wislizenus - Manuel Lisa Party

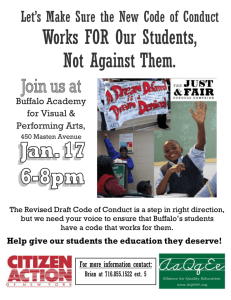

advertisement