a variable is stored, and string variables are usually displayed as red in the Data Editor window.) Before converting the variable to a numeric format, the input error that caused it to be stored as a string must be fixed. For example, if the following set of numbers was imported as the variable batavg, the data will be stored as a string because of the comma in the third observation. .308 17 .272 ,215 .299 To fix the observation, either use the Data Editor, or. replace, the next command to be described. .replace batavg = “.215” in 3 After fixing the data entry error, the .destring command will convert the string to a numeric variable.. The safest approach is to create a new variable using the generate option, and to check the results. The original variable can be dropped and the new one renamed, once the accuracy of the conversion has been verified. . destring batavg, generate(batavg_num) . describe batavg_num . drop batavg . rename batavg_num batavg . replace This command is used to change the contents of a variable when the variable already exists. Because it is so powerful, Stata makes you type out the entire command; there are no abbreviations. It is often used with the if qualifier. The first example changes missing values that were coded as -999 to Stata’s “.” missing value. The second corrects typos in a string variable. . replace price = . if price == -999 . replace gender = “male” if gender == “mael” . recode This is a useful command to collapse a continuous variable into groups. While the . replace command can be used, it is quicker with .recode. To be safe, generate a new variable with the same values as the variable to be recoded, then work with the NEW variable, just in case a mistake is made. In the following commands categories for the continuous variable “ age” are being created: . gen AgeGrps=age . recode AgeGrps (min/18=1) (19/21=2) (22/29=3) (30/49=4) (50/66=5) (67/max=6) The recode command is also used to swap the values of a categorical variable. This is often done to match the coding of similar variables so an index can be created. For example, if two questions have a value of “1” for “Very Dissatisfied” and a value of “5” for “Very Satisfied.” but one question, quest3, has the coding reversed, recode can be used to change the values in quest3 to match those in questions 1 and 2. In the example code, the value of “3” remains unchanged, so it does not need to be specified. Again, for safety’s sake, work is being done with a copy of the variable. . gen quest3_recode=quest3 . recode quest3_recode = 1=5 2=4 4=2 5=1 18 MODIFYING AND COMBINING FILES MODIFYING A FILE . keep & . drop The keep and drop commands can be used either on variables or observations. Often when importing data, there are more variables then needed. Whether to use the . keep or the . drop command to get rid of the unnecessary variables depends upon the number of variables you want to keep. If there are more variables that you do not want, then use . keep. If however, there are only a few variables that you do not want, then use . drop. . keep varlist . drop varlist To keep or drop an observation(s) based on a set of criteria, the commands are combined with the if qualifier. . keep if mpg >= 25 & mpg < . // missing values are being dropped . drop if price < 10000 To drop specific observations, use the in qualifier. This command tells Stata to drop the first five observations. . drop in 1/5 . move & . order : reordering the list of variables The order of variables in the Variables window, and thereby in the Data Editor can be changed. In the examples below, .move relocates varone to the position occupied by vartwo and shifts the variables below down one place. The . order command places the variable(s) specified at the top of the variable list. . move varone vartwo . order newvar oldvar . sort By default, Stata sorts variables in ascending order, from smallest to biggest or from A to Z, based upon the variables specified in the varlist. .gsort sorts in descending or ascending order. The stable option insures that the observations stay in the same relative order that they held before the sort. Without this option, the order of observations that have equal sort values is randomized. /* Sorts observations in ascending order of mpg. Relative order of observations prior to the sort will be maintained for observations with equal mpg values. */ . sort mpg, stable // . gsort +mpg, stable //equivalent to the previous command; mpg is sorted in ascending order. // /* Sorts observations in descending order based on mpg. Order of observations with equivalent mpg values is randomized. */ . gsort –mpg // //* Sorts the variable make in ascending order (from A to Z) and then within each make, mpg is sorted in descending order. */ . gsort make –mpg 19 . reshape (wide long or long wide) Frequently time-series data is obtained in a “wide” format. The identifying variable is given and the time-series data values (yearly, quarterly, monthly, etc.,) are spread along the columns of a single row. In many cases, the data needs be rewritten so that the data values are separated into multiple rows. In this example, country gdp values for the years 1980-2008 are separate variables along a single observation. (Aside: country is a string variable which, by default, is red.) To reshape the data, the identifying variable (i) and the stub name (j) must be determined. In this case, country is the i variable and gdp is the “stub name” (gdp1980, gdp1981, etc.) The command becomes: . reshape long gdp, i(country) j(year) and it issues this result: (note: j = 1980 1981 1982 1983 1984 1985 1986 1987 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 > 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008) Data wide -> long Number of obs. 172 Number of variables 30 j variable (29 values) xij variables: gdp1980 gdp1981 ... gdp2008 -> -> -> 4988 3 year -> gdp The number of observations went from 172 to 4988 and there are now 3 variables when there were 30 when the data were “wide.” Issue either the .edit or . browse command to open the Data Editor. Here’s a snapshot of a few of the observations: 20 Here’s the command that would change the data back from “long” to “wide”: . reshape wide gdp, i(country) j(year) and the result: . reshape wide gdp, i(country) j(year) (note: j = 1980 1981 1982 1983 1984 1985 1986 1987 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 > 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008) Data long -> wide Number of obs. Number of variables j variable (29 values) xij variables: 4988 3 year -> -> -> 172 30 (dropped) gdp -> gdp1980 gdp1981 ... gdp2008 It is possible to have multiple identifying variables, e.g. state and city, and the j variable can be a string. If Stata detects any mistakes in the data that affect its ability to execute the reshape command, an error message instructs you to type “reshape error” to get the details. COMBINING FILES There are three ways to combine files. Additional observations from one datafile can be added to the end of another with the .append command. Additional variables contained in one file can be added to corresponding observations in another with the .merge command. The .joinby command works on groups and only keeps observations that are found in both files. All three methods use a similar approach. The datafile in memory (the one that is currently open,) is referred to as the “master” file. The file that is to be joined with the “master” is known as the “using” datafile. Both files must be Stata files. . append Append adds observations from the using file to the end of the master file. The files are stacked vertically. . append fileinmemory using AddObs . merge Merge adds additional variables to observations. If the two datafiles are in EXACTLY the same order, a matching variable contained in both files is not needed. But usually, both files have a matching variable (or variables) that is used to associate an observation from the master file with an observation in the using file. Before files can be merged, they must be SORTED. Merge creates a system variable with the name, _merge. After a merge, the . tabulate command can be used to get a frequency table of the results of the merge. The _merge variable has five possible values, but in most cases, unless the using file is being used to update the master file, the first three are the values of interest: _merge==1 _merge==2 _merge==3 observation found in master file only observation found in using file only observation built from both master & using files. Normally, this is the desired value. There are two types of merges. In a one to one match, each observation in the master file has a corresponding observation in the using file. In a one to many merge, the using file may have multiple observations per observation in the master file. Both types of merges work in the same manner. Here is some example code that could be saved in a do file to accomplish a one to many merge: 21 version 10.0 * Load, sort and save master file use patient.dta, clear sort id save patient.dta // * Load, sort and save “using” file use visits, clear sort id, stable // stable option maintains the relative order of observations . save visits // * Reload master file and merge with using file by id use patient.dta, clear merge id using visits // joins observations in the patient file with obs in the visit file by id. // tab _merge // Check to see how the merge worked. (tab is an abbreviation for . tabulate.) drop _merge // If the merge worked as planned, the _merge variable should be dropped. save AllInfo, replace TIME SERIES AND PANEL DATA A data file that contains observations on a single entity over multiple time periods is known as time series data. If, as in the gdp example above, there is a group for whom there is data over a number of time periods, then it is known as panel data. To use Stata’s time-series functions and capabilities, the dataset must be declared to be time-series data. There are a number of items that need to be accomplish before that can be done. First, the dataset must contain a date variable and it must be in Stata date format. Second, the data must be sorted by the date variable. If it is panel data, the data must be sorted by date within the panel variable(s). Finally, Stata must be told that the file contains time-series or panel data with the . tsset command. Stata can be used to create a time variable for a dataset that does not have one, but the data must be in the correct time sequence and there can NOT be any gaps in the time series. To create a year variable that begins in 1975, issue the commands: . generate year = 1975 + _n-1 To generate a monthly variable beginning in July of 1975 for a panel dataset, the commands would be: . sort country . by country: generate time=m(1975m7) +_n-1 . format time %tm To declare a file with yearly data to be a time-series dataset and then to plot the data, issue these commands: . sort year // Data must be sorted before the . tsset command can be used. . tsset year, yearly // Declares data to be time series. . tsline gdp // Plots the time series data. See “Examining the Data.” Stata’s response would be: . tsset year time variable: delta: year, 1980 to 2008 1 year To . tsset a panel data file, that contains gdp values for multiple countries, the commands would be: 22 . format year %ty . sort country year . tsset country year, yearly . xtline gdp // Plots the a time series graph for each country in the dataset. Note, the panel variable comes before the time variable and unfortunately, it must be numeric ! So the above commands would not work if the country variable is a string variable. First, a numeric id number for each country must be generated. This code will generate an id number for each country and then declare that the file contains panel data. . sort country year . egen cntryid=group(country) // This assigns the values of 1, 2, 3, etc to the various countries. . tsset cntryid year, yearly Here are the results: . tsset cntryid year, yearly panel variable: cntryid (strongly balanced) time variable: year, 1980 to 2008 delta: 1 year Frequently, in time series analysis, it is desirable to “lag,” “lead,” or compute the difference between the value of a variable and adjacent observations. Since the data has been declared to be a time series, the time series operators, (L., F., and D,) can be used. There are several advantages to this approach, the most important being that it is less error prone than other techniques. Another positive is that this method does not created new variables. Time Series Operators L. is equivalent to x[_n-1], i.e., the value of x in the previous observation. L2. is the value of x two time periods in the past. (The lag can be any desired amount.) F. is equivalent to x[_n+1], i.e., the value of x in the next observation. D. is equivalent to the difference between the current value and the previous value. All these commands follow the same syntax, so just a lag example will be demonstrated. In a regression equation, specify the variable to lag or lead and the number of time periods desired. . regress wage L.wage L.2wage The command to clear time series settings is . tsset, clear. 23 REGRESSION ANALYSIS OLS (Studenmund, pp. 35 – 40) . regress Y X1 X2 X3 To predict residuals and save the results as "Residuals,” use the command: . predict Residuals, resid To plot residuals together with suspected proportionality factor (to detect heteroskedasticity): . twoway scatter Residuals X3 Restricting Stata commands to observations with certain conditions satisfied You may want to calculate descriptive statistics and/or estimate a regression, say, for the full sample, as well as for females and males separately (micro data) or full sample, OECD-countries, Non-OECD countries, SubSaharan African Countries (macro data). One thing to notice here, is that when it comes to conditions like these, Stata needs two equality signs, rather than one – for the previous two examples, say: .summarize Y X1 X2 X3 . summarize Y X1 X2 X3 if X3==1 . summarize Y X1 X2 X3 if X3==0 . regress Y X1 X2 X3 . regress Y X1 X2 X3 if X3==1 . regress Y X1 X2 X3 if X3==0 // . summarize Y X1 X2 X3 . summarize Y X1 X2 X3 if oecd==1 . summarize Y X1 X2 X3 if oecd==0 . summarize Y X1 X2 X3 if ssa==1 . regress Y X1 X2 X3 . regress Y X1 X2 X3 if oecd==1 . regress Y X1 X2 X3 if oecd==0 . regress Y X1 X2 X3 if ssa==1 Note that in the regression-case, it does not matter whether the variable, you restrict upon, is included as an explanatory variable or not – Stata will detect that it is collinear (since there will be no variation in it) and automatically exclude it from the explanatory variables. Ensuring Consistency Among the Number of Observations in the various estimation samples In descriptive analyses, the number of observations often differs across the variables. Similarly, the number of observations will likely differ for regressions using various specifications of explanatory variables. This is due to some observations having missing values for some variables but not for others, thus creating “holes” in the number of observations. You want: 1) The number of observations for each variable within the descriptive analysis to match up. 2) The number of observations used in the different regression specifications to match up. 24 3) The number of observations between (1) and (2) to match up. To ensure this, do the following: 1) Load your Stata dataset. 2) Run the model specification that gives rise to the biggest drop in sample size: . regress Y X1 X2 X3 X4 X5 X6 X7 X8 X9 X10 3) Use . keep to retain only the observations that have non-missing values for all variables, dependent and explanatory, from the above regression: . keep if e(sample) 4) Stata will then drop all the observations that have one or more missing (dependent and/or explanatory) variables – so that all subsequent analyses will be performed on one, consistent dataset. Ramsey’s Regression Specification Error Test (RESET) (Studenmund, pp. 198 - 201) Run the regression of interest, then: . regress Y X1 X2 X3 . estat ovtest Akaike’s Information Criterion and the Schwartz (Bayesian Information) Criterion (Studenmund, p. 201) Run the regression of interest, then: . regress Y X1 X2 X3 . estat ic Detection of Multicollinearity: Variance Inflation Factors (Studenmund, p. 259) Run the regression of interest, then: . regress Y X1 X2 X3 . estat vif SERIAL CORRELATION In order to use any time-series analysis related commands in Stata, including running a DW test, you must first define the dataset to be a time-series dataset (if this has not already been done). Tell Stata which variable defines the time dimension (here, “qtrs.”) For more information about the .tsset command, see “Time Series” in the previous section (Modifying & Combining Files.) Durbin-Watson D Test for First-Order Autocorrelation (Studenmund, p. 325) If it has not been done already, tell Stata it is dealing with time series data, run the regression of interest then check for serial correlation: . tsset qtrs . regress Y X1 X2 X3 . estat dwatson 25 Dealing With Autocorrelation GLS Using Cochrane-Orcutt Method (Studenmund, p. 332) Letting Y be the dependent variable and X1, X2, and X3 explanatory variables, issue the command: . prais Y X1 X2 X3, corc Newey-West standard errors (Studenmund, p. 334) Again letting Y be the dependent variable and X1, X2, and X3 explanatory variables, issue the command: . newey Y X1 X2 X3, lag(#) where “lag(#)” specifies the order of the autocorrelation – again, we will typically think only first-order autocorrelation is relevant, and therefore specify “lag(1)” but if you think second-order autocorrelation might be relevant, you could go on to specify “lag(2).” HETEROSKEDASTICITY White test (Studenmund, p. 360) Run the regression of interest, then: . regress Y X1 X2 X3 . estat imtest, preserve white Weighted-Least Squares (WLS) (Studenmund, p. 363) At the time of writing, Stata does not contain a direct WLS procedure but you can download the user-written “wls0” command and then use that from within Stata (see http://www.ats.ucla.edu/stat/stata/ado/analysis/wls0.htm for more details and an example.) Heteroskedasticity-corrected (HC) standard errors (Studenmund, p. 365) Run the regression of interest, specifying the “robust” option: . regress Y X1 X2 X3, robust 26 HYPOTHESIS TESTING t-tests The results (t-statistics and the p-value of the t-statistics) here are automatically provided – for the two-sided alternative if you want to test one-sided, you’ll need to divide the p-value by two – AND check that the sign is in the expected direction!! f-tests Again, the t-test is a partial test, i.e., it tests for the statistical significance of each individual regressor/explanatory variable in turn If we want to perform tests that involve a group of variables, we need something else – one possibility is the F-test. There are two “flavors” to consider: Tests for joint statistical significance of explanatory variables 1) Run the regression of interest, say: . regress Y X1 X2 X3 X4 X5 2) Perform (an) F-test(s) of the group(s) of explanatory variables, you are interested in, say: . test X1 X2 and/or: . test X1 X2 X3 Stata will give you the F-Statistic and its associated p-value for a test of the null hypothesis of lack of joint statistical significance and the alternative hypothesis of joint statistical significance for the group of explanatory variables as a whole (recall the decision rule for statistical tests when using the p-value!) Testing for equality of coefficients Alternatively, we may be interested in testing whether the coefficients for a group of explanatory variables are equal. For example, whether the coefficients for a set of dummy variables for different ethnicities in a wage regression are the same. 1) Run the regression of interest, say: . regress Y X1 X2 X3 X4 X5 2) Perform (an) F-test(s) of the group(s) of explanatory variables, you are interested in testing for identical coefficients – say: . test X1 = X2 and/or: . test X1 = X2 = X3 Here, the null hypothesis is that all the coefficients are equal to each other and the alternative hypothesis is that at least one of the coefficients is different from the other coefficient(s). 27 MAKING “NICE” TABLES OF REGRESSION RESULTS The default in Stata is to report results in a “wide” format, i.e., the estimated parameters in the first column, the estimated standard errors in the second column, etc. There are two different approaches to creating “nice” tables – similar to how results are reported in journal articles, i.e., with the standard errors below the parameter estimates, along with fit measures (R2, adjusted R2, Akaike Criterion, etc.,) and the number of observations, etc., at the bottom. The first gives you the brackets around the standard errors, as in most journal articles. The second is more comprehensive, allowing you to include t-statistics, p-values, several different fit measures (rather than merely R2), etc., but you have to make the brackets around the standard errors yourself. The two methods work as follows: . outreg2 1) This is a user-written command, so first you need to install it from the Stata collection at Boston College: . ssc install outreg2, all replace 2) Run the first regression that you want to be part of the table – and then save the results in a text-file, specifying the path where you want to save it, replacing any existing file with the same name: . regress Y X1 X2 X3 . outreg2 using “C:\capstone\result_tbl_1.out”, nolabel bdec(3) coefastr se bracket 3aster replace 3) Run the additional regressions that you want to be part of the table, appending them to the previous results: . regress Y X1 X2 X3 if X3==1 . outreg2 using “C:\ capstone\result_tbl_1.out”, nolabel bdec(3) coefastr se bracket 3aster append . regress Y X1 X2 X3 if X3==0 . outreg2 using “C:\ capstone\result_tbl_1.out”, nolabel bdec(3) coefastr se bracket 3aster append 4) Import the text-file into Excel, to create the table, then copy and paste into Word. THE “ESTIMATES STORE” AND “ESTIMATES TABLE” COMMANDS: 1) Run the regression(s), that you want to be part of the table, saving the results after each regression: . regress Y X1 X2 X3 . estimates store model1 . regress Y X1 X2 X3 if X3==1 . estimates store model2 . regress Y X1 X2 X3 if X3==0 . estimates store model3 2) Create the table, by calling the model results, that you saved previously, and add the statistics, etc, you want to include (here, we ask for coefficients, standard errors, t-statistics, p-values + R2, adjusted-R2, the Akaike Information Criterion, the Bayesian Information Criterion, and the number of observations) : . estimates table model1 model2 model3, stats(r2 r2_a aic bic N) b(%7.3g) se(%6.3g) t(%6.3g) p(%4.3f) 28 NOTE: if there is some parts of the previous table, you don’t want to include, you just modify the previous Stata command accordingly. Say, you are not really interested in the t-statistics or p-values but only want to include the coefficients and their standard errors (+ the fit measures and N from before): . estimates table model1 model2 model3, stats(r2 r2_a aic bic N) b(%7.3g) se(%6.3g) Note that if you want “stars” to indicate the level of statistical significance, you CANNOT combine this with the “se”, “t”, and/or “p” options from above. An example on getting “stars” in the fashion known from economic journals, etc, similar to the previous, is: . estimates table model1 model2 model3, stats(r2 r2_a aic bic N) b(%7.3g) star(0.1 0.05 0.01) 3) Highlight the table (i.e. from top edge of table down to and including the bottom line of the table – do NOT highlight the legend, that will mess up the formatting in Excel subsequently!!) in the results window with the cursor, right-click on it and chose “Copy Table” (NOT “Copy Text”) and then copy and paste into Excel, to create the table, then copy and paste into Word. 29 MORE ADVANCED REGRESSION MODELS . logit & . probit models Relevant whenever the dependent variable is a binary (i.e. “dummy” or (0,1) variable). Consult an econometrics textbook for details!! In Stata, type, say (for the probit and logit, respectively): . probit Y X1 X2 X3 . logit Y X1 X2 X3 Issue: since the logit and probit models are non-linear in the estimated parameters (unlike the OLS model), the estimated coefficients are not directly interpretable as marginal effects (again, unlike in the OLS model). The reason for this is that due to the non-linearity, the marginal effects of a given explanatory variable will depend on the value of ALL other explanatory variables, as well. We therefore need to evaluate the marginal effects of a given explanatory variable at some value of the other explanatory variables. Typically we’ll set all the other explanatory variables at their mean value. To run logit and/or probit models in Stata, where the results yield marginal effects type, say: Probit with marginal effects reported . dprobit Y X1 X2 X3 Or: 1) Run the probit of interest: . probit Y X1 X2 X3 2) Calculate the marginal effects, evaluated at the means of all other explanatory variables: . mfx Logit with marginal effects reported 1) Run the logit of interest: . logit Y X1 X2 X3 2) Calculate the marginal effects, evaluated at the means of all other explanatory variables: . mfx Multinomial logit Relevant whenever the dependent variable is a qualitative variable with more than two outcomes that cannot be ordered/ranked (if it could be ordered/ranked, we would use, for example, an ordered probit – and if it had only two outcomes, we would use instead the (simple) probit and/or logit model, discussed previously.) Examples include transportation choice (car, bus, train, bike, etc), health provider (doctor, healer, etc). NOTE: Consult an econometrics textbook for details!! 30 In a do file, type: mlogit Y X1 X2 X3 X4 X5, basecategory(#) mfx, predict(outcome(#)) mfx, predict(outcome(#)) mfx, predict(outcome(#)) mfx, predict(outcome(#)) where Y is the dependent variable and the Xs are the explanatory variables. The "#" after “basecategory” sets the category you want to be the reference category (all results are relative to this category). Which one you choose matters mostly for the interpretation, although it is better to have a reference group with a relatively high number of observations (yields relative more precise estimates for the estimated parameters (i.e. the coefficients), since the coefficients, again, are relative to the base category). Again we have a problem with the estimated coefficients not being interpretable as marginal effects (since the multinomial logit model is non-linear in the estimated parameters – as were also the (simple) logit and probit models from before) – and again the “mfx” command calculates the marginal effects (again, here these are to be interpreted as the marginal probability, ceteris paribus, for the outcome in question – since the dependent variable is qualitative). Again, we will typically set all the other explanatory variables at their mean value (which is also the default for the “mfx” command). Aside: because marginal effects add up to one, unlike what was the case for the coefficients, we can calculate marginal effects for ALL outcomes (the "#" after “outcome” refers to the particular outcome of the dependent variable for which you want to calculate the marginal effects. If you want to know more about the command, type . help mlogit in Stata. 31 APPENDIX A DO FILE EXAMPLE * Note: actual commands are in bold face type and all 3 types of comment markers are used as examples. /* Three good commands to include no matter what the rest of the program is doing. */ version 10.0 /* Set the version of Stata (you can see the current version number by typing “version” in Stata’s command window.) (NOTE: Sometimes user-written commands may work only under an older version of Stata, say, version 9 – in that case, one would type “version 9.0” below, instead) */ capture log close // Close any open log-files. clear // Clear memory allocated to Stata in order to start with a clean slate. /* The next two commands may be necessary when working with large datasets. The amount of memory that can be assigned depends upon the memory of the machine in use and the number of other programs that are running. */ set memory 300000k // increase memory assigned to Stata. set matsize 200 // increase the number of parameters allocated for dataset /* Open a log file to document the session. Specify the relevant path rather than the “X”s, “Y”s, and “Z”s. The replace option permits overwriting of a file with the same name. */ log using "C:\XXXX\YYYYY\ZZZZZ.log", replace /* Load the Stata file by specifying the complete path rather than the “X”s, “Y”s, and “Z”s. There are many methods for creating a Stata datafile: copying and pasting, data entry in the Data Editor, and the . insheet command are a few examples. */ use " C:\XXXX\YYYYY\ZZZZZ.dta", clear /* Get to know the data, run a regression, save residuals and plot residuals to look for heteroskedasticity. */ summarize // Get basic descriptive statistics for all variables. Specify specific variables, if desired. histogram X1 // Check variable X1 for outliers. graph box X2 // Create a box plot for variable X2 to check for outliers. twoway scatter X1 X2 // Create scatter plot with X1 on Y axis and X2 on X axis correlate X1 X2 // Estimate the partial correlation between X1 and X2 regress Y X1 X2 // Estimate an OLS regression of Y on X1 and X2 predict Residuals, resid // Predict residuals and save as a new variable called, "Residuals" twoway scatter Residuals X3 /* Plot residuals with suspected proportionality factor, X3, (to detect heteroskedasticity) */ Wrap up work: save file with new name, close log file and exit do file. */ save " C:\XXXX\YYYYY\newfile.dta" // Save file with Residuals variable under new name, if desired. capture log close // Close log file. exit // Return control to the operating system, not necessary, but good practice. 32 APPENDIX B IMPORTING AN EXCEL FILE INTO STATA 1. Excel file a. Delete titles and footers b. Assign short variable names (8 characters), NO SPACES i. Names can be as long as 32 characters, but long names will likely be truncated when displayed and that can cause identification problems. ii. Use an underscore rather than a space, e. g., net_inc c. Save as *.csv 2. Stata a. . insheet using filename, comma names case i. comma option is not necessary, but it speeds things up. ii. names option tells Stata that variable names are included in the file, which on occasion the program does not recognize. iii. case option instructs Stata to keep variable names in the case specified in the spreadsheet, otherwise variable names become all lower case. b. open Data Editor to look at file; by default, string variables are red and numeric variables are black c. . count, . codebook, .describe, .summarize commands may be useful 3. Destring command to change a variable from string to numeric a. sometimes coding errors can cause numeric variables to be imported as string variables. b. examples include double periods “..” or commas “,,” in a column. c. . destring varname, replace ignore(".." ",,") fixes this situation. d. The ignore option changes the “..” and to “.” and makes the variable a numeric. 4. Changing missing values to Stata missing value codes. a. many data files use “-9” to indicate a missing value; this is NOT a missing value in Stata b. Stata uses “.” (and .a, .b, ... .z for more extensive tracking of missing values) c. “.” is the value to use d. . recode varlist ( -9 = .) 33 APPENDIX C DOWNLOADING DATA FROM ICPSR Washington & Lee is a member institution of ICPSR, so we can download files from that site. You will be asked to log in, or if you are a first time user, to register, when you try to download data. The download process has five steps: Step 1: If there is a Stata DTA option, select it. If there isn’t a *.dta file, select the ASCII Data File + Stata Setup Files option if one exists. 34 If neither a *.dta nor a Stata setup file is available, ask Carol Karsch, the Data & Statistical Support Specialist at Leyburn Library. She can work with both SAS and SPSS. Step 2: From the list of available datasets, select the item(s) of interest Step 3: Add the data to the cart Step 4: Review the cart (if desired.) Step 5: Download the cart You’ll be sent a “zipped” folder that needs to be decompressed before you can work with it. Usually, there is a “Codebook” , a “descriptioncitation” which gives a brief synopsis of the study’s methodology, a manifest, which gives technical details, a related_literature document, in addition to the data and setup files. The codebook should be carefully read before work with the data begins. A codebook describes the study. It gives details about the data that are extremely useful. If the variables in the dataset are not labeled, the codebook is indispensable. The codebook describes the variables, their locations in the file, what the values mean and potential information about the variables that is necessary to using them correctly. It helps the researcher verify that the data will be useful for the purpose intended. It may not! The data might not have the level of detail required. If the analysis is a time series, the questions important to the research may not be asked in the years under consideration. Groups important to the analysis maybe dropped because of privacy issues. A careful reading of the codebook(s) can prevent a lot of wasted effort and much frustration. USING A STATA SETUP FILE TO IMPORT ASCII DATA INTO STATA This ICPSR webpage gives thorough instructions for using Stata setup files: https://www.icpsr.umich.edu/cocoon/ICPSR/FAQ/0127.xml Basically, the *.do file must be edited with a text editor, e.g., Notepad. The paths and filenames of the ASCII data file (*.txt), the Stata dictionary file (*.dct) and the output file, i.e., the Stata dataset have to be specified with COMPLETE filenames, including extensions. If there is an embedded space in the filename, it must be enclosed in double quotes. Here is an example for ICPSR Study # 07644. 35 This is the section that needs to be edited. The program will use the filenames supplied in the sections below. Here is the edited version: 36 The code to replace missing values is usually commented out, so it isn’t executed. To change missing values to a “.” which Stata recognizes as a missing value, delete the comment markers ( /* and */) at the beginning and end of the section. Deleting these will change all missing values to “.” Finally, it is good practice to type the . exit command at the bottom of the file. Save and close your edited version of the *.do file. Opening the file will launch Stata, and if all goes well, the Stata dataset will be created! 37