SOC610 Topics in Social Science Data Analysis

advertisement

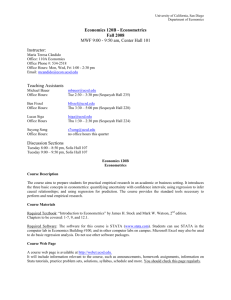

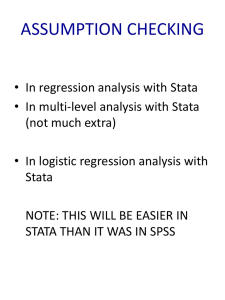

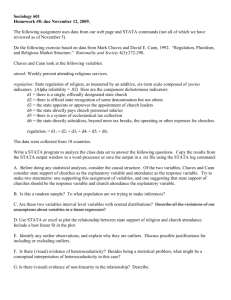

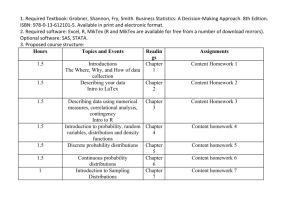

SOC610 Topics in Social Science Data Analysis A two-quarter, variable-credit seminar & workshop: Winter & Spring 2014 Seminar meets every other week during Winter and Spring terms Prof. Caleb Southworth Dept. of Sociology, 740PLC caleb@uoregon.edu This course is a seminar in data analysis. The goal of the course is to expand and refine your toolbox of data management and data analysis techniques. The course differs from a traditional statistics course with a textbook in that the seminar will cover a wide variety of data cleaning tasks and present many alternative ways to look at your data. The intended audience is graduate students who are working on a thesis, research project, or dissertation. The seminar is relevant to many areas of study. Students in journalism may be interested in methods of extracting web-based data and analyzing time trends; in Political Science, analyzing the life history of regimes; in Economics and Business, models of organizational success or failure; in Sociology, questions of spatial or network structure; in Psychology, analysis of social context and individual decisions. The tools in the course are quite general and apply to all sorts of scientific problems. The emphasis is on clear questions, visual presentation and grant writing, all of which should have interdisciplinary appeal. In the seminar, we will use a wide variety of software. The main package for the course is Stata, but we will also use R, SAS, nVivo, StatsNet, Mathematica, LaTex, GeoDa and a variety of other free and open-source software. You are encouraged to bring your own favorite software to class and put it to use. Every effort will be made to have the substance of the course be platform and software independent. Course Structure The course is spread out over two quarters and there are five workshops per quarter. Each workshop demonstrates a particular technique, offers a set of exercises with an existing dataset, and then turns to students’ own particular interests, problems and data. You are welcome to attend any portion of the seminar. Hour 1: Lecture & Demonstration of a specific technique Hour 2: Hands-on laboratory. Data provided. Students tackle a problem within the particular topic area. Hour 3: Consultation. Office hours dedicated to data management and analysis. Analyze your data and problems in a group setting. Enrollment and Grading Options Everyone is welcome at any or all of the workshops and/or the consulting office hours. The department asks that students enroll under one of the following options: Option 1a: P/NP, attend and participate and receive 2 credits per quarter (This is the default enrollment option; students may enroll in one or both quarters.) Option 1b: P/NP, attend and participate in two workshops and receive 1 credit per quarter. Option 2: Graded, attend and participate in all workshops over two quarters and receive 4 graded credits Option 3: Research Methods credit. Students receive credit for a graduate methods course when they attend over two terms and turn in a research project using one or more of the techniques presented in the course. Students receive 5 graded credits for this choice. Required Software & Materials The course requires that you have a laptop and Stata 13 installed. A one-year graduate student license costs $98. There are other purchase options. (http://www.stata.com/order/new/edu/gradplans/#3) Recommended software includes: A unix operating system of any flavor StaTransfer (2-year license = $69) R-Project for Statistical Computing (free, http://www.r-project.org/) Topic Areas These are proposed topic areas. Many of them we will definitely cover, such as making tables for publication. Others will be determined by the interest of the participants. Within topic areas, there is substantial room for emphasis on specific problems from students’ dissertations or research projects. 1: Constructing Regression or ANOVA Tables for Publication Most statistics courses focus on the creation and interpretation of point estimates and overlook the mechanical and conceptual issues that go with presentation of results in tables. At the end of this workshop you will know how to run an analysis and automatically print a table of coefficients in the format of a journal. This is done without typing anything on the table. You can change one parameter and receive a revised, publication-ready table immediately. We will discuss best practices for tables and data summary. Ian Watson. “Publication quality tables in Stata: a tutorial for the tabout program.” The Stata Journal. Fear, S. 2003. “Publication Quality Tables in LATEX.” Documentation for the booktabs package, www.ctan.org/texarchive/macros/latex/contrib/booktabs/booktabs.pdf. Tufte, ER. 2001. Visual Display of Quantitative Information. Graphics Press. 2: Analysis of Time-Series Data Here the emphasis is on establishing a time trend and being able to identify a case or cases in a set that exhibit a specific temporal pattern. Does crime respond to stateor country-level social policy? Do welfare program change public health outcomes? Does urban planning affect human behavior in cities? Hochheiser, H., Shneiderman, B. Visual Specification of Queries for Finding Patterns in Time-Series Data Proceedings Discovery Science 2001, University of Maryland, Computer Science Dept. Technical Report #CS-TR-4326. UMIACSTR-2001-25. Jeffrey Wooldridge. 2012. Introductory Econometrics: A modern approach. Part II: Regression with Time-Series Data. 5th Edition (any addition is acceptable) 3: Analysis of Panel Data Panel data are common in the social sciences. Repeated observations on people, cities, states, countries or organizations over time. It is equally common for students to have a panel data problem and to have difficulty putting the data in the correct format, especially when pooling from multiple sources. The reward for that work, however, is statistical control of original states or starting conditions and the additional leverage of observing the same unit over time. Robert Yaffee. 2003. “A Primer for Panel Data Analysis.” 4: Event History Analysis Event history, survival analysis or life history data all refer to the same set of methods. These methods deal with the time until an event occurs and have been used to analyze diseases and treatments, domestic violence, regime change, and organizational mortality. A key component of survival analysis is the necessity of dealing with censored data, where observations join the analysis at different points and drop out in a possibly non-random pattern. Paul Allison. 2003. Survival Analysis Using SAS. A Practical Guide. 5: Visualizing Data, Graphical Methods Exploratory data analysis (EDA) is a family of graphical techniques to visually describe data. EDA includes plots, line drawing, mapped data, and many graphical ways of summarizing the relationships present. It is particularly useful in developing concepts and hypotheses. EDA has answers for some common problems in the social sciences: What would replications of a social science experiment look like? What can be done if my data are not a random sample? How well do my data meet the assumptions of specific techniques, such as regression? How can interactions in continuous data be graphed? John W. Tukey. 1977. Exploratory Data Analysis. Addison-Wesley Publishing Co. William S. Cleveland. 1985. The Elements of Graphing Data. Wadsworth. Edward Tufte. 2006. Beautiful Evidence. 6: Qualitative Comparative Analysis Social science research often involves comparison of composite cases, which are bundles of discrete events. This approach draws on Boolean algebra and Bayesian inference methods to analyze patterns in rare events where increasing the sample size is not practicable. Under what conditions do revolutions occur? When will a labor union go on strike? When does a protest turn violent? Models of these events as continuous processes make little sense and the number of viable cases is always small. Here the emphasis is on describing a pattern of unique events and asking to what extent a particular hypothesis could have generated the observed pattern. Charles C. Ragin. 1987. The Comparative Methods. University of California. 7: Categorical Dependent Variables Categorical dependent variables are a common occurrence in the social sciences. Which candidate did you vote for? Did you complete high school? Are you unemployed? Do you participate in a protest? Black and white decisions about social action describe many choices. However, like other bounded dependent variables, models of such outcomes require a particular type of non-linear function. Likewise, these models require particular attention to marginal change, something best described graphically. J. Scott Long and Jeremy Freeese. 2006. Regression Models for Categorical Dependent Variables. Stata Press. 8: Missing Data Problems Missing data occur in all scientific research. Deleting them is unsatisfactory as such data are often not missing at random. Reweighting to make the remaining distribution resemble the population likewise ignores selection in the process generating the missing data. Instead, social scientists need to understand why the data are missing and arrive at a solution that permits the analysis of the remaining cases without bias. Paul D. Allison. 2001. Missing Data. Sage. 9: Grant Writing for Social Scientists Grant writing is an integral part of academic life, but students are rarely schooled in it. The goal of this unit is to get you to see the grant proposal from the reviewers' perspective. It is based on my decade of service at the National Science Foundation and review work for many other granting agencies. Writing a clear, concise grant proposal will help you write convincing papers and theses. Pzreworski, Adam and Salomon, Frank. 2000. "The Art of Proposal Writing." Social Science Research Counsel. 10: Analysis of Interactions, Categorical & Continuous Interactions are present in many types of models and often ignored. This unit will walk you through the simple, two-variable binomial interaction. From there we will learn to graph and understand complicated interactions of continuous variables, many of which do not have a single-modal distribution. How does the effect of income on obesity vary across social class? How do class, race and religion vary across the geography of a city to explain voter choice? Leona Aiken and Stephen G. West. 1991. Multiple Regression: Testing and Interpreting Interactions. Sage.

![Discipline: [eine der fünf Kernfächer] - INNO-tec](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/007121087_2-cd32a6afc92211d62c8d2e98f2ad3135-300x300.png)