Chapter 2

advertisement

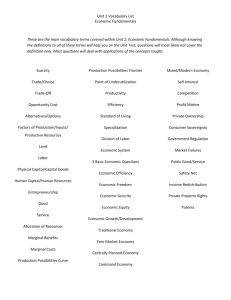

2 THE ECONOMİC PROBLEM Outline Good, Better, Best! A. For many people, life is good and getting better, but we all face costs and must choose what we think is best for us. B. This chapter sharpens the concepts of scarcity and opportunity cost, introduces the idea of economic efficiency, and explains how we can expand production by accumulating capital and specializing and trading with each other. I. Production Possibilities and Opportunity Cost A. Production Possibilities Frontier 1. The production possibilities frontier (PPF) is the boundary between those combinations of goods and services that can be produced and those that cannot (ceteris paribus). 2. The PPF in Figure 2.1 (page 32) shows the combinations of “guns” and “butter” (standing for any pair of goods and services) that can be produced ceteris paribus. 3. Points inside and on the frontier are attainable and points outside the frontier are unattainable. C. Production Efficiency 1. We achieve production efficiency if we more of one good cannot be produced without producing less of another good. 2. Points on the frontier utilize all the available resources and are efficient. 3. Any point inside the frontier, such as point Z, is inefficient because at such a point it is possible to produce more of one good without producing less of the other good. At Z, resources are either unemployed or misallocated. E. Tradeoff Along the PPF 1. When we operate efficiently along the PPF, we face a tradeoff. F. Opportunity Cost 1. The PPF makes the concept of opportunity cost precise. a) As we move along the PPF and produce more butter, (for example a move from C to D in Figure 2.1) the opportunity cost of butter is the decrease in gun production from 12 units to 9 units, a decrease of 3 units, divided by the increase in butter production from 2 tons to 3 tons, an increase of 1 ton. So the opportunity cost is 3 units/1 ton or 3 units of guns per ton of butter. b) As we move along the PPF in the opposite direction and produce more guns, (for example a move from D to C in Figure 2.1) the the decrease in butter production from 3 tons to 2 tons, a decrease of 1 ton, divided by the increase in guns production from 9 units to 12 units, an increase of 3 units. So the opportunity cost is 1 ton /3 units or 1/3 of a ton of butter per unit of guns. 2. Note that the opportunity cost of guns is the inverse of the opportunity cost of butter. 3. Because resources are not all equally productive in all activities, the PPF bows outward—is concave. The outward bow of the PPF means that as the quantity produced of each good increases, so does its opportunity cost. Increasing opportunity cost is a widespread phenomenon. II. Using Resources Efficiently A. All the points along the PPF are efficient. To determine which of the alternative efficient quantities to produce, we compare costs and benefits. B. The PPF and Marginal Cost 1. The PPF determines opportunity cost. 2. The marginal cost of each good or service is the opportunity cost of producing one more unit of it. Figure 2.2 (page 35) illustrates the marginal cost of butter. a) As we move along the PPF in part (a), the opportunity cost and the marginal cost of butter increases. b) In part (b), upward-sloping MC curve shows the rising marginal cost of each additional ton of butter produced. C. Preferences and Marginal Benefit 1. Preferences are a description of a person’s likes and dislikes. We can describe preferences by using the concepts of marginal benefit and the marginal benefit curve. 2. The marginal benefit of a good is the benefit received by an individual from consuming one more unit of that good. a) We measure marginal benefit by what a person is willing to pay for an additional unit of a good. b) The willingness to pay for any good decreases as the quantity consumed of that good increases—the principle of decreasing marginal benefit. 3. The marginal benefit curve shows the relationship between the marginal benefit of a good and the quantity of that good consumed. a) Figure 2.3 (page 36) shows a marginal benefit curve. b) The curve slopes downward to reflect the principle of decreasing marginal benefit. D. Efficient Use of Resources 1. Allocative efficiency occurs when we cannot produce more of one good or service without producing less of another good or service that we value more highly— when we produce at the point on the PPF that we prefer above all other points. 2. Figure 2.4 (page 37) illustrates allocative efficiency. a) Because marginal cost increases and marginal benefit decreases, at a low output of butter, its marginal benefit exceeds its marginal cost—people are willing to pay more than they have to pay, so they are better off producing more butter. b) At a high output of butter, its marginal cost exceeds its marginal benefit—people must pay more than they are willing to pay, so they are better off producing less butter. c) Allocative efficiency occurs where marginal benefit equals marginal cost. III. Economic Growth A. The expansion of production possibilities—and increase in the standard of living—is called economic growth. To make our economy grow, we face a standard of living tradeoff B. The Cost of Economic Growth 1. Two key factors influence economic growth: a) technological change, which is the development of new goods and better ways of producing goods and services; and b) capital accumulation, which is the growth of capital resources, including human capital. 2. To use resources in research and development and to produce new capital, we must decrease our production of consumption goods and services. Figure 2.5 (page 38) illustrates this tradeoff, using the example of butter and butter making machines. By using some resources to produce butter making machines, the PPF shifts outward in the future. D. Economic Growth in the United States and Hong Kong 1. Some nations have chosen faster capital accumulation at the expense of current consumption and have experienced faster economic growth. 2. Figure 2.6 (page 39) illustrates and compares Hong Kong and the United States. IV. Gains from Trade A. Comparative Advantage 1. A person has a comparative advantage in an activity if that person can perform the activity at a lower opportunity cost than anyone else. 2. Figure 2.7 (page 40) shows Tom’s PPF for CD discs and cases. Along his PPF, Tom’s opportunity cost of a disc is 1/3 of a case and his opportunity cost of a case is 3 discs. 3. Figure 2.8 (page 41) shows Nancy’s PPF for CD discs and cases. Along her PPF, Nancy’s opportunity cost of a disc is 3 cases and her opportunity cost of a case is 1/3 of a disc. 4. Because Tom’s opportunity cost of producing discs is less than Nancy’s, he has a comparative advantage in disc production. And because Nancy’s opportunity cost of cases is less than Tom’s, she has a comparative advantage at producing cases. 5. If Tom and Nancy produce discs and cases independently, they can produce 1000 complete CD units each (2000 total) at point A in Figure 2.8. B. Achieving the Gains from Trade 1. Figure 2.9 (page 42) shows what happens if Tom and Nancy specialize in what they do best and trade with each other. a) Tom produces 4000 discs and Nancy produces 4000 cases. b) If Tom and Nancy exchange cases and discs at one case per disc (one disc per case) they exchange along the Trade line and end up with 2000 CD units each—double what they can achieve without specialization and trade. 2. Nations can gain from specialization and trade, just like Tom and Nancy can. C. Absolute Advantage 1. A person (or nation) has an absolute advantage if that person (or nation) can produce more goods with a given amount of resources than another person (or nation) can. 2. Because the gains from trade arise from comparative advantage, people can gain from trade in they also have an absolute advantage. E. Dynamic Comparative Advantage 1. Learning-by-doing occurs when a person (or nation) specializes and by repeatedly producing a particular good or service becomes more productive in that activity and lowers its opportunity cost of producing that good over time. 2. Dynamic comparative advantage occurs when a person (or nation) gains a comparative advantage from learning-by-doing. V. The Market Economy A. Property Rights and Markets Trade is organized using two key social institutions: 1. Property rights, which are the social arrangements that govern ownership, use, and disposal of resources, goods or services; and 2. Markets, which are any arrangement that enables buyers and sellers to get information and do business with each other. B. Circular Flows in the Market Economy 1. A circular flow diagram, like Figure 2.10 (page 45), illustrates how households and firms interact in the market economy. 2. It reflects the circular flow of goods and services and factors of production in one direction, and the flow of money in the opposite direction. C. Prices coordinate decisions in markets.